Schwab’s business legacy is renowned

Published 5:00 am Sunday, May 20, 2007

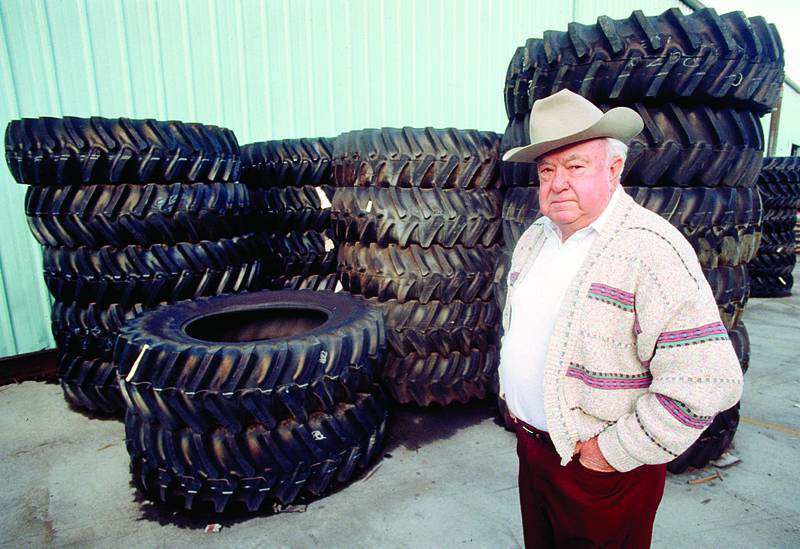

- Industry analysts say tire dealers won't be largely affected by the death of Les Schwab, shown here in 1995. But his reputation was well known around the nation - when he was more involved in the business that bears his name, dealers often would visit his office in Prineville seeking his advice.

The death of Central Oregon legend Les Schwab on Friday may symbolize the end of an era for Prineville and Les Schwab Tire Centers, but tire-industry experts say the legacy Schwab built should remain strong – as long as the new leaders do not stray too far from Schwab’s business philosophy that resisted Wall Street interests and bureaucracy.

”Certainly, there are signs that the company can keep it business-as-usual,” said Bob Ulrich, editor of Modern Tire Dealer, based in Akron, Ohio, which honored Schwab as the national Dealer of the Year in 2000. ”But there are still question marks.”

Trending

In more than 50 years, Schwab built his small Prineville tire company from almost nothing into a family-owned empire that made $1.6 billion in sales last year and has more than 7,000 employees – 1,500 in Central Oregon – and 400 locations throughout the West. In the last year of Schwab’s life, however, the company faced ongoing sexual harassment and discrimination lawsuits and a corporate shakeup.

Prineville, up to a certain point in time, was known as a cattle town, said John Shelk, the managing director for Ochoco Lumber Co. Next, it was known as a timber town as the various mills were the primary employers and as the mills were forced out of business. And then it became a home of Les Schwab. That is how Prineville has come to be defined, as the home of Les Schwab.

Prineville, a city of 9,990, soon will lose the hub of the company. Late last year, Les Schwab Tire Centers announced that it would uproot its headquarters from Prine-ville to Bends Juniper Ridge Development a 1,500-acre parcel that city officials hope will become an educational, industrial and research development park. Construction on the companys new 120,000-square-foot office, which will employ 350 people, is expected to begin soon. Completion is slated for fall 2008.

For years, rumors have spread throughout the Prineville community regarding Les Schwab Tire Centers future in Central Oregon, Crook County Judge Scott Cooper said.

I think theres been at least eight years Ive been hearing talk about them moving headquarters somewhere else, Cooper said. It was almost a relief when they finally picked Bend, because there was a lot of anxiety, a lot of people were worried theyd have to uproot themselves.

Now, many Central Oregonians feel the issue has settled, Cooper said. But some in the tire industry speculate that major changes could be on the horizon.

Trending

‘What do the grandkids want?’

The tire industry, nationally, won’t be largely affected by Schwab’s death, experts say.

”Les Schwab built a very strong organization and has strong leadership,” Richard Nordness, executive director for the Northwest Tire Dealers Association in Kennewick, Wash., said in a previous interview.

”I don’t think that organization will fall apart without him, because he has structured it as such,” Nordness said.

When Schwab was alive, his reputation preceded him – other tire dealers often visited his Prineville office, seeking his wisdom, Ulrich said.

”Arguably, Les’ operation was the most respected in the nation,” Ulrich said. ”It was because of the way he ran it, the customer service aspect. Even though it was a large national chain, dealers across the nation knew who he was and respected him.”

Joe Perry, an executive with America’s Tire/Discount Tire Co., echoed Ulrich’s sentiment when his competing business announced last fall it was opening in Bend.

”Les Schwab does a great job selling tires,” Perry said. ”He’s grown a great business over the years. I admire the business they do.”

As Schwab’s health deteriorated in the last few years, Ulrich said, industry experts have wondered how his legacy would move on. Schwab outlived his two children: Harlan, who died in 1971, and Margaret, who died in 2005. Schwab is survived by his wife, Dorothy, four grandchildren and several great-grandchildren.

Schwab had begun transferring ownership of the company to his grandchildren in the 1970s, according to his autobiography. Schwab transferred day-to-day operations to Chairman Phil Wick in 1983, after he suffered a heart attack.

The company said in the news release announcing Schwab’s death that his family members – most notably Schwab’s grandchildren – will own the company. But the release did not say if, or to what extent, they will be involved.

”The question will be, what do the grandkids want?” Ulrich said. ”Will they get involved? Will they let Dick (Borgman) run it for them? Will they try to cash out? I don’t want to sound cryptic, but I want to be honest: I think there’s a possibility that the business could be sold.”

Wick has recently announced he would reduce his work schedule, effectively easing himself out of the pilot seat. In December, the company announced that 17-year veteran Dick Borgman was replacing Schwab as chief executive officer of the company. Borgman had been president of the Les Schwab Holding Company Division.

Borgman did not return calls for comment Saturday. Wick declined to comment Saturday, saying that while the family is in mourning, no one from the company would comment.

Schwab was many things, Ulrich said, but he was not a sellout. Schwab could have sold his business many times to various competitors and investors, he added, but always refused.

”I could see a lot of investors wanting to invest in the company (now that Schwab has died),” Ulrich speculated. ”We’re not seeing a big impact industry-wise, although the dominoes could fall if they end up selling the business.”

If Les Schwab Tire Centers’ executives sell the company, the regional impact could be huge, Ulrich said, adding that the tire industry is sitting back, wondering what will happen to ”Les Schwab country.” The company is the second-largest private employer in Central Oregon.

”Les was one of a kind,” Ulrich said. ”He did things his own way and stuck to his values – something they don’t do in this day and age.”

The house that Les built

Les Schwab Tire Centers’ advertising focuses on Schwab’s emphasis on customer satisfaction – commercials showed energetic employees rushing to greet customers in their cars. Internally, Schwab emphasized his commitment to human relations. Schwab was one of the first Central Oregon employers to offer employee benefits like profit sharing and retirement accounts, according to the company. Schwab also offered funding for education, health and dental care and annual dividends. Through his benefits, employees get 50 percent of the company profits, the release said.

Those employee benefits helped make Schwab a legend in the tire industry, Nordness said.

”The way he brought tire-store managers up in the industry, within the company, made it very strong and very stable,” Norndess said. A number of those long-time employees are now running the company.

In Les Schwab’s self-published book, ”Les Schwab, Pride in Performance: Keep It Going!” he wrote that through his Profit Sharing Retirement Trust, ”any man can go to work for us at 23-24 years of age and have $1,000,000 in his Trust at age 60-65.” The benefits can be even better if the employee works up through assistant manager and manager positions.

”I think that a man joining our company has such a great opportunity I almost cry anytime I see or hear of anyone getting fired for dishonesty,” Schwab wrote. ”I can’t remember one single man leaving our company and doing better outside.”

Schwab also was known for promoting from within, moving loyal workers up the company’s corporate ladder. His book describes his philosophy to ”keep decision-making lower” on the corporate ladder.

”Let the people at the store level and your manager know you are behind them,” Schwab wrote. ”They are the ones who make you successful, not the person in a nice office who has nothing to do today but to send out another damn directive.”

Some employees, however, have complained that Les Schwab Tire Centers is a ”good old boys’ network,” denying women many of the advancement opportunities available to men.

In November, Les Schwab Tire Centers was hit with its fifth case in seven years alleging it violated an employee’s civil rights when Bend Les Schwab employee Teia Erickson filed a sexual discrimination complaint against the company. Erickson’s Oregon Bureau of Labor and Industries complaint alleged that her employers subjected her to sexually hostile working conditions because of her gender. Erickson worked at the Les Schwab store on South U.S. Highway 97 from April 1, 2006 to June 15, 2006, when Erickson said her supervisors laid her off because business was slow.

In January 2006, two Washington state Les Schwab employees filed a class-action sexual harassment lawsuit against the company, alleging Les Schwab has historically denied women promotion, training and other employment opportunities because of their sex. Four months after that, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission filed a lawsuit against Les Schwab on behalf of the women.

Les Schwab representatives have declined to comment on the lawsuits, saying the company does not comment on pending investigations. Representatives did, however, issue a written statement at the time regarding the EEOC lawsuit.

”We disagree with the EEOC and are disappointed it has reached this stage,” said the June 2006 statement. ”We have fully cooperated with the agency to date and while we continue to hope this can be resolved, we will vigorously defend our position, if necessary. We are committed to equal opportunity practices in all aspects of our business.”