How many chips in a serving? It could change

Published 4:00 am Saturday, February 6, 2010

- How many chips in a serving? It could change

Seeking a new weapon in the fight against obesity, the Food and Drug Administration wants manufacturers to post nutritional information, including calories, on the front of food packages.

The goal is to give people a jolt of reality. But the message could be muted by a long-standing problem: Official serving sizes for many packaged foods are just too small. And that means the calorie counts that go with them are often misleading. So to get ready for front-of-package nutrition labeling, the FDA is now looking at bringing serving sizes for many snack foods into line with how Americans really eat.

Combined with more prominent labeling, the result could be a greater sense of public caution about unhealthy foods.

“If you put on a meaningful portion size, it would scare a lot of people,” said Barry Popkin, a nutrition professor at the University of North Carolina. “They would see, ‘I’m going to get 300 calories from that, or 500 calories.’”

The problem is important because the standard serving size shown on a package determines all the other nutritional values on the label, including calorie counts. If the serving size is smaller than what people really eat, unless they study the label carefully they may think they are getting fewer calories or other nutrients than they are.

Seeking clarity

And if manufacturers increasingly push key nutrition facts to the front of packages — as many have already begun doing — the confusion could be magnified. Rather than helping fight obesity, it may simply add to the perplexity over what makes a healthy diet.

“If people don’t understand the serving, whatever number they get for fat or calories is misleading,” said William Hubbard, a former FDA official who consulted with the agency last year.

Consider the humble chip: most potato or corn chip bags today show a 1-ounce serving size, containing a tolerable 150 calories, or thereabouts. But only the most disciplined snacker will stop at an ounce. For some brands, like Tostitos Hint of Lime, that can be just six chips.

In the real world, many people might eat two or three times that, or more. Munch half a bag of Tostitos while watching the Super Bowl and you could take in about half the 2,000 calories an average person needs in a day.

“We are actively looking at serving size and evaluating what steps we need to take,” said Barbara Schneeman, director of the FDA office that oversees nutrition labels. “Ultimately, the purpose of nutrition labeling is to help consumers make healthier choices, make improvements in their diet, and we want to make sure we achieve that goal.”

Buyers in a rush

The push to re-evaluate serving size comes as the FDA is considering ways to better convey nutrition facts to hurried consumers, in particular by posting key information on the front of packages. Officials say such labeling will be voluntary, but the agency may set rules to prevent companies from highlighting the good things about their products, like a lack of trans fats, while ignoring the bad, like a surfeit of unhealthy saturated fats.

On today’s food packages, many of the serving sizes puzzle even the experts.

For ice cream, the serving size is half a cup. For packaged muffins, it is often half a muffin. For cookies it is generally 1 ounce, equal to two Double Stuf Oreos. For most children’s breakfast cereals, a serving is three-quarters of a cup.

It is difficult to say exactly how much people eat, said Lisa Young, an adjunct professor of nutrition at New York University, but she said that research showed that the portions Americans serve themselves had been growing in recent years.

When it comes to cereal, she said, many children probably eat two cups or more.

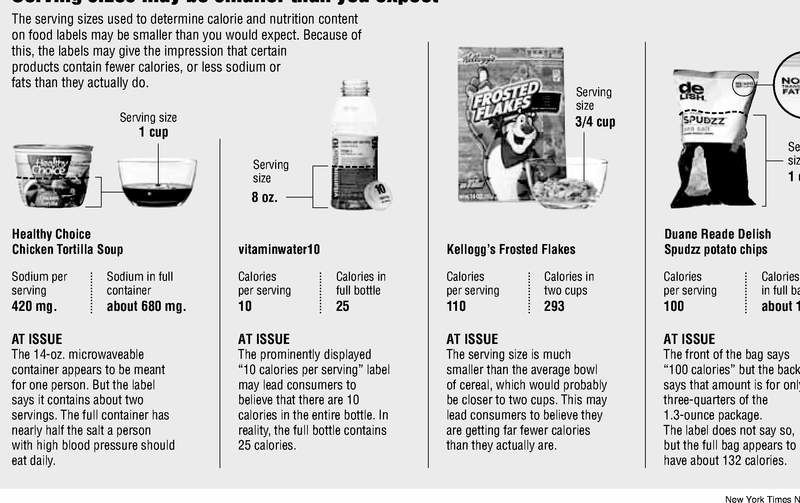

Parents who glance at a box of Frosted Flakes and see that it contains 110 calories per serving may not realize that their children may be getting several times that amount each morning at breakfast.

“To consumers, the serving size appears to be inconsistent and unintuitive,” said Wendy Reinhardt Kapsak, senior director of health and wellness at the International Food Information Council Foundation. “They have trouble trusting it.”

They may also have trouble seeing it, where it usually appears in small type in the Nutrition Facts panel on food packages. In surveys conducted by the foundation, many more people say they look at the calorie number than at the serving size on which it is based.

Standard serving sizes were created by the FDA in the early 1990s, partly to make it easier to compare the nutritional values of different products. Congress required that the serving sizes match what people actually ate. To determine that, the FDA evaluated data from surveys of Americans’ eating habits taken in the 1970s and 1980s.

Some nutritionists say those surveys may be suspect, because people typically underestimate how much they eat. And there is general agreement that they are out of date.

The FDA has vowed to re-evaluate serving sizes before. Amid concern over obesity, it said in 2005 that it was considering changes. That effort languished, but has now been revived by the Obama administration.

No easy answer

Still, the solution is not as simple as merely bumping up the standard portions for some foods. Officials worry that could send the wrong message. If the serving size for cookies rose to 2 ounces, from one ounce, for instance, some consumers might think the government was telling them it was fine to eat more.

A trip to the store shows how a smaller serving size can affect health or nutrient claims in ways that may confuse consumers.

Duane Reade, the pharmacy chain, sells 1.3-ounce bags of its Delish potato chips with the words “100 calories” in bold type across the front. But the calorie count refers to a 1-ounce serving, and the label says the bag holds one-and-one-third servings. That appears to conflict with FDA rules that require packages of that type to be labeled as a single serving. Doing the math, the full bag would appear to contain around 130 calories.

After being questioned about the bags by The New York Times, Duane Reade said it would correct the chip labels.

‘Heart Healthy’?

While in some cases companies have leeway in how they label smaller packages, in 2004 the FDA urged manufacturers to label them as single-serving containers. The agency was interested primarily in making calorie counts clearer, but other food ingredients, like salt, also raise concerns.

Healthy Choice soups, made by ConAgra Foods, are sold in 14-ounce microwaveable bowls. Although they appear to be meant for one person, the label says they contain “about two servings.”

Many of the soups are billed as “Heart Healthy” and claim to have a reasonable amount of salt per serving. But a shopper has to examine the label closely to understand that the salt claim refers to half a bowl. A full bowl may contain close to half the daily salt allowance recommended for many people.

Michael Jacobson, executive director of the Center for Science in the Public Interest, a consumer advocacy group, called such labeling disingenuous.

A ConAgra spokeswoman, Teresa Paulsen, said the Healthy Choice bowls contained more than one and a half times the FDA-established standard serving for soup, which is about eight fluid ounces, or one cup. Because of that, she said, “we think it makes sense to label the package as two servings.”