A geothermal first in Oregon

Published 5:00 am Monday, March 21, 2011

- A geothermal first in Oregon

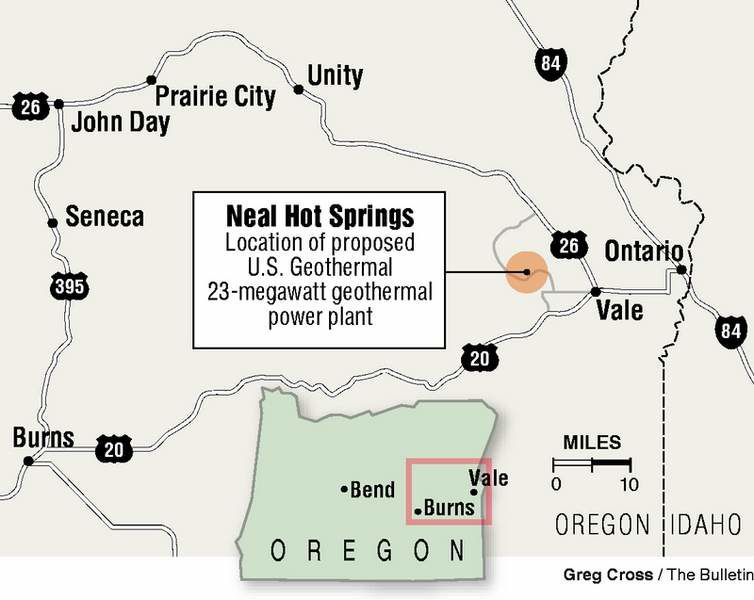

While drilling for minerals near Neal Hot Springs west of Vale in the late 1970s, a crew hit a geothermal reservoir, creating a 100-foot geyser that spewed for about a month before collapsing.

“They got a surprise,” said Daniel Kunz, president and CEO of U.S. Geothermal Inc., referring to the drilling crew.

Unfortunately, the technology did not exist at the time to turn that geothermal energy into power.

But it does now, and Kunz’s company plans to deploy it to build Oregon’s first utility-scale geothermal plant, financed, in part, by a $96.8 million federal loan guarantee and employing the latest technology.

It’s the first such loan in the nation offered to a geothermal project and will cover about 75 percent of the project costs, which were estimated at about $129 million as of Dec. 31.

“It’s really going to be one of the cutting-edge, or leading-edge, geothermal power plants in the nation,” Kunz said.

The project also drew bipartisan raves from Oregon’s congressional delegation when the loan closed last month.

In various news releases, U.S. Rep. Greg Walden, the Hood River Republican whose district includes the plant, along with the state’s two Democratic U.S. senators, Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley, all praised the jobs the plant would bring and its nearly emission-free operation.

The Neal Hot Springs plant will employ about 15 workers long term, Kunz said, and about 150 during construction, which technically began when the company began drilling production wells in 2008.

Construction of the plant should begin in about a month, as soon as U.S. Geothermal receives the OK from the federal government.

“We’re just that close,” he said.

TAS, a Houston company, will build the plant’s three modules in its Texas factory, and truck the sections to Oregon for installation. Each module will be a single 7.33- megawatt power plant. Engineers designed the modules to fit on a truck and meet size limits to avoid having to shut down highways during transport.

U.S. Geothermal, based in Boise, Idaho, has hired a contractor from Ontario for some of the concrete work at the site, Kunz said.

The Neal Hot Springs plant will be the first in Oregon to generate electricity for sale to a utility, although direct use of geothermal energy to heat homes and swimming pools has been around for more than a century.

In fact, the first large-scale use of energy from a hot springs began in 1864 with the construction of the Hot Lake Hotel near La Grande, according to the U.S. Department of Energy.

U.S. Geothermal expects the Neal Hot Springs plant to generate 23 megawatts annually, or enough to power about 23,000 homes, Kunz said. It’s projected to begin operation late next year.

An efficient plant

Idaho Power, which serves Ontario, Vale, Jordan Valley and other pockets of Eastern Oregon, along with much of southern Idaho, has a 25-year agreement to buy all the electricity.

While the utility’s cost per megawatt-hour fluctuates over the life of the agreement, the rate will generate about $22.5 million in annual revenue when calculated equally over 25 years.

Those revenues, Kunz said, will pay off the government loan, along with the investors’ stakes and royalties to landowners.

With geothermal power, much of the costs come at the front end of the project from drilling, exploration and construction. Once built, the fuel for the plant comes out of the earth.

Neal Hot Springs will actually cost Idaho Power less per megawatt-hour than electricity generated by a new natural gas plant, Kunz said, due to the volatility of natural gas prices.

Built with the latest technology, the Eastern Oregon power plant is expected to be about 15 percent more efficient than existing geothermal operations. It also could serve as a template for other large-scale geothermal electricity projects in the state, he said.

All geothermal power plants produce electricity using steam or vapor to turn a turbine that activates a generator, which produces electricity, according to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

Most draw steam and water, at temperatures higher than 360 degrees, from reservoirs miles below the earth’s surface. In these flash systems, the steam gets separated from the water and turns the turbine. Any water, along with the condensed steam, gets injected back into the earth, according to the energy lab.

Neal Hot Springs will have a binary-cycle plant, which works with lower-temperature water — between 225 and 360 degrees — a secondary fluid and a heat exchanger in a closed-loop system, according to the energy lab and the National Geothermal Association.

The water drawn from below ground boils the secondary fluid, which gets vaporized in the heat exchanger to turn the turbine. The water and secondary fluid never mix, and each gets recycled, with the water sent back underground via injection wells.

Neal Hot Springs also will rely on air-cooling, rather than water, Kunz said, which will eliminate any steam or vapor plume rising from the plant and marring the view.

“If you look at it from afar,” he said, “you won’t even know it’s operating.”

Located on about 10 acres, the plant will be about the size of a two-story building, he said, and painted to blend in with the surrounding area.

Because binary-cycle plants generate electricity with lower-temperature water, they might help generate electricity at other sites around the state.

“There’s huge potential for binary-cycle plants in Oregon,” Kunz said.