Dial-A-Ride’s patrons often get busy signal

Published 4:00 am Sunday, February 19, 2006

- Dial-A-Ride's patrons often get busy signal

After four weeks of trying to use Dial-A-Ride, Allyson Griffith gave up her job. The bus service, she said, was too sporadic.

The 18-year-old, who is part of the Cascade Youth and Family Center’s teen housing program, needed the city’s on-demand bus service to get to and from work. With no car of her own or parents to drive her, Griffith’s only option to get from Bend’s west side to her job as a pricer at Grocery Outlet on the east side was public transportation.

But the service would show up an hour early or an hour late. She would have to call two weeks ahead to schedule rides, and even then Dial-A-Ride could only pick her up about 50 percent of the time.

When she didn’t get a ride, Griffith would walk the 2 1/2 miles to work or pay the $10 one-way cab fare.

”I quit my job because of Dial-A-Ride,” Griffith said.

She and other teens and young adults at the teen housing program have had trouble using Dial-A-Ride for getting to work, school or medical appointments.

Jodi Hammack, coordinator for the housing program, said the demand points to the need for a fixed-route, public transit system in Bend that people can rely on.

”When they try to get rides, it seems to be full,” Hammack said of the teens. ”It’s being used so much, (Dial-A-Ride) isn’t big enough for what the community needs.”

The teens are not alone. Seniors and those with disabilities also report trouble getting rides for doctor appointments, lunch dates and meeting times, even when they are requested days in advance.

No room on the bus

The cry for more public transit is not anything new for the city of Bend, which is the largest city in Oregon not to have a mass transit system.

Dial-A-Ride in Bend began in the mid-1970s under the direction of the United Senior Citizens of Bend with the focus on transporting seniors. That organization handed over the operations of the service to the city in 1989.

For more than a decade, the city operated Dial-A-Ride as a transportation service for just seniors and those with disabilities. Then in 2002, the city opened the service to the general public, which doubled the amount of funding the city could get to support the service.

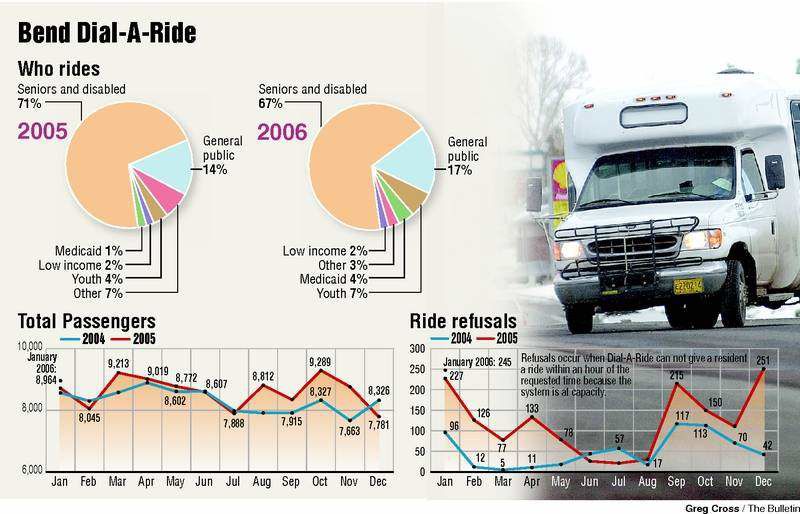

Since 2002, the total passengers Dial-A-Ride transports has increased by 12 percent with the annual total in 2005 at 103,500 passengers.

Data shows that from 2004 to 2005, the number of times Dial-A-Ride has not been able to give a resident a ride within one hour of the requested time has more than doubled. In 2004, the total refusals were 602. For 2005, it was 1,444.

City Assistant Public Works Director Brad Emerson said city staff is aware of the increase in demand and Dial-A-Ride’s inability to meet it.

”We just know we haven’t been able to provide (for the increase in demand). We don’t want to have to turn people away,” Emerson said. ”Our goal is to be able to provide services for everyone.”

”It is definitely harder to get a ride,” said Kathy Ostrom, who is the project manager for Paratransit Services, LLC, the company the city contracts with to operate Dial-A-Ride.

However, she also noted the number of times Dial-A-Ride can not give a resident a ride within an hour of the requested time – known as the refusal rate – are 1 percent to 3 percent of the total trips the service makes. Refusal rates are an indication of when the system is at capacity.

The city has a goal to have the refusal rate at or below 1 percent of total rides given – a goal Dial-A-Ride has historically met. The city also is obligated under the Americans with Disabilities Act to have a refusal rate of less than 2 percent.

Since September, most months have had refusals rates between 2 percent and 3 percent.

”We are really working hard to fix that,” Ostrom said. Dial-A-Ride is looking at the times of day most refusals are made and trying to reschedule drivers and routes to meet the demand. But Ostrom noted while early morning and afternoon hours tend to have the highest refusal rates, the times are more spread out than they used to be.

”We are looking at everything we can do to adjust that,” she said.

Part of the problem, Ostrom said, is having the demand for Dial-A-Ride increase and the amount of hours it is allowed to operate stay the same.

Dial-A-Ride operates on a first-come, first-served basis and riders have to call 24 hours in advance to schedule their pick-up and drop-off times. Passengers who are seniors, have disabilities or qualify as low income pay 75 cents. The general public pays $1.25.

The city has 25 buses, of which 17 to 18 operate at peak hours. Dial-A-Ride also hires 25 drivers, 12 of which are full-time employees.

More than two-thirds of Dial-A-Ride users are seniors or those with disabilities, Emerson said.

In September, the number of students using Dial-A-Ride jumped. Ostrom said of the average 400 riders the service transports a day, 40 are students. Many of the students need transportation because they go to schools outside of their district.

Dial-A-Ride’s busiest times are from 7 to 9 a.m. and from 2 to 4 p.m, which stems from the start and end of the school and work day.

As the number of users has increased, the money going to Dial-A-Ride has not.

City Councilor Jim Clinton does not see the council spending more money on Dial-A-Ride anytime soon because the city budget is already stretched thin.

”I am sure a lot of people would love to (increase funding), if we had it. But we’re not going to get rid of a fire crew or decrease the number of police officers in order to pay for it,” Clinton said.

Because the service is so heavily subsidized by the city, increased ticket sales for Dial-A-Ride does little to cover the cost of added demand. In 2005, the city figured it recovered just 7.5 percent of the total cost to transport residents. The city estimated it spent an average of $13.84 on every trip.

The city has set a limit on how many hours it can operate per year, so Dial-A-Ride cannot add more buses and drivers when the demand goes up.

Ostrom said the refusal rate is not so high that Dial-A-Ride would ask council for more money to fund the program. This fall, the service did get a boost when a state grant allowed Dial-A-Ride to add 100 hours of operation.

Clinton hopes to see a fixed-route transit system in place sometime in the next six months, which would help ease the demand on Dial-A-Ride.

”Not only would the city go ahead with some fixed-route transit system of some type, which is still under study, they would look at Dial-A-Ride to see if there is a way to make it more efficient,” he said.

That could mean looking at if Dial-A-Ride is using the right kind of buses and if the general public using the system should have to pay more.

”There’s a continuing question of if it is as efficiently run as it could be,” Clinton said.

Waiting for the bus

Dan Norris, a 53-year-old man who has used Dial-A-Ride for the past five years, is among those who say it has been harder to get rides.

Norris has multiple sclerosis and has used a wheelchair for more than five years. In January, he called almost two weeks in advance to get a ride to a meeting with a group that advocates for those with disabilities and access issues. Despite the advanced notice, Norris said the best Dial-A-Ride could do was drop him off an hour before the meeting and pick him up 45 minutes after it was finished.

He sees the increase in demand for Dial-A-Ride from two sources – more use from the general public and more permanent riders on board.

But not everyone has problems with the bus service. Eva Burney, a permanent rider who volunteers at the Bend Senior Center three days a week, said the service is reliable.

Norris, who was once a permanent rider while working at the U.S. Forest Service, also said he had steady bus trips when he went to work.

But the increasing demand for Dial-A-Ride means it is harder to be classified as a permanent rider, where the rider has a set schedule and doesn’t have to call in advance.

Ostrom said Dial-A-Ride has a goal of having no more than 50 percent of its ridership at one hour be permanent riders.

Like the rest of the service, becoming a permanent rider is first-come, first-served. When Griffith was working at Grocery Outlet, she tried to become a permanent rider, but Dial-A-Ride said it already had too many people scheduled.

”I worked 12 to 5 Tuesday through Friday, and I still couldn’t get a permanent schedule,” she said.

Not everyone must wait to become a permanent rider.

”We see if we can accommodate that time of day. Normally it just depends on the time of day,” Ostrom said.

A fixed-route system

Ostrom – and others – acknowledge that the flexibility needed to use Dial-A-Ride doesn’t always suit workers.

Sue Smit, who is with the Central Oregon Partnership and works with low-income residents, said the working poor are struggling to get by as they juggle the cost of housing and transportation in Bend. She also said that for many Dial-A-Ride’s policy that it could come 10 minutes before or after the requested time doesn’t mesh with their schedules.

”It doesn’t work for someone who is trying to be at work on time. The existing system really isn’t something for a low-income working individual,” she said.

Smit, who has been working on transportation issues for five years, said she believes the city is making progress in providing a fixed-route system.

”I think we are a little closer in doing that. We will see some pilot projects in the fall,” Smit said.

This past fall, city staff presented to the council a plan for a fixed-route system that would scale back Dial-A-Ride and add bus routes that would run on a regular schedule.

As proposed, the routes would link the college, downtown, shopping districts and the hospital. The Dial-A-Ride program would still be available for seniors and those with disabilities. The fixed-route system would operate Monday through Friday from 6:30 to 9:30 a.m. and from 3:30 to 6:30 p.m.

Emerson said the proposal is being reviewed by public transportation consultants now. He expects the plan to come back before the council’s transportation subcommittee in March and the council as a whole in April.

Clinton said he would be disappointed if he didn’t see some version of a fixed-route bus system in place by this summer.

”(Dial-A-Ride) has become something like a taxi service, a low-cost taxi service you have to reserve 24 hours in advance,” Clinton said. ”It’s part of the transportation picture, but it’s not the whole picture. It doesn’t serve the whole need.”

But as the city plans for a fixed-route system, some worry of what will become of Dial-A-Ride, which is needed for seniors and those with disabilities.

”I absolutely believe we need a fixed-route system,” Smit said. ”My concern is that we don’t cut or limit services to seniors and the disabled population as we build a fixed-route system. And that is going to be difficult.”

A fixed-route system could be hard for seniors to use, said Virginia Reddick, who is the vice president of the United Senior Citizens of Bend.

”These people can’t walk to the stop. They are picked up at homes. I just told them I don’t want anything happening to Dial-A-Ride going to the senior center,” she said.

Grandfathered when the city took over Dial-A-Ride, trips by seniors to the senior center have always been free for those coming to eat meals. Dial-A-Ride makes about 500 trips a month to the center so seniors can eat, play bingo and even dance.

Reddick said she wants to make sure that rides remain free, even if the service changes.

”These people live so close to the dollar. If they had to pay they couldn’t come,” she said.

LaDean Eicker, who is physically disabled and uses a wheelchair, runs the bingo program at the senior center and said without Dial-A-Ride she couldn’t go.

”I don’t know what I would do without Dial-A-Ride, there’s no way I could come to work,” Eicker said.

Both Emerson and Ostrom said Dial-A-Ride would remain in place, but do not know what changes, if any, would be made once a fixed-route system was operating.

Emerson said they city is still looking at ways to fund a fixed-route system, but said no more money would be taken out of the city’s general fund.

One option would be to increase Dial-A-Ride fares. Another option would be to work with large employers and institutions on providing passes for a fixed-route system.

”We want to provide as much service as we can with the funds available,” Emerson said.