GOP sees shot at change

Published 5:00 am Sunday, April 23, 2006

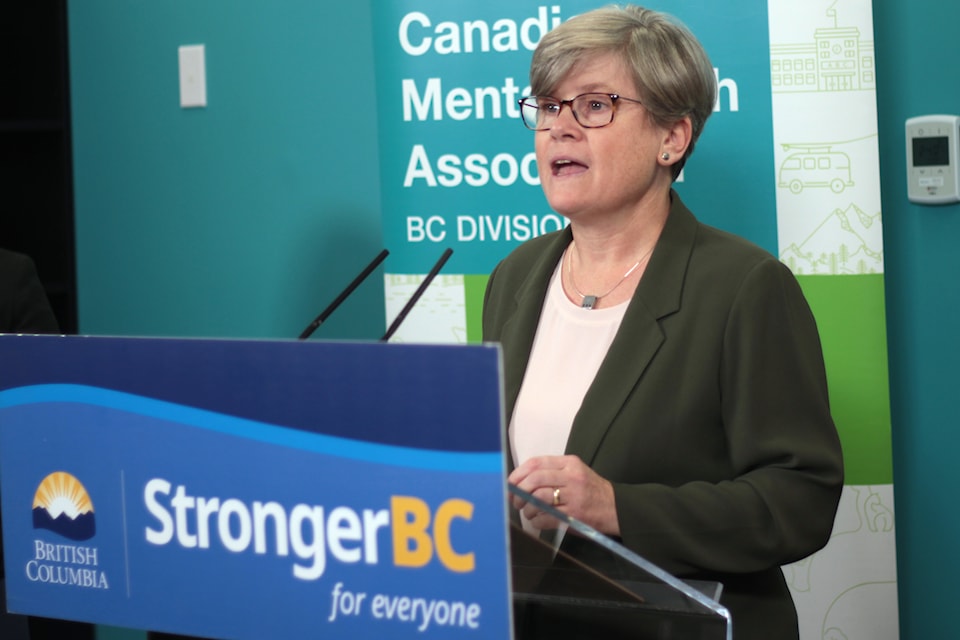

- Kevin Mannix

SALEM – The last time Oregon had a Republican governor, the Berlin Wall was still standing, the timber industry was still king, the city of Bend was less than half its current size and nobody had ever heard of the World Wide Web.

Voters have elected four Democrats – one of them twice – in the two decades since Republican Gov. Vic Atiyeh left the center office at the Capitol in 1986.

But the political winds are changing this year, predict the three high-profile Republican candidates who hope to unseat Gov. Ted Kulongoski – whose approval ratings are in the cellar and is facing a primary challenge from within his party.

”Most of the electorate is disillusioned with government and people are more willing to talk about change,” said Ron Saxton, a Portland attorney and former Portland School Board chairman who made the reform of the state’s public pension system a front-burner issue four years ago.

The field of candidates for the Republican bid is led by Saxton and Kevin Mannix, the Salem attorney and former Oregon Republican Party chairman who won the Republican primary in 2002, but narrowly lost to Kulongoski in the general election.

”There’s a transition going on in Oregon,” Mannix said, pointing to voter-approved tax limitations, the 2004 ban on same-sex marriage and the Measure 37 property rights law as evidence that the public sees more eye-to-eye with Republicans today.

The winner of the Democratic and Republican nominations in the May 16 primary will face each other on the November ballot, which also looks likely to include a potential wild card in state Sen. Ben Westlund, a former Republican who has filed to run as an independent.

Mannix and Saxton too are joined in the May 16 primary by state Sen. Jason Atkinson, R-Central Point, an ambitious Southern Oregon legislator and former professional skier and bicycle racer who is making his first bid for statewide office.

Saxton placed third in the 2002 primary. Mannix, who was seen as more socially conservative, won the nomination despite spending less money.

Both have refocused their campaign strategies this year, with Saxton stressing themes to help burnish his conservative credentials – such as signing the ”no new tax pledge” offered by Grover Norquist’s Americans for Tax Reform – and touting himself as a political outsider.

”People don’t have confidence that their tax dollars are being spent well,” Saxton said.

Saxton said he hasn’t changed his tune from four years ago – when he was widely seen as a moderate – but political observers and former supporters disagree with that assessment.

”I reregistered four years ago to Republican so I could vote for him, but I would not do the same thing today because of the way he’s messaging and marketing himself,” said Karla Wenzel, who served with Saxton on the Portland School Board and gives him high marks for his management style.

But this year, Wenzel is supporting Westlund, she said.

Mannix, meanwhile, has softened his approach from his previously punchy style, which he acknowledges might have turned off swing voters in 2002.

”I learned on the general election trail that it is important to be reaching out to folks through the entire process,” he said. ”You need to fight for the Republican base in the primary, but you also need to win over votes from Democrats and independents and I have been doing that this time.”

Serious contenders

Pundits say the race will likely come down to the better-known Mannix and Saxton – and that Atkinson is ably positioning himself as a serious contender for a future contest.

”He’s raised little money, but I think his campaign is getting people talking,” said veteran Republican campaign strategist Chuck Adams of Salem. ”He is a young guy laying the groundwork.”

Atkinson dismisses such talk, however, and even threatened to not grant an interview if this story suggested he is just a political rising star.

”Nobody in their right mind would work as hard as we are working just to play games,” he said.

Atkinson said Oregon is hopeful and ready for a new generation of leaders, and his internal polls show him winning the Republican nomination. He also has penned a 96-page book, ”What We Wished All Politicians Understood.”

”I don’t pay attention to the critics,” he said.

Mannix has already won a plum endorsement from Oregon Right to Life, the anti-abortion group, and that seems likely to resonate among the conservative voters that dominate Republican primaries.

But Atkinson also is a religious conservative and shares those anti-abortion views. He even has an unofficial Web site where people can offer prayers for his successful campaign.

Saxton does not support banning abortion but has talked frequently on the campaign trail about his willingness to limit access to teenagers through parental notification laws and to ban late-term abortions.

He has raised the most money of the three and will blanket the airwaves for the next month. He’s not squirreling away any money for the general election, he said.

Saxton has been endorsed by 14 legislators, Associated Oregon Loggers and Oregonians for Food and Shelter, a pesticide industry group.

Atkinson, meanwhile, has earned the endorsement of the Oregon Farm Bureau – a surprise for an organization that usually stays neutral in the Republican primary.

”Jason is a proven entity that has been a passionate advocate of the natural resources industry,” said farm bureau President Barry Bushue, in a release.

Mannix is being helped by an attack ad against Saxton that is being financed by his single-largest campaign supporter, medical equipment maker Loren Parks, who has given Mannix $371,000 for this year’s bid.

Mannix said he has nothing to do with that ad, however.

The script suggests that Saxton and disgraced former Gov. Neil Goldschmidt – who sexually abused a teenage girl in the 1970s – are close friends, when in fact they are not. It also points out that Saxton once gave a political donation to Kulongoski.

Saxton shrugs off the donation, which was given to Kulongoski in his bid for attorney general in 1992.

”I’ve given hundreds of contributions over the years, a few of them to Democrats,” he said. ”That’s part of heading up one of the biggest law firms in the state.”

Because of his limited funds, Mannix is running short commercials, at 15 seconds apiece.

”He can afford to run twice as many ads, but ours are twice as good,” Mannix said.

Mannix remains $350,000 in debt, with much of that from his 2002 campaign – a figure that raises eyebrows in a party that preaches fiscal conservatism.

But he said his loans aren’t due to be repaid until after the November election, and insists they aren’t a liability. He spent much of the past four years raising millions for the Republican Party instead of for himself, he said, and party members appreciate that.

Republican consultant Adams said if Mannix and Saxton had the same resources, Mannix would be the clear front-runner. But Saxton’s financial edge combined with questions about Mannix’s debt and his connections to medical equipment maker Parks make it a tossup, he said.

Political mistakes

The three candidates each say his individual leadership style makes him the best candidate to be governor and point to past accomplishments.

But the reviews of their personal histories are not universally congratulatory.

Mannix boasts of his tenure as a legislator, during which he was the most prolific bill-producer at the Capitol. In those days, he even earned a nickname, Amend-o-Mannix, for his willingness to tweak bills in an effort to gain support.

He started his career as a Democrat, but his social views were out-of-step with the party. He switched allegiances in the 1990s and was named vice chairman of the Republican Party in 1998.

He is the author of Oregon’s tough mandatory sentencing law, Measure 11, which passed on the 1994 ballot.

But an incident in 2003 soured several legislators on Mannix.

With the state facing a budget crisis, Mannix talked with lawmakers and said an income tax surcharge – modeled after one signed by Atiyeh in the 1980s – would be the least objectionable way to balance the budget and preserve state services.

But almost as soon as lawmakers passed that package, Mannix joined the campaign to oppose it. It was defeated by voters in Measure 30.

”In this business, your word becomes everything,” said state Sen. Jackie Winters, R-Salem, who voted for the surcharge. ”He said ‘This is the way to go,’ and the expectation was he would be out there with us.”

Mannix, 56, is married and has three children.

Atkinson describes himself as an independent thinker who was able to work across the aisle with Democrats during his time in the Legislature, but most lawmakers can’t cite many examples. He votes routinely with the minority conservative bloc in the Senate.

”He’s extremely conservative but is working hard in his campaign to try and deny that,” said Rep. Bob Jenson, R-Pendleton.

Bill Lunch, a political science professor at Oregon State University, said Atkinson is considered environmentally moderate because he has supported some conservation efforts and authored a plan to encourage litter cleanup along rivers.

”It is an interesting combination, to put together conservative views on social policy and moderate views on the environment,” Lunch said.

Atkinson is still not well-known in the Willamette Valley, where most of Oregon’s voters live, Lunch said.

Atkinson, 35, is married and has a young son. His family owns a Christian radio station.

Saxton is recalled as a rational and moderate member of the Portland School Board who was able to move an agenda and focus attention on the costs of health insurance and retirement benefits.

But he did not oversee any dramatic changes in those contracts while on the board.

”The entire board under the leadership of Ron was focusing on cost management,” said Debbie Goldberg Menashe, who served two years on the board when Saxton was chair. ”He was not able to implement any specific changes, but it was the beginning of the conversation.”

While not all of the board members saw eye-to-eye with Saxton, he earned the respect of all of them for his management style. ”Ron is an intelligent, calm and rational man,” Goldberg Menashe said.

A Democrat, Goldberg Menashe won’t rule out supporting Saxton in the fall if he advances to the general election.

Still, his tenure on the board also will be remembered for the hiring and then release of a high-profile superintendent, Ben Canada, who got a $250,000 buyout and helped fuel widespread criticism of how the state’s largest district spends money.

In his defense, Saxton said Canada was hailed as a brilliant hire when he arrived, and that things just didn’t work out.

Wenzel, who also served with Saxton on the board, said he was honest and direct. ”He was not a hide-the-ball kind of guy,” she said. ”His focus was guided by reason, which is interesting, seeing where he is now.”

Ann Nice, the president of the 4,000-member Portland Association of Teachers, said Saxton was seen as fair by teachers, even though there were disagreements and Saxton made it clear he wasn’t a big fan of unions.

Because of that history, Saxton’s positions on the campaign trail – such as his suggestion that public workers lose their pensions entirely in favor of a private sector-style 401(k) plan – have been a surprise, she said.

”He does not sound as worker-friendly as his practice had been in Portland,” she said.

Saxton, 51, is married and has one son.