Drawing for memory

Published 4:00 am Saturday, December 9, 2006

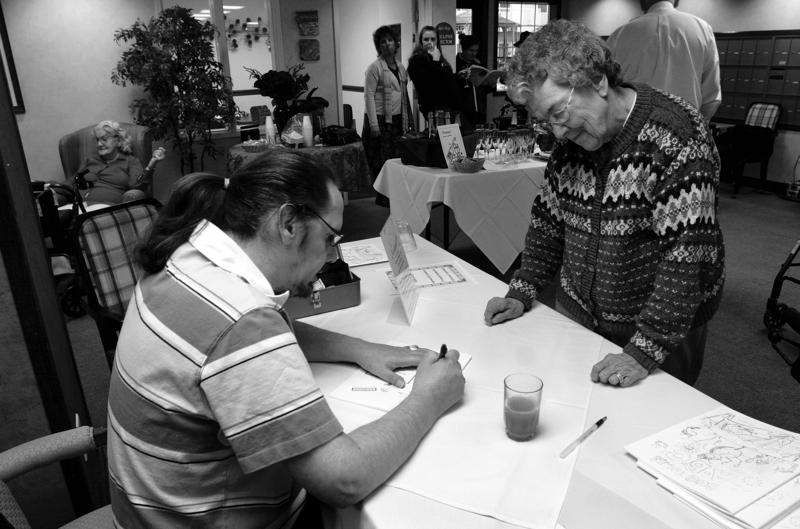

- Mike ”Felix” Kelly, 47, signs a copy of his coloring book, ”Bug Town A-B-C's,” for Cleo Cox at a Nov. 30 book signing at Aspen Ridge Retirement Community.

hadow boxes hang outside each of the rooms at Aspen Ridge Retirement Community’s 40-bed Memory Care facility.

Like scrapbooks distilling the residents’ lives, the glass-covered memory boxes are filled with photos, cards, drawings and ephemera from the lives of the residents, many of whom have Alzheimer’s disease. The boxes serve as signposts as to the location of their rooms.

The boxes also remind workers to be compassionate toward the residents: ”They can’t tell us their story anymore, so it helps the caregivers with compassion and understanding about the person,” said employee Adele Lavoie. ”They’re not just a shell of a person, you know? It really helps.”

In short, the boxes are an argument for dignity, showing what words alone can not convey: Here live people who laughed, loved and led productive lives. Who raised families. Who modeled for catalogs. Who fought in wars.

Who are still around.

But Mike ”Felix” Kelly’s shadow box tells a slightly different story. At 47, he is decades younger than his neighbors at Aspen Ridge’s Memory Care facility. And unlike most of them, Kelly does not have Alzheimer’s or age-related memory problems.

But Kelly, formerly of California, cannot form new memories or retain information for very long. In 2002, at age 43, he had a heart attack during which his brain was deprived of oxygen for an estimated seven to 10 minutes, say relatives who live in Bend.

In Kelly’s shadow box, there is a photo of him with his former heavy metal band, The Hungry Beast, and a flier for one of its concerts. Another photo shows Kelly standing shirtless and muscled on a mountaintop. Still another shows the former black belt wearing his karate gi (uniform) and doing a kick higher than his head.

Kelly’s flirtatious ways as a teenager earned him the nickname Felix, as in ”Felix the Cat,” and there’s a stained-glass Felix the Cat of his own making inside the shadow box.

Inside his room, an electric guitar rests on a stand next to a small amp. The walls are decorated with paintings Kelly did before his heart attack. They are other-worldly: rocks meld into floating ships and characters are embedded in the scenery. Stars appear to be born.

The heart attack happened while Kelly was onstage at a Simi Valley poetry reading. Though he no longer paints, he still draws.

His mother, Shirley Burg, 81, lives in a cottage of her own on the Aspen Ridge premises.

”In Simi Valley, he was with a group of people who were encouraging poetry. Every Friday night, they would meet at the back of this one store, and all these kids, up to the age of about 18, as young as about 12, would bring their poems.

”And he was reading his poem for that night when he collapsed in front of the kids. He used to recite poetry like mad.”

To Kelly, sitting across the table, she said, ”What’s your favorite poem?”

”I don’t know,” he replied.

”You don’t know now, huh?” she said. ”How about Edgar Allen Poe’s ‘The Raven’?”

”Oh, I know his stuff,” he said.

”He has short-term memory loss, and he lost about 20 years of his life,” she explained. ”He’s living in about 1981. If you ask him how old he is, he won’t know. But he knows what year he was born.”

Didn’t anybody at the poetry reading know CPR?

”Yeah, they were doing CPR, but they couldn’t stop his heart from beating so fast. By the time he got to the hospital, his heart was beating about 500 beats a minute. It was just flopping. The doctor explained to me, he said, ‘They kept oxygen in his lungs. They kept his heart going, but it didn’t go beyond his lungs. It didn’t go to his brain.’”

According to his mother, he was in a coma for three days, and the California hospital he was at was not well-equipped with heart machines. ”It took ’em two weeks to get him in for an angiogram, and he had two completely closed arteries.”

”And he was 43 then,” added Lavoie, sitting nearby.

”43?” Kelly asked, sounding shocked.

”Yeah,” Burg answered. ”How old are you now? How old are you today?”

Nothing.

”How old do you feel?”

”A hundred,” he replied.

But the sentiment lingered on his mind. A couple of minutes later, when his sister, Jessica Dickinson, arrived for the signing, Kelly asked, ”How old am I?”

”47” his mother and sister answered in near unison.

”Oh, Jesus,” he said, eliciting laughs around the table.

Coloring book

On the last day of November, across the street from the Memory Care building, Kelly took a seat at a table set up specially for the occasion: a book signing for his new coloring book, ”Bug Town A-B-C’s.”

Before his heart attack, Kelly began drawing it for a family friend.

”I was just bored one night, and I just started drawing,” he explained. He flipped it open and pointed to the ”M” page. ”Look at that guy. That’s a good monkey.”

According to his mother, Kelly started the book about five years ago when they lived in California.

According to Burg, ”He just came out and showed me this, and he said, ‘What do you think of that?’

”I said, ‘It’s cute; what are you going to do?’

”He said, ‘I’m going to make a coloring book for Madison,’” the family friend.

After moving to Aspen Ridge in July 2005, ”I got him to finish it up,” she said, ”the last five or six pages. And to get him to do it, you’d just sit him down and maybe he’d do one page, and maybe three days later he’d do another page. Finally got him through it, and since he has to live where he is protected, I thought, OK, turn the money in to Alzheimer’s (the Central Oregon Alzheimer’s Association). That’s where they’re going to help him.”

The books sell for $10 and are available at Aspen Ridge.

It’s a personal cause for Burg on another level: Her third husband, Dick Burg, had died from Alzheimer’s prior to Kelly’s heart attack.

Kelly’s sister explained that he lived in a trailer behind the Burgs’ home in Pacific Palisades. Kelly ”was like their handyman, and he helped mom with that aspect of it, and then after (Dick Burg) died, part of the estate required that the house be sold. She bought a place where she and Mike lived over in Simi Valley.”

Moving to Bend

Dickinson explained that Kelly’s heart attack had been the result of some kind of (arterial) blockage. ”It might have been cholesterol, but that wasn’t the way it was explained to us. They just said that he had a blockage. So I don’t know whether it was a clot or cholesterol or what it is.”

He now has a stent as a preventive against more heart trouble.

”The fact that he is alive is a miracle,” she said. She asked that we not print details of his institutional experiences in California. But the family was not happy with the care he was receiving, including the cocktail of pills his caregivers had him on.

”The part you can put in there: He was dying because of the treatment he was receiving at that place,” she said. ”We have a friend, Shannon Bart, who is the social worker/intake person for Harmony house,” referring to another health care center in Bend. ”She knocked on my door and said, ‘I came to talk to you about your brother.’”

”We got together with her and Dr. Paul Johnson,” a private practitioner in Bend, ”and Dr. Johnson accepted Mike as a patient, sight unseen, and arranged for him to be transferred up here, and undertook the treatment of him.”

Kelly was taken off the medications immediately after arriving in 2003.

”When he first came here, if you put soft food in his mouth, he didn’t know to chew it,” Dickinson said. ”And by the time 24 hours went by, he could sign his name.”

His mother followed to Bend soon after her son. In July 2005, he was transferred from Harmony Health Care Nursing Center to Aspen Ridge, where his mother was living. ”He’s not the normal patient for her,” Dickinson said, ”but because Mom was here, and John (Aspen Ridge Executive Director John Bragg) accepted Mike without seeing him, based on Mom being here and based on my description of what his needs are.”

It was Burg who lobbied Aspen Ridge’s management to help publish the coloring book, which features short phrases or poems with each of Kelly’s illustrations: ”Vernon the viper likes to visit,” for example.

Bragg got behind the cause. ”Initially, (Burg) wanted me to do 500 of them,” he said. They settled on printing 200.

”I said, ‘OK, we need to make him feel good, (and make Burg) feel good. But the other side of the coin is, if I’m going to go ahead and pay for it, what we want to do is (have) the profits, above and beyond what we paid for it,” go to the Alzheimer’s Association.

Since Bragg arrived at Aspen Ridge three years ago, the Alzheimer’s Association has been its annual cause.

”The first year I was here, we raised $10,000, the next year $15,000,” he said. This past year, through car washes, yard sales, a dinner concert by Tom Grant and other events, Aspen Ridge raised even more for the Alzheimer’s Association, and at 1:30 p.m. today, Aspen Ridge will hand the Alzheimer’s Association a $20,000 check.

The sale of Kelly’s book is the kickoff for the 2007 campaign.

Over the course of that late-November afternoon, the book sold some 60 copies. ”It looks like, at this point, we may very well at least do another 100 or 200 of them,” Bragg said.

‘A neat family’

This is not the first time a member of the Kelly family has been featured in The Bulletin. His older brother, Todd Kelly, paralyzed in an auto accident, was featured in a 1997 article for his high ranking in the Wheelchair Tennis Players Association and pioneering work riding a mono-ski. He is also a composer and played in the Carmen Marimba Band.

”Kind of a neat family, huh?” Aspen Ridge employee Lavoie said. ”I was kind of skeptical at first. This is an Alzheimer’s building, and he doesn’t have Alzheimer’s. Is it gonna work? Is he going to want to leave all the time? He’s younger than everyone. He gets along very well with the staff.”

But Bragg explained that Kelly is not in an entirely unique situation, being a younger person mixed among older folks.

”Not all the people over there have Alzheimer’s or dementia; some have other comparable medical issues. I guess what I see down the road is we might even have more intermingling with younger people. Unfortunately, with drug-related items and that sort of thing, I think we’re going to see more younger people in that type of setting. Because it’s still ‘what are the alternatives out there,’ you know, in terms of skilled nursing homes?”

Where the medical models go, it’s hard to say, he added. ”And of course, with all the money we’re raising for Alzheimer’s, we’re going to cure that, and we’ll be out of work, and we’re going to have to find something else to do, right?”