Bend home wins national green building award

Published 5:00 am Monday, March 26, 2007

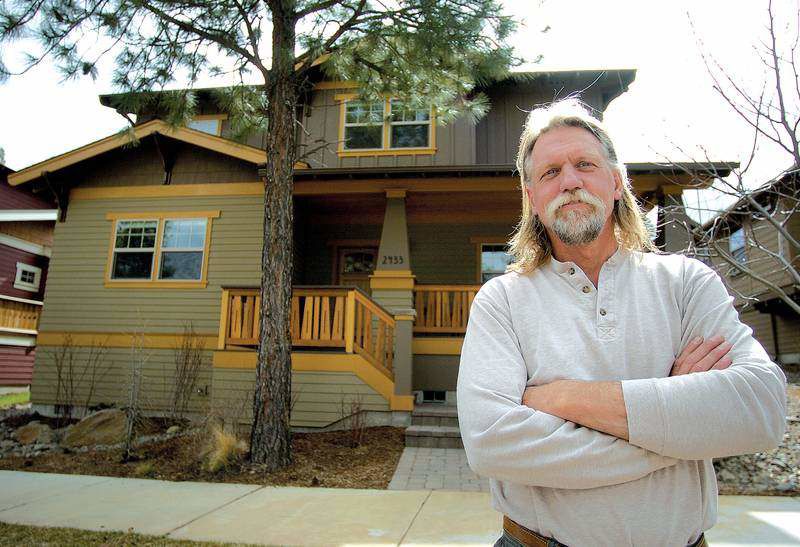

- Bill Hull stands in front of his award-winning Bend home.

The house that Bend builder Bill Hull built for his family last year on Labiche Lane looks pretty much like every other house in NorthWest Crossing.

The earth-tone paints. The craftsman-pillared porch. The steeply sloping lot.

It’s a little smaller than some, maybe, at 1,800 square feet. But other than that nothing – not even the cost – would indicate that it’s an innovative, cutting-edge example of modern ”green building” technology.

Which, as far as the National Association of Home Builders is concerned, is exactly the point.

The NAHB awarded Hull’s house the 2006 National Green Building Award for single-family custom homes Sunday at its annual green building convention in St. Louis, tapping it as the nation’s best example last year of an environmentally friendly home.

The reasons? It’s energy-efficient, in more ways than one, NAHB Environmental Communications Director Calli Schmidt said. It’s built with durable materials – wood floors, tile, concrete – that won’t need to be replaced anytime soon.

It’s light on water usage.

It doesn’t break the bank. And it doesn’t look or feel weird.

It’s the kind of house, in other words, that mainstream consumers would probably buy, whether they know about environmentally friendly building practices or not, simply because it’s a ”solid house,” Schmidt said. The NAHB’s builders believe that kind of marketability is what will fan the spread of greener construction throughout the American marketplace.

”When you have a house like that, the average consumer can see themselves living in it,” Schmidt said. ”They don’t feel like they’re living in a spaceship or something. Or with straw bales. Or, God forbid, that they are going to go to sell it someday and not be able to get their money back out of it.”

”Anymore,” she said, ”you don’t need to be crazy to be green.”

Building something green, but not crazy, was essentially what Hull said he set out to do.

A builder in Bend since 1985, Hull said he built a couple of oddball houses through the years, like an earth-berm home, for friends. For the most part, though, he built houses pretty much the way everybody else did for decades – throw up a wood frame, cover it with drywall and siding, cap it with a roof and call it good.

That began to change six years ago, Hull said, when he started building homes in NorthWest Crossing, where the subdivision requires every home to be built to rigorous Earth Advantage standards.

But his change really accelerated when he agreed to build a NorthWest Crossing house for Jim and Ruth Zdanowicz.

The Zdanowiczes wanted a house with a complicated mix of environmentally friendly aspects, from solar-power panels to a healthier ventilation system. Hull, feeling a little out of his element, took a class at Central Oregon Community College taught by longtime green-home designer Kathryn Gray to learn the skills he would need to build the Zdanowicz house.

It was a revelatory experience, Hull said. His key takeaway points: Today’s market is rich with building products that are designed to create healthier home environments while leaving a lighter footprint on the planet. And building an efficient, healthier home doesn’t have to involve great expense – just a change in the mindsets that builders and designers bring to their homes.

His house on Labiche Lane is built on a difficult lot. Its location on the north side of a hill made it tougher to incorporate solar features, Hull said, and its slope limited the size of some of the features he could install.

Still, the house is a machine, designed from the inside of its floors and walls to the configuration of its ventilation system to take maximum advantage of renewable energy, while leaving the least imprint on the Earth or on the people who live in it.

The key to its design is a hollow-cored concrete slab that underlays the back half of the house.

The slab, made of concrete poured around cinder blocks, draws from southern facing windows in the winter, but stays cooler than most of the house in the summer. The ventilation system pulls air out of its core in the winter and uses it to help heat the rest of the house. In summer, it does the opposite, pulling cooler air from the slab to help cool the house.

The top of the slab, stained a Tuscan-looking rust color with a ferrous sulfate fertilizer slurry, doubles as the kitchen, utility room and downstairs bathroom floor.

It’s all in the details

Beyond that, the home is packed with attention to detail – much of it hidden behind the walls.

It is framed with 2-by-4 studs that alternate on either edge of a 6-inch plate, according to Hull’s award application. Blown-in insulation seals all the gaps that are left, resulting in a frame where single studs no longer form uninsulated bridges between the inner and outer walls – a major source of heat loss in conventionally built homes.

The ventilation ducts are all sealed to avoid the loss of heat, and the ventilation system itself cleans the air, extracts heat from it, and turns it over with fresh air on a regular basis to keep lungs free from household fumes and contaminants.

There is no carpet – wood, cork and tile are the floor surfaces everywhere the concrete isn’t used.

The deck is recycled Trek. Much of the wood in the windows and framing is recycled, and the kitchen cabinets are made of wheat chaff particleboard covered with a wood veneer.

Hull and his crew recycled everything they could during the construction process. The landscaping is xeriscaped, the toilets are dual-flush and the faucets are all low-flow.

Gray, who helped design the house, used a computer model that predicted it would save about 48 percent of a typical power bill, Hull said. So far, his family’s electric bills have run between $115 and $150 a month this winter – low for an 1,800-square-foot house, but not as low as they are likely to go once the concrete slab warms to its full potential. He also spends about $40 a month on natural gas used for his fireplace and stove.

Most of the home’s innovations, with the possible exception of a solar water heater, added little or no cost above the normal cost of construction, Hull said. Altogether, he figures the house cost $140 to $150 per square foot to build – maybe $10,000 to $15,000 more than it would have cost to build a typical house.

Along that note, it’s wired for photovoltaic cells, but Hull took a pass on installing the cells themselves because they are too expensive relative to the power they produce.

”It’s a balance, right?” he said. ”I’d rather take the money and go on vacation, to tell you the truth.”

Green region

It’s the second year in a row that a Central Oregon house has taken the national association’s top green builder award.

Bruce Sullivan, the regional technical and sales consultant for Earth Advantage, lives in the house that won last year.

That’s partly a measure of how popular green construction has become in Central Oregon, Sullivan said. The Earth Advantage program certifies houses as environmentally healthy if the builders meet certain standards and agree to regular independent inspections. Last year, it certified 340 new Central Oregon homes, Sullivan said. The year before, it was 220. This year, he expects to certify 500.

Environmentally friendly building practices have taken off to a greater degree in the Pacific Northwest, and to a certain extent in the Southwest and in parts of the South, than they have in other parts of the country, Schmidt said.

The builders’ association came up with a set of criteria a few years ago to define ”green” standards and practices, hoping to help jump-start the thinking in other regions. That’s part of the goal with the awards, too, she said – to promote some new thinking, and to promote new thinking that is marketable at the same time.

There were about a dozen entries for the award program’s single-family home division this year, Schmidt said – a modest number, but up considerably from last year.

Around Central Oregon, the green-building mindset seems to be ”contagious,” Hull said. Builders have a plethora of green products to work with, ranging from nontoxic paints to wheat-board cabinets, and the thinking behind using them is ”contagious.”

He’d like to incorporate the kinds of green thinking he used on his Labiche Lane house into the rest of the one to two houses his W. H. Hull Co. builds every year. That is, if his customers want it.

”I’d like to,” Hull said. ” I mean I still have to eat, and that has always been the bottom line, right? But yes, I’d prefer to build with some of the new technologies and some of the new ideas. Yeah, definitely.”