Report: About 1 in 10 area jobs minimum wage

Published 5:00 am Sunday, April 8, 2007

- Report: About 1 in 10 area jobs minimum wage

Susanne Bahl, 46, has worked minimum-wage jobs in Bend since she moved here 10 years ago, primarily waiting tables full-time. For the past three years, she has been a full-time Central Oregon Community College student studying for an associate degree in social psychology, squeezing in her part-time job waitressing at The Grove.

”If it weren’t for the student loans, I wouldn’t be able to do it,” she said of her job that pays $7.80 per hour job, excluding tips. ”For seven years, I worked full time, but never got ahead – I barely made it month to month.”

Bahl lives with two cats in a $600-per-month rental house near downtown. With tips, she made about $12,000 last year. She has no benefits.

”I don’t go to the dentist, I don’t go to the doctor and I don’t have a brand new car,” she says, explaining how she makes ends meet. As a result, her rare health care appointments are more expensive to correct problems that might have been addressed earlier.

”It’s a catch-22,” she said, ”but my choices are pretty slim.”

From her perspective, Central Oregon job opportunities are limited for positions that pay more than minimum wage.

”When I see all these new houses, I think, ‘How do they afford these?’ ” she said. ”It seems like everyone in this town makes minimum wage – there’s no real industry here.”

Bahl is surprised that Central Oregon ranks low on the list of state regions with the most minimum-wage jobs.

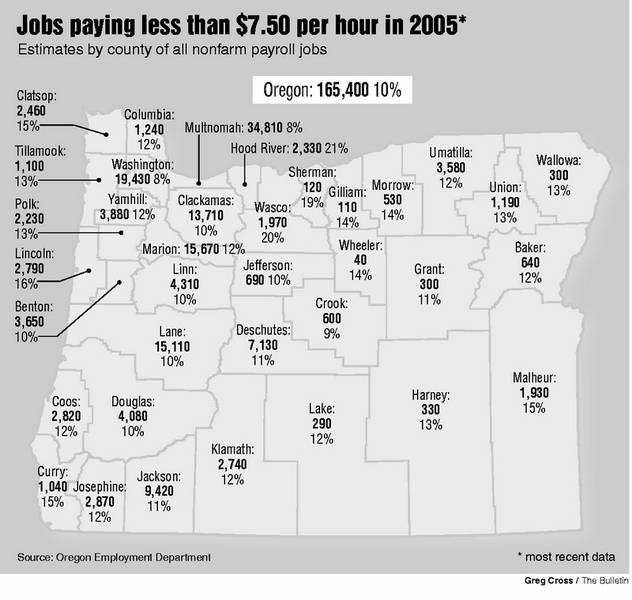

About 10 percent of Central Oregon jobs pay minimum wage, equal to the state average, according to a recent Oregon Employment Department report.

The data do not, however, mean Central Oregon jobs pay more than in other regions.

The data also run contrary to labor advocates’ belief that the region’s wages aren’t keeping up with the cost of living.

But the report indicates a healthy, average job market, economists say.

”Nothing sticks out, saying we are flooded with minimum-wage jobs,” said Steve Williams, regional economist for the Oregon Employment Department. ”We may have low-wage jobs, but this report is about minimum-wage jobs.”

In Deschutes County, 11 percent of all nonfarm payroll jobs in 2005 paid at or near minimum wage, which was $7.25 per hour then.

Deschutes County’s acute labor shortage has, for the past three years, made employers increasingly competitive in finding and retaining workers, helping push the county low on the minimum-wage list, Williams said.

”The local market is dictating higher wages to get people in the door,” he said. ”So we may have a lot of service-sector jobs, but not necessarily minimum-wage jobs.”

Additionally, Deschutes County has few agricultural workers, which reduces its share of low-wage jobs, said Art Ayre, the Oregon Employment Department economist who wrote the report.

But the county has a higher-than-average share of workers in recreation and accommodations (tourism-related jobs like those in hotels), and a slightly higher-than-average share of workers in restaurants, he said.

”However, wages in these last three industries are a bit higher in Deschutes County than they are statewide,” Ayre said, ”which slightly reduces our estimates of minimum-wage workers in those industries.”

In 2005, the most recent data available, Deschutes County jobs in all industries, private and public, paid an average of $31,492 per year, Williams said.

In the minimum-wage report, Jefferson and Crook counties had some of the lowest percentages of minimum-wage jobs in the state, with 10 percent each.

Typically, the highest number of minimum-wage jobs in Oregon are along the state’s borders, and the more metropolitan counties tended to have fewer minimum-wage jobs, the report found.

That’s why Jefferson and Crook counties are so unusual – they are rural, which typically means they would have more low-paying jobs, Ayre said.

But these counties have higher-than-average concentrations of jobs in the wood products and wholesale trade industries, where wages are higher. Wholesale trade is the business of distributing merchandise to retailers, or being the ”middle man” between producers and retailers.

Bruce Daucsavage, president of Prineville’s Ochoco Lumber Co., has said Ochoco workers make $40,000 to $50,000 per year, plus benefits.

Bright Wood Corp., which employs 1,050 people, pays $11 to $26 per hour, President Dallas Stovall has said.

In Jefferson County, the average pay was $28,401 in 2005, Williams said.

In Crook County, it was $31,664, where manufacturing jobs pushed the average pay higher.

Recent manufacturing layoffs, however, may lead to more minimum-wage jobs in Crook and Jefferson counties, Williams said.

”If those jobs are permanently gone and not replaced by the company or some new business that comes to the area, that has the potential to change the industry makeup,” he said, adding that it remains to be seen how recent layoffs at Bright Wood Corp. in Madras, Columbia Aircraft Manufacturing Corp. in Bend and SeaSwirl boats in Culver will affect the economy.

As the region continues to evolve from its rural roots to a more urban environment, Williams said the job market becomes more diverse, which could mean that jobs lost in one sector get absorbed by another.

”It means new jobs in a whole gamut of industries,” Williams said. ”(Diversification) is good for an area, but it also can have potential drawbacks.”

Drawbacks could include more low-paying jobs, which could lower average wages in Central Oregon, he said.

”The biggest thing to watch in Central Oregon is, are we going to keep adding people?” Williams said. ”Growth is our biggest factor in the overall health of our area.”

One-quarter of the state’s minimum-wage jobs are in the food-services and drinking-places industry, the report found.

Other areas with many minimum-wage jobs include administrative and support services, agricultural crop production, food and beverage stores, accommodations such as hotels and motels, general merchandise stores and gasoline stations.

The Employment Department report looked at where minimum-wage jobs are distributed throughout the state. Since no reliable data exist detailing wages of every job by county, the department estimates minimum-wage jobs in each region, based on the state data.

Raising the floor

Oregon’s minimum wage is the second highest in the country behind Washington’s $7.93 per hour, but below what the Northwest Federation of Community Organizations considers a ”living wage” of about $11.30 per hour for a single person in Deschutes County.

But a minimum-wage earner is typically a second, third or fourth wage earner in a household, Williams said. Additionally, Oregon minimum-wage workers tend to be young and to work part time in the retail or restaurant industry.

But Bend resident Bahl, who doesn’t fit the profile of a typical minimum-wage worker, knows too well the extreme difficulty of surviving off the minimum wage alone.

”Most people assume minimum-wage workers are kids,” Bahl said, adding that some people criticize her for working as a waitress at 46.

She loves her job but says Bend’s job options are limited. She hopes to move to Portland soon to attend Portland State University full time.

”I’m excited to go to Portland and have more opportunities for restaurants (to work in),” she said.

She hopes to land steady work year-round. In Bend, work and tips slow with the seasons.

The minimum wage doesn’t get people far these days, says Michael Funke, organizer for Jobs with Justice, a labor community coalition that advocates for economic justice, workers’ rights and the right to organize.

”I’m glad to hear, if this is true, that more workers are getting paid more than minimum,” Funke said. ”But how much more becomes the issue, and the fact is, whether you’re getting $7.80 per hour or $9 per hour, it’s still a very low wage for our community.”

Funke pointed to the median price of a Bend house – $352,000 in 2006 – and high transportation fueled by rising gas prices.

Many employers complain that a rising minimum wage hurts their bottom line and leads to price inflation for consumers, but Funke disagrees.

”The whole floor moves every time the minimum wage goes up,” he said.