A new rite of passage for fish hatchery

Published 5:00 am Wednesday, June 27, 2007

- A new rite of passage for fish hatchery

MARION FORKS — The salmon fry were sucked up a plastic tube, one by one. They traveled from a holding tank up a few feet to a device overhead, which sorted them by size before sending them shooting down one of six tubes, winding down like a mini water slide.

The tiny fish, most just a few inches long, plopped out of the tubes into another shallow tank. From there, they funneled into a contraption that clamped them in place and, with a single swipe of a blade, removed a flap of fatty tissue from their backs.

Now permanently marked as hatchery fish, the fry dropped back into yet another tube and were returned to their holding pond. There, they’ll eat and grow for almost a year before being released into Oregon’s rivers to make their way to the ocean.

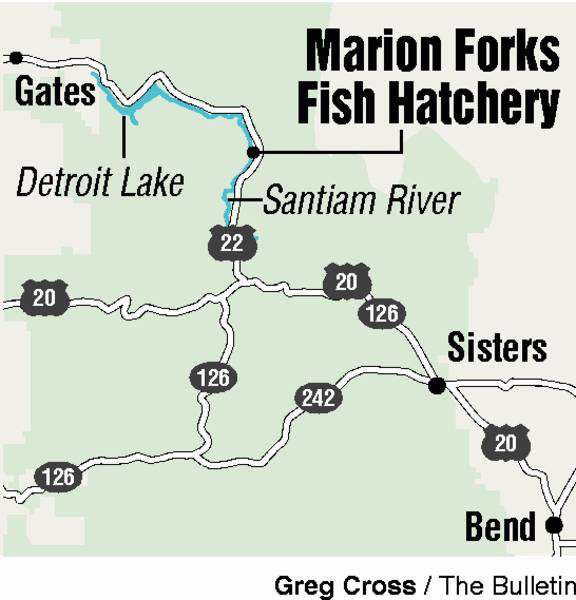

This automated fish-marking system, housed in a mobile 44-foot trailer that can travel from hatchery to hatchery, was put to use at Marion Forks Hatchery west of Santiam Pass on Tuesday. It is the latest technology that the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife is using to make the previously labor-intensive process more efficient.

“We need to mark a lot of fish statewide during a short time in the spring, early summer,” said Christine Mallette, assistant propagation program manager with the state agency.

And the $1 million, equipment-filled trailer, called the AutoFish System, is a way to mark millions of hatchery fish in a short time period, she said.

“In the past, we’ve done most of it using crews of people who had to handle every fish,” she said, adding that handling the fish requires anesthesia, can cause fish to lose some of their scales, and stresses the fish out.

But marking them by removing their adipose fin — a bit of fatty tissue that doesn’t serve any physiological function, located between the dorsal fin and the tail — distinguishes hatchery-raised fish from wild runs of salmon. That way, Mallette explained, Oregon can have fishing seasons in which anglers are allowed to keep the fin-clipped fish, but throw back wild fish that have their fins intact, helping to protect the wild salmon runs.

Tracking the fish

The automated system can also tag fish by shooting a tiny stretch of wire that has a code on it into a fish’s snout.

The identification tag is recovered later when the fish are caught or return to the hatchery after migrating to the ocean and back. It is used to gather information about things like how well fish survive when they get to the ocean, their age when they return, and whether rearing conditions have an impact on survival rates.

“With its help, we can track the fish’s life,” Mallette said.

This is the first year that the automatic fish-tagging trailer has been used at Marion Forks Hatchery, said Greg Grenbemer, manager of the hatchery. Before, the hatchery would have to hire a seasonal crew of about 20 people, usually high school students, to mark and tag about 1.7 million chinook salmon raised at the hatchery.

“Their quality was good,” he said. “The trailer’s excellent.”

Having the process automated, where it only takes one technician and a handful of people who manually clip the fins, saves a lot of work and headaches that come from managing a large, temporary and sometimes unreliable work crew, he said.

In places like Marion Forks, more than 60 miles from both Bend and Salem, it can be hard to find temporary workers, said Geoff Gribble, fish stock identification biologist and technician for the fish-tagging trailer.

But with the trailer staffed by him and about four others manually clipping the fins of fish that were too small or too big for the machines, they can mark more than 60,000 fish a day, sometimes even up to 85,000 in an eight-hour period.

When operating, the trailer is filled with the hum of the machines and the clicking sounds of air cylinders that open and close gates and channels, and the floor is covered in water.

Tiny adipose fins, about the size of half an eraser head and separated from their former owners, stick to the outside of the cutting contraptions.

Before and after

Fish are passed through a series of gates until they get to clamps that hold them in place as a small steel blade slices off the fin. A camera takes before and after pictures of the fish’s back, comparing them almost instantaneously to ensure that the cut is good and complete.

“If so many pixels are gone, then they will count it as a good clip,” Gribble said. Having a good clip is important, he said, because otherwise the fin might regenerate and a fisherman could mistake it for a wild salmon.

If a batch of fish is going to be tagged with a coded wire, at this point a hollow needle injects the snippet of wire into the fish’s snout. Only a small percentage of fish are tagged, however.

Once the clipping and tagging is complete, a trap door opens, dropping the fish back into another tube, which leads back outside the trailer to a holding pond. The fish doesn’t have to be anesthetized, and in fact the set-up depends on their being awake and swimming through the different stages, Gribble said.

The state has a fleet of four trailers that visit the bigger hatcheries around Oregon, including the Umatilla hatchery east of the Cascades, Mallette said.

“We go everywhere from La Grande to Astoria, throughout the valley,” Gribble said. “Wherever there’s a hatchery, we go.”