Cursive writing – taught with a flourish

Published 5:00 am Thursday, August 23, 2007

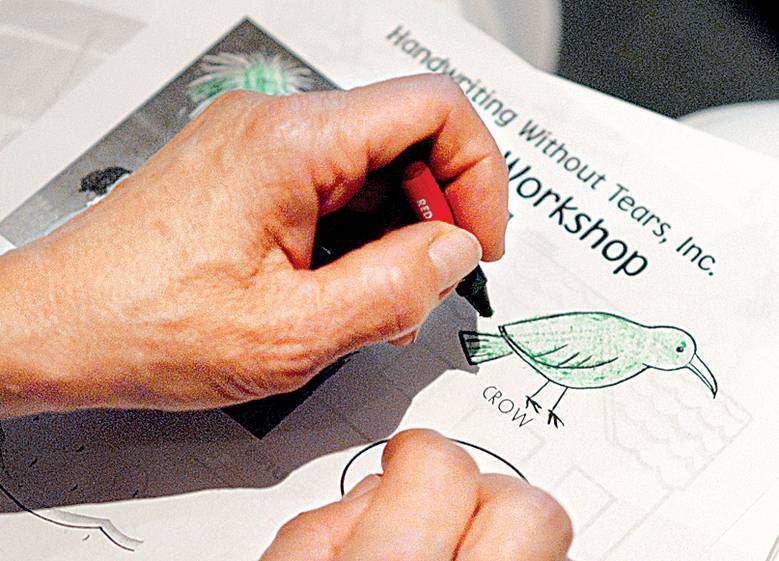

- Phyllis Burge, an instructional assistant at Ochoco Elementary in Prineville, practices coloring with her nondominant hand in order to simulate what it is like to learn how to write.

Students taking the SAT this school year, pay attention: While memorizing flashcards filled with vocabulary words and brushing up on geometry, it would be wise to also practice cursive writing.

In an age when kids often start using computers before they learn to write, College Board numbers show that on average, students who wrote in cursive on the SAT scored slightly higher on the essays than those who printed, and some studies show that teachers and adults often pick out kids with neat handwriting as the smartest. If writing legibly is a task that leaves the floor littered with crumpled paper, then help may be on the way to some Central Oregon classrooms.

That’s where Cathy Van Haute and Handwriting Without Tears comes in.

The 1 1/2-day seminar, which uses a penmanship curriculum designed to bring fun and play back into the sometimes frustrating and painful subject, started Wednesday in Hitchcock Auditorium at Central Oregon Community College and is sponsored by the High Desert Education Service District.

Today is the second day of the seminar, and it will focus on cursive penmanship for kids between third and fifth grades.

On Wednesday morning, about 70 educators filled the auditorium to hear Van Haute, an occupational therapist who works at a preschool in Omaha, Neb., and as a presenter for the Handwriting Without Tears program, who was in Bend to provide teachers with a new way to teach handwriting.

Dawn Williams, a kindergarten teacher at Bear Creek Elementary in Bend, was at the seminar looking for ways to give her students a positive start in handwriting.

Williams, who has taught kids in third through sixth grades, said she’s seen students struggle with writing for years.

“For kids who struggle, their frustration level is high, even if handwriting is not directly related to what they’re doing,” she said. “This is a good way to start with kindergarteners in a positive, nonthreatening way.”

Plenty of challenges

According to Van Haute, North America is one of the few places where children are expected to learn two different styles of writing, both printing and cursive.

Add to that, children today aren’t developing motor skills because of the changing way kids play, increasingly with electronic games.

“Their motor skills stink because they don’t go outside and play,” she told the crowd of teachers.

Van Haute first took an interest in handwriting after years of working as an occupational therapist.

“The number one referral I would get was for handwriting,” she said. She took a continuing education course that introduced her to Handwriting Without Tears. Now she travels the country presenting information about it.

Van Haute has even tutored physicians to try to make their penmanship more readable.

“You’re never too old,” she said. “It’s a vital skill.”

She has visited schools where, she said, principals and teachers were reluctant to implement a handwriting curriculum now that the age of computers has arrived.

“When we’re still sending kids to bed hungry; don’t tell me that every kid has a laptop,” she told one administrator. “We still show what we know through writing.”

There are other handwriting programs that schools in the area use as well, like Zaner-Bloser, which focuses on four basic concepts to push legibility, and Denelian, which points to an ideal slanted script. But Handwriting Without Tears is gaining in popularity. The program was started by Jan Olsen, an occupational therapist who has specialized for almost 30 years in handwriting, and now more than 2 million kids around North America and Europe use the program.

“There are a lot of things they do before they pick up a pencil,” said Natalie Godat, a kindergarten teacher at Ochoco Elementary School in Prineville. “The letters are made with the minimal amount of difficulty.”

Godat’s school will implement the curriculum as a pilot program this year in kindergarten and first grade classrooms, and Godat hopes the program will help cut down on the frustration she’s seen in her students through the years.

“They have a lot of self-esteem issues,” Godat said. “I think it affects their reading. They’re not able to process what they’re reading and writing — the connections aren’t there.”

Going for fun

Handwriting Without Tears is designed to make handwriting instruction fun, and Van Haute worries that the fun stops too early in today’s education system.

“Let them play, with Play-Doh and sidewalk chalk and Legos,” she said. “It doesn’t all have to be paper and pen. Kids learn through play.”

The curriculum, which starts at the pre-kindergarten level and goes through fifth grade, includes songs, puppets and other props for younger kids.

It begins with an emphasis on spatial instruction — knowing top from bottom and left from right — and developing motor skills. Many of the early activities for preschool- and kindergarten-age kids don’t involve writing at all, but instead focus on using props like pieces of wood to form letters. It also focuses on making sure kids hold writing implements correctly.

Cursive is introduced in third grade and instruction continues through fifth grade, and the curriculum requires no more than 15 minutes per day.

“It never ceases to amaze me how many ways kids find to hold a pencil,” said Juli Malone, a kindergarten aide at Ochoco.

And she’s seen plenty of kids get frustrated with their inability to write well.

“The ones that are perfectionists, they get frustrated and angry,” Malone said. “Sometimes they wad up their paper and throw it on the floor, or refuse to do the work.”

While the popularity of computers has certainly decreased the time kids spend practicing penmanship in the classroom, Van Haute also thinks society’s concern with competition has led it to equate writing in preschool with intelligence.

And without a proper foundation in handwriting, she said, kids will always have to place a focus on it, which can take away from course work.

“It takes effort if it’s not an automatic skill,” she said. “Part of their brain will go to the physical act of handwriting.”

If Ochoco Elementary and other schools are successful, the neglect of handwriting will end in Central Oregon.

“It’s such a lost art anymore, and it’s important for kids to know,” Godat said.