Ranching heritage

Published 5:00 am Sunday, September 2, 2007

- Ranching heritage

If there’s a folk hero in the Steens Country, his name is John W. “Pete” French. Although he spent only 25 years in this region, from 1872 until his death in 1897, his name is branded everywhere, from the community of Frenchglen to ranches and historic sites across more than 40 miles of the Blitzen Valley.

French was just 23 years old when his employer, a wealthy California stock grower named Hugh Glenn, entrusted him with driving a herd of 1,200 cattle northward into then-undeveloped Eastern Oregon. Within 20 years, French increased the quality and size of the ranch herd to 45,000 through careful management and breeding. An entrepreneurial rancher, he expanded his land holdings to more than 190,000 acres, from Steens Mountain to Malheur Lake. His business acumen, however, was not appreciated by individual homesteaders, one of whom eventually shot and killed him.

French had his headquarters at the P Ranch, near Frenchglen, with additional overseers at the Sod House Ranch and the Round Barn. The long barn at the P Ranch can still be visited today, as can several buildings at the Sod House Ranch near Narrows. Most intriguing, perhaps, is the Pete French Round Barn north of Diamond. Now a state heritage site, this circular barn was used for sheltering horses and breaking wild mustangs during the long winters.

The Round Barn is located on the Jenkins Ranch, in its fourth generation of family ownership. Richard (Dick) Jenkins, Jr., has turned over the day-to-day operation to his son, Richard (Rich) Jenkins III; Dick, at age 66, has semi-retired to his other passion: sharing with visitors the heritage of ranching in the Steens Country. Hard by the historic site, his Round Barn Visitor Center incorporates a bookstore and gift shop with the Jenkins Family Museum, with household wares and collectibles that once belonged to his parents.

To get there, turn east off state Highway 205 on South Diamond Lane and follow the signs 17 miles through the Diamond Craters Outstanding Natural Area, a unique volcanic region whose lava flows were created an estimated 25,000 years ago.

Jenkins Heritage Tours, operated from the visitor center, highlight the ranching history of this region, taking in old buildings, equipment and artifacts. “Ninety percent of Harney County ranches are family-owned,” Dick Jenkins told me. “Our family has been here since 1880, and we’ve made no significant land changes since 1916.” Full-day tours run $110 per person, including lunch.

— John Gottberg Anderson

By John Gottberg Anderson • For The Bulletin

FRENCHGLEN —

The Steens Country is desert, yes. But it’s probably unlike any other desert you know.

It has rivers and swamps. It has hiking, fishing, hunting, cross-country skiing and land sailing. It has millions of birds: raptors, waterfowl and migratory birds. It has pioneer hotels, pioneer homesteads and fourth-generation cattle ranches. And, at its heart, is a massive mountain that has long inspired a political tug of war between those who would maintain it as open range and others who would preserve it as wilderness.

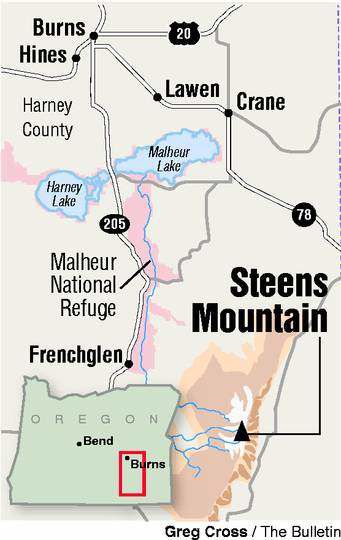

A four-hour drive southeast of Bend, Steens Mountain is 30 miles long and tops out nearly two miles above sea level. Taller than Mount Bachelor and almost as high as the Three Sisters; it retains pockets of winter snow into August. A 28-mile drive up its gently rising west slope will take you through eight different vegetation zones, including riparian wetland; woodlands of juniper, pine and aspen; sage land and subalpine tundra.

Then you’re at the summit. The terrain that appeared so moderate on your ascent now assumes a different face. Dramatic canyons like Kiger, Little Blitzen and Big Indian leave you to wonder why you didn’t notice them until you reached the top. And when you look off the East Rim, straight down (or so it seems) one full mile to the ivory-white Alvord Desert below, you get a sense of the geological forces that once pushed this fault-block mountain so imposingly above the surrounding land.

A hotel with no keys

My home-away-from home in the Steens Country is the Frenchglen Hotel, 60 miles south of Burns on state Highway 205. The eight-room inn, built in 1916, hasn’t been significantly renovated since the late 1930s when a couple of bathrooms were installed for guests to share. Before that, I guess, there were outhouses.

A designated Oregon State Heritage Site, the hotel has been owned for nearly 17 years by John Ross, a Bend native who came off a fish-processing ship in remote Alaska having decided he liked the quiet life. Now 46, Ross and his wife, Glenda, don’t stray far from the inn between March and November, but they take the winter off to travel a bit and get a taste of city life. The population of Frenchglen, after all, is only 11.

The rooms are tiny and basic. There are no phones, no TVs, no internet access. No one locks their doors; in fact, guests are not even offered keys. The narrow staircase to the second floor makes you wonder what you’d do in the event of a fire. I suppose the goats that continually bleat from their backyard pen would sound an alarm.

But the family-style dinners are wonderful (you must reserve ahead, as the hotel can accommodate no more than 24 diners) and there’s great camaraderie among guests. I shared one night’s meal with Bend attorney Karla Nash, who was touring the region with her two young children, and the Hunter family of four, down from Portland for bird watching. We enjoyed baked chicken, a spinach-artichoke casserole and a rice dish, followed by a delicious marionberry cobbler with ice cream. The next evening, seated with guests from Portland, Eugene and Sacramento, I reveled in a beef roast, broccoli and au gratin potatoes, with apple crisp to finish.

My most memorable meal in Frenchglen was a lunch with 80-year-old rancher Everett Hilbert, who stopped by for a bowl of soup after completing his morning chores. Hilbert, who had been working the Steens since he moved down from Pendleton back in the 1950s, regaled me for the better part of an hour with tales of chasing wild horses and rounding up free-range cattle from Foster Flat to Hart Mountain to the Double O spread.

He assured me that some of the Steens’ famed Kiger mustangs had come from out Beatys Butte way. He knew his wild horses, he said, because he’d been thrown from the steeds more than once while breaking them. Suffered a broken back once, a broken neck another time, but he was still riding.

Climbing the Steens

I saw no shortage of open-range shorthorns in my morning drive up 9,670-foot Steens Mountain, which is named for 1860 Army surveyor Major Enoch Steen. Steens Loop Road climbs to within a short hike of the summit. Contained within the Steens Mountain Cooperative Management and Protection Area, which is administered by the Bureau of Land Management, the road offers a painless route to the top despite being all gravel.

The North Steens Loop Road begins opposite the Frenchglen Hotel. The first three miles are like driving on an old washboard, across a section of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge to the bare-bones Steens Mountain Resort, the Donner und Blitzen River bridge and the turnoff to the Page Springs campground. Don’t let the rough road scare you away; driving conditions improve to well-graded as soon as you pass the snow gate. It’s no problem to maintain the speed limit of 35 miles per hour most of the way to the summit.

The climb is relatively mundane for the first 17 miles, until you reach Fish Lake, where there’s a campground in a quiet woods and a short dock from which youngsters cast lines for trout. The elevation here is about 7,500 feet; even at 8 on a morning in late August, a heavy frost cloaked the ground. A smaller campground in an aspen grove known as Jackman Park is a couple of miles farther.

Keep driving uphill until, about five miles from the end of the road, you see a sign pointing left to the “Kiger Gorge Overlook, 1/4 Mile.” Don’t miss this spectacular panorama. The Steens’ canyons were gouged by glaciers in the last Ice Age, more than 10,000 years ago. Kiger is the only north-running canyon off the mountain; its eastern slope was still shadowed from the sun during my morning visit, but the lush green line of trees surrounding its central creek was already in sharp focus, as were the multicolored scrambles of vegetation accenting the gray scree on its western wall.

As you continue on your drive, you’ll want to pull off to the side to look down westward-flowing Little Blitzen and Big Indian gorges. I’m told they’re most picturesque in June, when alpine wildflowers cover the slopes. Further along is Wildhorse Canyon and its seminal Wildhorse Lake; the view of this chasm requires a 1/4-mile hike into the roadless, federally mandated Steens Mountain Wilderness after you reach the summit parking area.

You’ll want to tarry awhile atop Steens Mountain, probably at the spectacular East Rim Overlook, soaking in the views of the Alvord Desert, Mann Lake and the Mickey Basin. But when you turn around and head back downhill, think twice before you take the alternative South Steens Loop Road to Frenchglen.

It’s tempting to make this trip a loop drive, but unless you’re behind the wheel of a four-wheel drive or other high-clearance vehicle, a rugged, heavily rutted four-mile section of road along Big Indian Gorge may make you question your decision to drive this way. Most drivers are happy to have returned on the same North Loop Road that they took uphill. (Steens veterans say they prefer to drive up the South Loop Road rather than down it, because it gives them an inside look at the gorges not seen from the North Loop Road. The junction is 10 miles south of Frenchglen off state Highway 205.)

Oregon’s driest desert

That stunning white expanse you saw from the East Rim Overlook? It’s the Alvord Desert, a chalky sheet of alkali so hard you can drive your car upon it. Sitting in the rain shadow of Steens Mountain, the desert averages only five inches of precipitation per year and is the driest place in all of Oregon.

Make the 90-minute drive from Frenchglen and you’ll be confronted by a stunning scene: Eleven miles long and six miles wide, the Alvord Desert it is pure white and entirely devoid of any apparent moisture, vegetation or life form.

Yet, chances are, you’ll find tents pitched on the surface of this ancient playa. You’ll see all-terrain vehicles and dirt bikes as well as “land sailors,” hand-manufactured vehicles best described as small wheeled sailboats. When the wind is up, they streak across the alkaline surface at remarkable speeds. And when their day of play is complete, these speed lovers can clean up in primitive Alvord Hot Springs, covered by a simple lean-to.

To reach the Alvord Desert from Frenchglen, you must drive an hour south on state Highway 205, past the prosperous Roaring Springs Ranch and the broad Catlow Valley, to the tiny community of Fields, just north of the Nevada border. Here you’ll turn north 18 miles on the Fields-Denio Road. If you don’t mind a 90-mile drive on a gravel road, you’ll eventually reach state Highway 78; a left turn there will bring you back in the direction of Burns.

Malheur wildlife

Frenchglen sits at the southern end of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, considered one of the crown jewels of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service-managed system. Set to observe its 100th birthday in 2008, the refuge was established by President Theodore Roosevelt; it claims more than 320 bird species and 58 mammal species in its 187,000 acres of habitat, including 120,000 acres of wetlands.

Each September, sandhill cranes gather in the refuge’s swampy southern valley, along the Donner und Blitzen River, before migrating to their wintering grounds in California. This magnificent bird, gray with a red forehead, has been around for more than 9 million years, according to fossil records. About 200 pair breeds in the Malheur refuge; I was fortunate to spot a couple in the Knox Ponds area.

As long as you don’t object to driving on gravel roads — if you’re going to spend much time in the Steens Country, you’d better get used to it — you can visit a number of outstanding wildlife-viewing sites. In my short visit, I identified a couple dozen species of birds, as well as mule deer, a coyote, a jackrabbit and various smaller rodents. Orient yourself at the refuge headquarters office and museum on Sodhouse Lane, six miles east of state Highway 205 (turn off at the Narrows store and gas station), and go from there.

John Gottberg Anderson can be reached at janderson@bendbulletin.com.