Doctors fear warnings behind suicide increase

Published 5:00 am Thursday, September 13, 2007

- Doctors fear warnings behind suicide increase

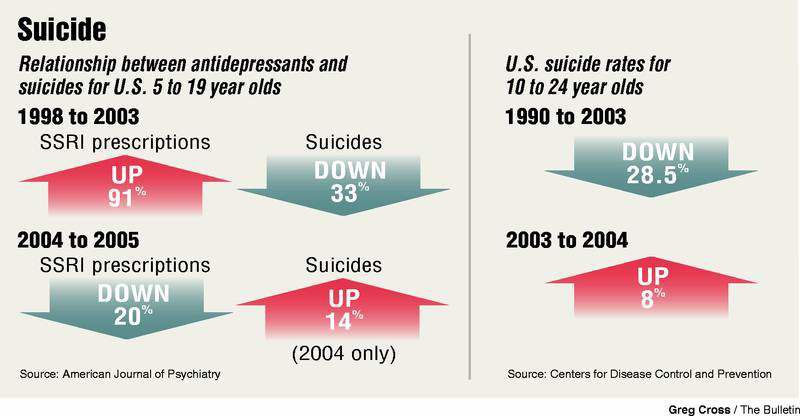

In recent years, the Food and Drug Administration has followed the advice of expert advisory panels to warn doctors about the potential link between certain antidepressant medications and suicide, particularly for children and young adults. But new data showing an increase in suicides coinciding with the drop in antidepressant prescriptions have many of those same experts thinking they might have been wrong.

In October 2003, the FDA issued a public health advisory regarding several reports of children and teenagers taking antidepressants who attempted or committed suicide. A year later, the agency ordered manufacturers of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, known as SSRIs, to include a black box warning on labeling about the possibility of an increased risk of suicidal thoughts in pediatric patients taking the medications.

The SSRI class of drugs includes Prozac, Zoloft, Paxil and Celexa.

Researchers led by Dr. Robert Gibbons, director of the Center for Health Statistics at the University of Illinois at Chicago, found the warnings led to a sharp drop in SSRI prescriptions for children. Before 2003, the number of SSRI scripts written by doctors had risen steadily each year since 1987. From 2003 to 2004, however, prescription rates for children younger than 14 dropped 20 percent, and rates of new prescriptions dropped 30 percent.

Meanwhile, youth suicide rates increased 14 percent from 2003 to 2004, the largest single-year increase since federal authorities started tracking suicide rates in 1979. The uptick broke the steady decline in suicide rates that had been occurring since 1998.

The researchers found a similar effect of SSRI warnings in the Netherlands, where a 22 percent decline in child and adolescent prescriptions for SSRIs coincided with a 49 percent increase in suicides from 2003 to 2005.

“People need to know if the antidepressant medication they are taking is increasing or decreasing their risk for suicide,” says Dr. Hendricks Brown, a professor in the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the University of South Florida and a co-author of the study. “It would be bad if antidepressants were causing an increase in suicides, in which case the appropriate policy would be to restrict their use in adolescents. It would be even worse if FDA policies led to less treatment of depression and more suicides.”

In contrast, prescription rates for adults older than 60 continued to increase, and suicide rates for older adults continued their uninterrupted decline.

Similar findings

The results mirrored findings issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention last week showing an 8 percent increase in suicide rates for 10- to 24-year-olds. The CDC study used data from the same source — the National Vital Statistics System — but looked at a slightly different age group.

“In surveillance speak, this is a huge and dramatic increase,” says Dr. Ileana Arias, director of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

But Arias cautioned against drawing conclusions from correlation between antidepressant use and suicide rates.

“As much as we would like to attribute suicide to any single source, so that we can fix it quickly, unfortunately, we can’t do that,” she says. “So while things such as antidepressant medication may have a role in either ideation or actual fatal suicide, probably it’s not the only factor.”

While the study did not examine the causes behind the increase, Arias said other factors that increase the risk for suicide include previous suicide attempts, a family history of suicide, depression and mental illness, family dysfunction, social isolation, alcohol and drug use, stressful life events, having access to a mean for suicide, exposure to the suicidal behaviors of others and incarceration. Experts will closely watch what the final suicide rates for 2005 show. That data will not be available until December.

Black box warning

Dr. Tom Laughren, director of the FDA’s Division of Psychiatric Products, said the increased suicide rate was discussed at an advisory committee meeting late last year, but the agency still opted to extend the black box warning to young adults.

“It’s true that prescribing in pediatric patients has come down and that coincides with this one-year uptick in adolescent suicide. So obviously, that’s a concern,” he says. “On the other hand, we do as a regulatory agency have an obligation to alert prescribers and patients of risks that we find with drugs that are being used. And so it’s a dilemma for us, but clearly, it’s a concern.”

Laughren says the advisory committee last year also urged the agency to modify the black box warning with the statement that depression itself is a major predictor of suicide. But it’s not clear whether that will be enough to urge primary care physicians to continue to prescribe the medications.

Gibbons, who was a member of the 2004 FDA advisory panel that first voted 15-8 in favor of placing a black box warning on SSRI prescriptions, says many experts fear that “doctors, particularly general practitioners, would be terrified of prescribing SSRI drugs for children” because of the suggested link with suicide.

Gibbons and Brown wrote in their study that the FDA issued its warnings based on data with major limitations. For one, the studies looking at SSRI use in children did not find any suicides, and the adult studies reported only eight suicides, only five of which were by patients on SSRIs. With too few suicides to give an accurate picture of the risk, the studies relied on suicidal thoughts as a proxy. Other studies that have reviewed medical records of children who committed suicide found that very few were on SSRIs at the time of their suicide. The FDA studies also excluded those patients who were actively suicidal, thus the agency lacked data on those who are at highest risk for suicide, the researchers said.

Previous research by Gibbons compared suicide rates for children ages 5-14 in each county of the United States from 1996 to 1998 with county specific data on SSRI prescriptions.

The study, published last year in the American Journal of Psychiatry, found that in counties with low prescription rates, the suicide rate was as high as 1.7 per 100,000. In counties with high prescription rates, suicide rates were as low as 0.7 per 100,000.

“We found that the counties with the highest prescription rates for SSRI drugs had the lowest suicide rates in children and adolescents,” Gibbons says. “This is just the opposite of what you would predict if SSRIs were producing suicide.”