ADA compliance: Cost is in the details

Published 5:00 am Saturday, October 6, 2007

- ADA compliance: Cost is in the details

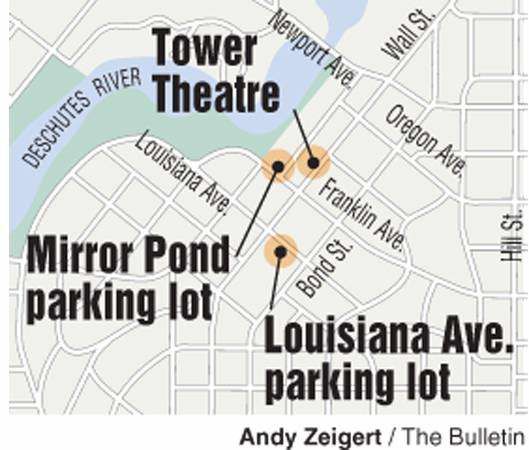

When contractors’ estimates to fix a handful of accessible parking spaces in the Mirror Pond parking lot in downtown Bend came in twice as high as expected, Bend officials ordered city crews to do the work.

Earlier this week, workers pulled out part of an old walkway and poured a new concrete curb and walkway around one space.

They are small steps for a city that has faced questioning by accessibility advocates for letting its Americans With Disabilities Act projects run thousands of dollars beyond cost estimates.

Recently, the Bend City Council pressed city officials harder than in the past on why the dozens of accessibility projects the city must complete are behind schedule and over cost.

Their answers show that a combination of factors, including rising construction costs, a lack of qualified contractors, high construction standards and little competition, is at work.

The cost issue does not appear to be letting up, as work to improve bus stops is now averaging about $20,000 per stop. Officials earlier this summer said they expected to be able to fix many bus stops for about $1,500 each.

The added money often goes toward improving adjacent sidewalks and curb ramps, not just the concrete waiting pad, officials told the council earlier this week.

The city faces repair timelines it agreed to in settlements to two separate lawsuits. In a 2004 settlement with the U.S. Department of Justice, the city agreed to a 10-year timetable to fix parking spaces, curb ramps, sidewalks and buildings.

While some of those projects have moved forward, many have lagged far behind schedule.

As of last week, the city had spent about $172,000 on 43 specific improvement projects, many of which have not yet been completed, according to city documents.

In December, the nonprofit Oregon Advocacy Center sued the city over its bus stops. The city agreed in a May settlement to make all of its bus stops accessible within five years.

More than asphalt and cement

The underlying problem when it comes to such projects is more complicated than simply the rising cost of asphalt and fuel.

The Americans with Disabilities Act spells out in exacting detail the standards to which projects must be completed. For example, the side-to-side slope of a sidewalk can’t exceed 2 percent.

If a sidewalk is 6 feet wide, that means one edge can be no more than about 1½ inches higher or lower than the other edge.

Similar rules apply to asphalt parking spaces, curbs, the angles of curb ramps and the size of gaps between sidewalk sections.

“The tolerances are so tight that the contractors are putting a little bit of money in there because of mistakes,” said Bob O’Neal, a project manager for the city. “If they make mistakes, they have to tear it out and do it again.”

It’s not just the precision with which contractors must smooth out cement and pave asphalt that drives up the cost.

City officials said last week that there are only a handful of contractors in Central Oregon that they feel are qualified and skilled enough to do the work and meet those requirements.

That means there is little competition.

Earlier this year, the city requested bids from three different companies to make a pair of parking spaces in front of the Tower Theatre accessible to people with disabilities. One company did not want to even touch it, O’Neal said. The May invoice from low bidder Wilson Curb came in at $45,420. Adding in design work beforehand, including verification from outside consultants that the two spaces would meet ADA requirements, the project ended up just shy of $60,000.

“We got all that information from those guys, and we questioned it, too,” O’Neal said. “It was high.”

Facing stiff questioning on the city’s ADA progress from the City Council on Wednesday, City Manager Andy Anderson attempted to justify the high costs.

“We’ve been criticized pretty roundly for this stuff costing too much, but those all come with guarantees,” Anderson said.

Still, outside observers said the amounts the city is having to pay seem high.

“It seems pretty darn high to me,” said Wayne Yarnall, a nonprofit ADA consultant in Portland. “It’s just unclear what really cost the money. Probably it’s the curb interface, but even that sounds high.”

A Eugene official said his city took care of its ADA compliance issues years ago. Now, most construction that has to meet ADA requirements is part of a larger development, such as a parking lot for a new building. In general, the city itself isn’t doing that type of work.

“It’s not a whole big additional cost,” Eugene Public Works Project Manager Ned Nabeta said.

“Overall those costs are pretty minimal compared to a larger project.”

Anatomy of a parking space

Taking a closer look at how the costs for the Tower Theatre parking spaces broke down provides some insights.

Unlike a bill that a homeowner might receive for a handyman’s repair job, Wilson Curb’s invoice combines materials and labor into one line for each component of the job, as is standard practice in the industry, O’Neal said.

The prices are not the actual cost in terms of supplies and work, but rather what the company said in its bid the work would cost. The final bill for the project, including design work done by another company, was about $60,000.

Therefore, there is no easy way to determine what the company actually spent on materials and manpower, O’Neal said.

“The bottom line is, they bid it, we accepted it, they built it,” he said.

For example, the required drains in front of the Tower cost a total of $8,525. Removing old asphalt and laying down new asphalt at the correct grade rang up another $16,290.

And it cost $11,000 to replace all the small sidewalk paving stones around the spaces.

Lou Condley, Wilson Curb’s bookkeeper, said the relatively high prevailing wages that the company was required to pay its employees contributed to part of the high total. For example, concrete masons get more than $32 per hour, she said.

An official from Wilson Curb referred all comments and questions on the Tower Theatre project to O’Neal, who works for the city.

Calls to several local and national companies that sell the individual bits and pieces for the spaces indicate that the materials themselves are significantly less expensive than the amounts shown on Wilson Curb’s invoice.

McNichols Products, a national company with offices in Portland, sells complete 40-foot-long slotted drain kits for about $1,500.

Wilson’s bid — which includes labor costs — charged $8,525 for the job.

Similarly, Traffic Safety Supply Co. in Portland sells 2-by-5-foot bumpy yellow mats, known as detectable warning mats, for $175 each. The amount needed for the parking spaces would have cost about $1,050.

The line for that item on Wilson Curb’s bid — which also included labor — was $5,040.

The invoice charges a total of $300 for material and labor to install four concrete wheel stops, two for each space. Central Oregon Redi-Mix sells the stops for $25 apiece.

It is easy to assume that the balance of the expenses on Wilson Curb’s bid for the project are for labor, but it’s not quite accurate to calculate the math that way, O’Neal said.

“If you were doing a job, and there was a big possibility you’re going to make a mistake, are you going to cover your costs? Absolutely,” he said.

Looking for solutions

City officials are hopeful that they will soon be able to start grouping smaller projects together into larger projects that can attract competition from construction companies on the west side of the Cascades.

Another source of added costs is the outside consultants the city uses for much of the ADA-related design work.

“Us constantly outsourcing design to consultants is the epitome of inefficiency on this,” Councilor Peter Gramlich, who is a home designer, said Wednesday.

Gramlich and other councilors urged city staff to start doing more design work themselves, even if it means creating new positions.

“I think over time, we’re going to get better at this and develop the in-house capabilities,” Transportation Engineering Manager Nick Arnis said.

Meanwhile, despite rain showers and a bit of snow Thursday, city crews continued their work on several of the Mirror Pond parking lot spaces, busting up parts of an old ramp and sidewalk to make way for new ones at the correct grades and dimensions.

The work was originally slated to be complete by the middle of September to meet a deadline the city imposed on itself as part of its regular reports to the U.S. Department of Justice. Related work on parking spaces and curb ramps in the parking lot on Louisiana Avenue next to City Hall has not yet started.