Trained to taste

Published 4:00 am Saturday, November 24, 2007

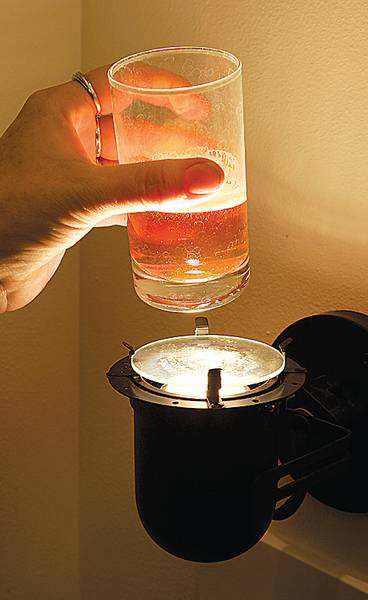

- Color Deschutes Brewery plant sanitarian Kristen Christensen checks the color and clarity of a glass of Inversion IPA to make sure it looks the way an India Pale Ale should.

Good beer is all about the flavor.

Hoppy can be pleasant; so can fruity. Rancid or soapy? Not so good.

Tasty (and not so tasty) brew turns on myriad flavor factors, all contained in the Beer Flavour Wheel, an industry-wide standard that describes 122 smells and tastes associated with brews around the world.

At Deschutes Brewery, “sensory testers” use the wheel and their own discriminating palates to maintain the quality of the beer the Bend company produces.

Tough job.

“This is not all that they do,” assures quality assurance manager Shawn Theriot.

These employee volunteers who gather four mornings a week to taste the distinctive ales, porters, Pilsners, stouts and seasonal brews coming down the line, work other, mostly full-time jobs in the Deschutes Brewery plant.

“Usually, we taste the beer that’s going to be bottled in the next day or two,” says Christina LaRue, who was in charge of preparing the samples for the testers to taste last month.

Before each session, LaRue pours samples of the target beer and spikes some of them with off flavors to keep the sensory testers honest. From behind a panel, she slides the glasses of beer out to the tasters, seated in cubicles before a computer screen. They hold the beer to a light to test for clarity (a little cloudiness is good in craft brews), then smell it, taste it and swallow it. They then note their impressions using a specialized computer program called Compusense.

It’s not something they do without training first. When Deschutes Brewery started the testing program in June 2006, a British company called Flavoractiv conducted a 40-hour, week-long training program, according to training panel coordinator Amanda Benson. Now, with the sensory testing up and running, the panel trains one hour per week, in addition to its beer-tasting duties.

The training has the volunteer testers speaking the same language, Theriot said.

“If I call something acidic and someone else calls it acetic, we have a problem,” Theriot explains.

There’s a universal language of beer that ensures all taste testers are on the same page.

And the wheel’s the deal.

One would expect characteristics such as floral, hoppy, malty and nutty to be associated with fine beer. But catty, mouldy, sulfury or burnt? That’s the downside.

It takes constant practice to get these right.

“It’s important for these guys to get in here and taste daily,” said Theriot. “It’s not like riding a bike. You have to have constant exposure to all of these defects or you get rusty.”

Benson said the relentless tasting and testing has paid off for the company. More than once, the testers have found something in a batch of beer that was subsequently improved.

“They have caught things,” Theriot said. “But we use it more as a proactive tool to correct (taste) trends.”