Winter wonderment

Published 4:00 am Thursday, January 10, 2008

- Winter wonderment

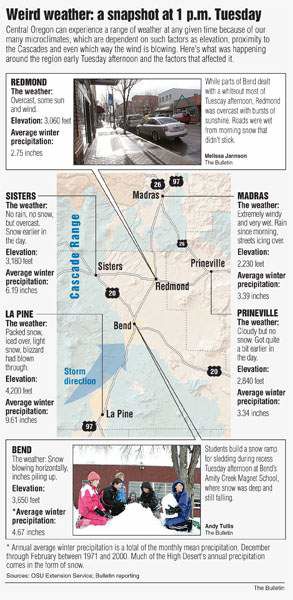

While tiny flakes of wet snow whipped sideways across Bend on Tuesday afternoon, the skies in Redmond were overcast but bright and the streets were bare. “There’s no storm here, just a little wind,” Bud Prince, manager of Redmond Economic Development, said around 1 p.m.

At that same time it was “sloppy” in Sisters, where it had snowed, then rained, then snowed again, said Mayor Brad Boyd. No precipitation was falling at that moment.

“But that doesn’t mean it won’t in another five minutes,” he warned.

Tuesday brought examples of how variable weather can be across the region, even in areas separated by a couple dozen miles or fewer. These microclimates, caused by the distance a place is from the Cascade Range, elevation and other factors, can result in dramatic differences in the weather experienced by area residents.

Bend usually gets more rain and snow than Redmond, for example, and La Pine gets even more than Bend.

“It’s been off and on, nasty to nastier,” reported Rachelle Urbanc, an employee at Gordy’s Truck Stop in La Pine, where it was snowing lightly around 1 p.m. Tuesday. She estimated about 6 inches had fallen, and the snow was packed and iced over, making things “cruddy.”

The snow in Prineville had stopped for the moment, but the cloudy skies made it look like more could fall at any time, said Tish Plasterer at the Crook County Sheriff’s Office.

But in Madras, although it seemed to be snowing all around the city, it was just rainy at Ahern’s Stop ’n’ Shop, reported employee Susan Frolich.

“It’s extremely windy and very wet,” she said. “I’m watching trees bending over right now in front of my store.”

The Cascades factor

When forecasters come to Oregon from the Great Plains, they’re often shocked at how complex the weather is in this area, said Jon Mittelstadt, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Pendleton.

The biggest impact on the amount of rain and snowfall in Central Oregon comes from that big obstacle between the region and the moist air coming from the Pacific Ocean — the Cascade Range.

“It’s a very striking difference,” Mittelstadt said. “Going from the west side of the Cascades to the east side is one of the largest changes you’ll find anywhere on the globe because of the strong Cascade rain shadow.”

What happens is that as air masses hit mountains, whether it be the Cascades or the peaks of the Newberry National Volcanic Monument, the air rises and gets colder, said George Taylor, Oregon’s state climatologist. When air is colder, the water vapor in it condenses and forms clouds and liquid water in the form of rain or snow.

Once the air passes over the crest of the Cascades, however, it descends along with the slope of the mountains.

“And as air descends, it warms up, and its capacity to hold water vapor increases,” Taylor said.

So the water becomes vapor instead of raindrops or snowflakes, making the east side of the Cascades drier.

And the farther east they are of the crest, the drier towns are, he said. While the crest gets around 100 inches of rain annually, Sisters gets 14 inches, Bend receives about 12 inches and Redmond, which is northeast of Bend, only sees 8 inches of precipitation.

The elevation factor

“There’s not that much elevation difference between Bend and Redmond,” he said. “What really matters between Bend and Redmond is the proximity to the mountains.”

Redmond is especially affected by this sinking, dry air because it’s lower in elevation than the terrain in all directions but north, Mittelstadt said.

Even within Bend, he said, areas that are slightly higher in elevation will have more precipitation because of the movements of air.

And La Pine receives more precipitation not only because its elevation is greater than Bend’s, but because the Cascades are smaller to the west of it than they are west of Bend.

Maps of annual precipitation amounts show this effect of the terrain, Taylor said. East of the Cascades, the areas where there are greater amounts of rainfall and snowfall correspond to physical peaks such as Paulina Peak, Steens Mountain, the Ochocos and the Wallowas.

“In general, the higher the elevation, the wetter and the cooler,” Taylor said. And the moisture-filled air masses that come off the ocean lose some of that water as they move east over different terrain.

There’s not much of a difference between the elevation of Bend and Redmond, but oftentimes there’s enough of a gap to make the difference between rain or snow in the two cities, Mittelstadt said.

When there’s a really cold air mass, forecasters know it will snow everywhere, he said. But more often, the snow level is between the 3,000-foot mark, near Redmond’s elevation, and Bend’s elevation of 3,650 feet.

“A typical forecast challenge for us is because that snow level is often right in there,” he said. “It makes a difference between having a rain-snow mix or a good snow that accumulates.”

Knowing the differences between the microclimates can have a variety of uses, Taylor said. It can influence decisions including from what kinds of crops to grow, how much fertilizer to use, when to spray or when to irrigate, and how much runoff culverts are going to have to accommodate, as well as recreation purposes, he said.

Microclimates are good things for gardeners and landscapers to figure out as well, said Amy Jo Detweiler, horticulture extension agent with Oregon State University’s Extension Service in Redmond.

“As you decrease in elevation you’ll end up with a longer growing season and a wider plant palette,” she said.