The lead blanket controversy

Published 4:00 am Saturday, March 1, 2008

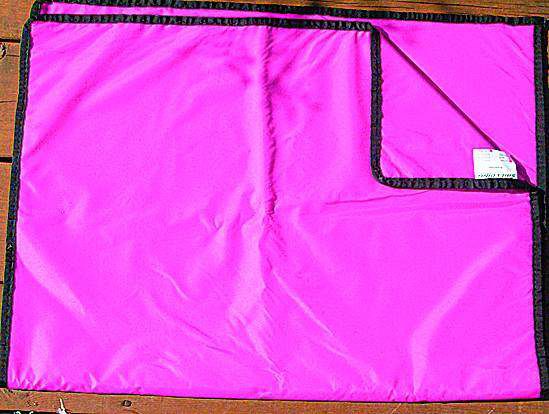

- Photo submitted by Lois Smith

A mother’s desire to help her autistic daughter led her to a Madras company she says sold her a potentially poisonous blanket, above. The company denies her story. The incident has stirred up concern within the autism community and among public health officials.

Lois Smith was looking for information on manufacturing methods of lead-filled blankets when she called Shielding International, a Madras company that makes protective lead clothing for medical and dental use. Instead, she says, the company pitched and sold her a lead-filled blanket for use in a therapy sometimes used for autistic children. Had she used it, she and public health experts say, it could have poisoned her 5-year-old daughter.

The company disputes that it sold her the blanket, putting the blame on a distributor in Michigan. Smith says that, though she did not initially call looking to buy a lead-filled blanket, the company suggested it to her once they found out she had a child who had been diagnosed as autistic.

The possibility that a company would be marketing these blankets has created a firestorm in the autism community and concern among public health authorities.

Two state health departments, a Michigan congresswoman, the federal Consumer Product Safety Commission and the Food and Drug Administration have gotten involved. Though there’s been no disciplinary action against the company and apparently no laws have been broken, the Oregon Department of Human Services recently warned against the use of lead products with autistic children.

“This is the first we’d ever heard of anything like this,” said Richard Leiker, a manager of environmental toxicology at Oregon’s DHS who put together the department’s recommendation. “It could be a very serious hazard.”

Weighted therapy

The issue surfaced when Smith, who lives in a small town in Michigan, was on a hunt last fall to find out how heavy metals had gotten into her daughter Toni’s body and seemingly poisoned her. Toni had been diagnosed as autistic and had gotten a lead-filled blanket from a therapist who was using it for a practice called weighted therapy.

During weighted therapy, heavy blankets are placed over a child to help focus and comfort the child. The therapy is often used in children with autism or other development disorders, said Joyce Burk Brown, occupational therapist at High Desert Education Service District, which provides special education services to schools in Crook and Deschutes counties. “For some children, it’s been essential,” she said. High Desert uses blankets or vests weighted with flaxseed or pebbles, and often hands them out to parents to take home. “There are students that like them so much that it’s hard to get it off them.”

Children sometimes sleep with the blankets, wear them during their daily activities and put them in their mouths, exposing them to whatever is inside. When the blanket is weighted with beans, rocks or sand, as many are, there is little danger to the child. But blankets filled with lead can poison a child, potentially leading to permanent neurological problems or delayed development. For a year and a half, Toni carried hers around and sometimes licked it, before the Smiths realized that it could be harming her.

Looking for answers

Once they figured the blanket could be contributing to the high levels of heavy metals in Toni’s body, Smith began calling all over the country to try to figure out exactly what had happened. Toni’s problem was actually from other heavy metals found on the blanket, and though she did not have elevated blood lead levels, the Smiths had her tested several months after she stopped using the blanket. Smith did not know where the blanket had come from and, in the course of researching that, called the Madras company to find out what other materials they used in constructing their lead-filled blankets and vests.

While there have been many other cases of children who have been poisoned by lead – a 4-year-old Minnesota boy died in 2006 after swallowing a lead charm – there are few, if any, other known cases of a child harmed by using lead products for weighted therapy. However, weighted vests are very commonly used in therapy; one study estimated more than half of occupational therapists had used them. Experts are concerned because, though weighted vests commonly contain no harmful substances, if they do, the children are exposed to huge doses. Also, autistic children are already more vulnerable than other kids.

The dispute

After more than a year of therapy without improvement, Smith had figured out that the lead blanket her daughter was using could be more harmful than helpful. In fact, she had learned by last fall that some of the autism-like symptoms could actually be caused by the heavy metals in the blanket. That’s why, on an afternoon last October, she dialed the number of Shielding International, the Madras company. What happened next is in dispute.

Smith says she began explaining her curiosity about the manufacturing methods used for the blanket. She mentioned she had an autistic daughter, she said. The operator, Smith said, cut her off and asked her if she wanted to buy a lead-filled blanket for use in therapy. They’ve sold them before without complaint, Smith said the woman explained.

“I was just kind of floored when she said that,” Smith said. She hung up the phone without buying the blanket, but kept thinking about it. “I couldn’t hardly sleep that night.”

The next day, Smith’s phone records confirm, she called the Madras company back. Still in disbelief that a company would be marketing lead blankets for children’s therapy, she says she decided to try to buy one to see if she could.

A representative at Shielding, Smith said, took her order and then asked her to call a local distributor to confirm shipping. She called a distributor three minutes after she got off the phone with Shielding, the phone records show. One day later, according to a receipt, she was shipped a Shielding-made hot pink 24-by-36-inch lead blanket.

Shielding International disputes Smith’s story. Susan Kovari, CEO, said, “We did not sell her a blanket, she actually went through a distributor.” Kovari said she did not know how Smith had gotten the number for the distributor, but that she could have called Shielding and an employee would have given it to her. She called the idea that the company would sell blankets for use in weighted therapy “preposterous.”

Kovari also said that the company does not market lead blankets and none is listed in the company’s product line on its Web site. Kovari said she did not know how Smith would have known that the company makes blankets. “Our distributors special-order to get a blanket,” she said. “This was a lady that went out and tried to see if she could buy a lead blanket and she did.”

The distributor that sold Smith the lead-filled blanket, Radiology Imaging Solutions of Grand Rapids, Mich., confirmed that it had sold the product to Smith. Robert Barkema, an owner of the company, said it was not the company’s practice to question customers about their intended use of the product. He said after taking her order, the company called Shielding to make sure they were ordering the correct product. “We thought we were helping her out.”

Spreading the word

After receiving the lead blanket, Smith contacted both the Michigan and Oregon health departments about her experience. Sharon Hudson, a program coordinator for the state of Michigan’s Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program, called the company in November.

“I wanted to make sure we were using something other than lead with something that was going to be used by kids,” said Hudson. “We’re trying to get lead out of child products and to be encouraging the use of lead seems to me to be very poor practice.”

Hudson said that when she called Shielding to ask about lead blankets for use in weighted therapy, she was told that the company sold those products. Hudson said the representative from Shielding, who she said was named Carol, told her to send two of the child’s own blankets to the company, so that they could fill them with lead and send them back to her. “We talked for quite a while,” Hudson said.

According to Hudson’s notes, the conversation went like this:

“Is that a good idea to have around kids?” Hudson asked.

“They won’t pick it up and eat it,” Carol replied.

“I’m not sure it seems like such a good idea.”

Carol replied, “Well, then, discuss it with your doctor.”

Hudson did not purchase one of the blankets.

Kovari disputed Hudson’s version of events.

“Our representative recommended that she not only seek medical advice regarding use, but that she consider obtaining a blanket made of non-lead materials,” Kovari said. She said the company’s representative did not tell Hudson that the company made lead blankets for use in therapy and that the representative did not suggest that Hudson send in two blankets.

What’s next?

Leiker said DHS did not have the authority to take disciplinary action and, because the hazard is unique and relatively rare, he was not aware of any regulation. His primary concern, he said, was making sure that no Oregon children were using lead-filled vests. “We’ve talked to the various people who have tried to deal with this and tried to get the word out.”

Leiker posted a warning on the state’s Lead Poisoning Prevention Program Web site. Shielding updated its Web site last week, Kovari said, and now links to a series of lead alerts, including one on the hazards of using lead blankets in therapy.

Leiker said he contacted the state’s dental association to inform their members not to recycle old dental vests for autistic children, and also sent word to state schools to warn therapists of the danger.

The regulation of these types of products falls into a gray area not covered by state or federal laws.

The Consumer Product Safety Commission, which Smith said she called, passed the case to the FDA because, the CPSC said, it fell under that agency’s jurisdiction.

However, it’s not clear if the FDA has the power to regulate the product, either.

“If manufacturer makes a medical claim, then it needs to be approved or cleared for marketing by FDA,” said Pepper Long, a spokeswoman for the federal agency. But because lead-weighted blankets are not typically used, nor is there solid evidence that they are marketed, for therapy, a so-called off-label use, they are not currently regulated by the agency for that purpose. The FDA did not comment on this specific case.

In fact, unlike many medical devices, anyone who wants one can buy a lead-filled blanket or apron, said Barkema at Radiology Imaging Solutions. “We have no reason to ask what somebody is using it for. There’s no laws,” Barkema said. “Anybody that wants to can buy one of these things.”