Crooked River Ranch and its pets – on edge

Published 5:00 am Sunday, March 16, 2008

- Crooked River Ranch and its pets - on edge

CROOKED RIVER RANCH —

Lana Urell still can’t understand why Moxie died.

The 4-year-old golden retriever started shaking Dec. 12 as the family looked on in horror. Moxie turned rigid, fell to the ground and died within two hours at their Crooked River Ranch home, said Lana’s mother, Marae Urell.

She recently gave Lana, 7, a new dog. But to this day, Lana still carries a photo of Moxie in her school backpack. The family has no proof, but they believe Moxie was poisoned.

“Moxie was one of our family members,” Urell said. “And it was right before Christmas … How do you explain to your 6-year-old that it wasn’t a natural death? She keeps asking, ‘Why would somebody do this, mommy?’”

Moxie is one of at least 10 dogs who people suspect have died from poisoning in Crooked River Ranch in the past year and a half — and several cases have been confirmed as strychnine poisoning. Officials have yet to catch anyone and say they don’t have any suspects.

The pet deaths are occurring in a rural community where many neighbors live relatively close to one another in one-story homes. Folks know their immediate neighbors among this loose collection of rural lots where deer regularly roam. And for the people who choose to live on this ranch because they want wide-open spaces for their dogs, these poisonings have posed unanswered questions.

“To have it happen to us is kind of surreal,” said Chris Garner, 32, whose own dog survived poisoning. “We’ve got an acre at least out here. We used to let our dog run around, and other people let their dogs around. There’s like three or four different dogs that run through our properties — and that’s how we like it. … But now, it’s just really kicked into gear, and we’ve gotta get the fence up.”

A second wave of tragedy

Crooked River Ranch is an unincorporated community northwest of Redmond with about 4,000 people who live in open spaces nestled between the Crooked and Deschutes rivers.

Many who live here reside along dirt roads that snake by ancient junipers and rusting cars. The howl of dogs often disturbs this otherwise silent place.

Garner said folks have moved here from the Willamette Valley and California in hopes of escaping a concrete jungle for a rural oasis, and had allowed their dogs to roam freely.

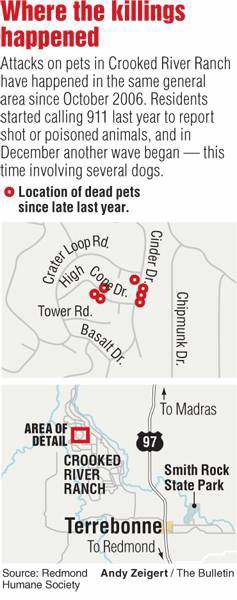

But in October 2006, ranch residents started reporting sick, injured and dead pets.

Callers to 911 said a variety of animals had been shot or poisoned. A reward of $200 quickly climbed to $5,000 as people rallied to find the culprit.

In the Crater Loop Road area, at least four dogs and several cats were shot, along with a pet duck and a rabbit. In addition, at least two dogs, one cat and three rabbits died with symptoms related to poisoning.

The cases varied.

A bullet shattered the left back leg of Kiara the cat. Reggie the tabby bled from the mouth and then died from rat poison. Koko the Pomeranian got stitches in his intestinal tract after getting shot by a pellet gun.

Jefferson County sheriff’s deputies arrested a Crooked River Ranch man in April 2007 on suspicion of several poisonings, but prosecutors never filed charges.

The deaths slowed down for a while — but then began again this past December, said Josh Capehart, an animal welfare officer with the Humane Society of Redmond.

Losing Bailey

After getting off a firefighting shift around 9 a.m. Dec. 6, Eric Stafford came home to feed the horses and play with his dogs.

Stafford threw sticks to Bailey, a 4-year-old McNab, Odie, a 4-year-old Australian shepherd, and Tanner, a 3-year-old red heeler.

When he walked back inside, Stafford noticed Bailey was “kind of lagging.”

Suddenly, she went into a seizure.

“Her legs all went rigid,” the 35-year-old said. “She stiffened up. She literally was stiff and fell over. Her tongue would fall out, and her eyes would roll in the back of her head.”

Stafford took Bailey to the Terrebonne Veterinary Clinic twice that day, but she died on the front seat of his truck on the way to her second visit.

When Stafford returned home, he walked through the yard and saw a deer carcass lying by the last stick he threw to his dog.

Stafford started working with Capehart to catch the culprit. Stafford said the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office wasn’t doing much.

He called the Sheriff’s Office from the vet and was told somebody would head out to the ranch, but nobody came.

“The sheriff’s department wasn’t gonna do it,” Stafford said. “And I’ll be damned if we let this person get away.”

Jefferson County Sheriff’s Detective Sgt. Bryan Skidgel said Capehart, who has responded to every call that has come in, has taken the lead on the investigation.

“I don’t know of anybody who hasn’t been contacted,” Skidgel said. “I mean, a dog is man’s best friend, and we take that seriously.”

The investigation

Capehart said seven dogs have unexpectedly died on the ranch since December.

“They were all unexplained deaths basically with seizures,” he said.

Capehart, who has been an animal welfare officer for eight years, said the incidents are highly unusual.

“I haven’t had reports from anywhere else in Central Oregon with dogs getting poisoned,” he said. “It’s an odd thing to have this many incidents in one area.”

One dog survived because its owner rushed to the Terrebonne Veterinary Clinic at the first sign of poisoning.

Dr. Allyson Horton practices at the clinic and said she has seen one dog that died after being poisoned.

Vets at her office also saved another dog that was showing symptoms of poisoning. The dog was given hydrogen peroxide, which caused it to vomit. Then it was fed charcoal to absorb the poison.

The animal lived, likely because it hadn’t eaten much poison, Horton said.

When he caught wind of the apparent poisonings late last year, pesticide investigator Mike Odenthal of the Oregon Department of Agriculture decided to get involved. Odenthal’s agency regulates pesticides and investigates possible misuse.

On Friday, lab results came back from testing the contents of two of the dead dogs’ stomachs.

“Both were positive for strychnine,” he said.

The poison is sold over the counter and generally used to kill burrowing rodents common to Central Oregon.

Odenthal suspects the strychnine might have been baited or mixed with something animals like to eat, because it is extremely bitter. The last dog that died appeared to have eaten part of the stomach of a dead deer, Capehart said. The dog had ingested haylike material mixed with small green pellets contained in the deer’s stomach, found near the deer’s carcass.

“The question becomes now, was the deer used as bait and the strychnine laced in the meat, or did the deer eat the strychnine and die?” Odenthal said.

Some on the ranch don’t appreciate deer eating their landscaping and gardens, according to Capehart.

“Out at Crooked River Ranch, it is totally overrun with deer,” he said. “You can’t hunt there or anything like that at all, and we have had complaints and people asking how to keep the deer out of their yard.”

Jefferson County Dog Control Officer Renee Davidson said she is working to ensure that no other dogs die by handing out tickets to anyone with a dog at large.

“We’re going to be citing people and taking the dogs,” Davidson said. “The cite is $250, and then they go to the Jefferson County impound, and it’s between $40 and $60 for the impound, and $12 a day. If they don’t have their tags, it’s another $750.”

Davidson said she, too, has heard the complaints about deer roaming free in the area and wouldn’t be surprised if someone was targeting them.

“I absolutely think someone would poison them,” she said.

The response

Jefferson County Sheriff Jack Jones said his deputies have increased patrols to the extent that they can, given short staffing.

“And I’ve got two who live on the ranch, so they start and end their shifts there,” Jones said.

He said two reserve deputies live on the ranch as well, and his full-time staffers have take-home patrol cars.

“We’re trying to get a handle on what we really have going on out there,” Jones said. “One dog dead is too many.”

Some residents have started taking the law into their own hands. They’ve set up cameras, passed out fliers and kept an eye on each other’s yards.

“We just patrol our properties,” Urell said. “We look out for anything suspicious.”

But that doesn’t seem to help, said Todd Mettleton, 47, who has lived in the area for about eight years and has not had any of his own pets get sick.

Mettleton said he looks for any strange activity but never catches anyone.

As a result, residents have few options but to remain on guard.

‘Like a ghost town’

Lori Palm, who was born in Portland and moved to the area about three years ago, said she felt a somber mood spread on the ranch after the December deaths on High Cone Drive. Before the poisonings, dogs often roamed the streets and played with each other. After those incidents, residents kept their dogs indoors.

The barking stopped.

“It was like a ghost town,” Palm said.

Even today, she keeps a sharp eye on Chinook, her 4-month-old chocolate Lab and Rottweiler mix that replaced Cody, an almost 4-year-old chocolate Lab that she said died in December from poisoning.

When Chinook bounded across her yard too far on Thursday, Palm immediately called him back.

“He’s never been outside the gate,” she said. “We have to watch him 24/7.”

Jessica Garner, a Southern California transplant, has lived in the ranch for about three years and got her black Lab, Tasha, about 10 months ago. She takes no chances.

“I don’t even walk (my dog) on the street anymore,” Garner said. “I just drive her to the park.”

“We just don’t take her for walks anymore,” she said. “You have to be careful.”

And Stafford, who plans on helping Capehart investigate these deaths, remained on the alert Thursday afternoon when Missy, a 4-month-old McNab that has replaced Bailey, started choking.

Stafford grabbed Missy, wrenched her mouth open and checked to see if there was anything strange inside.

Nothing. A false alarm.

But for a moment, Stafford said, he relived Bailey’s death.

“I took it as a personal attack.”