Body fat monitors show the big picture, but skimp on accuracy

Published 5:00 am Thursday, May 15, 2008

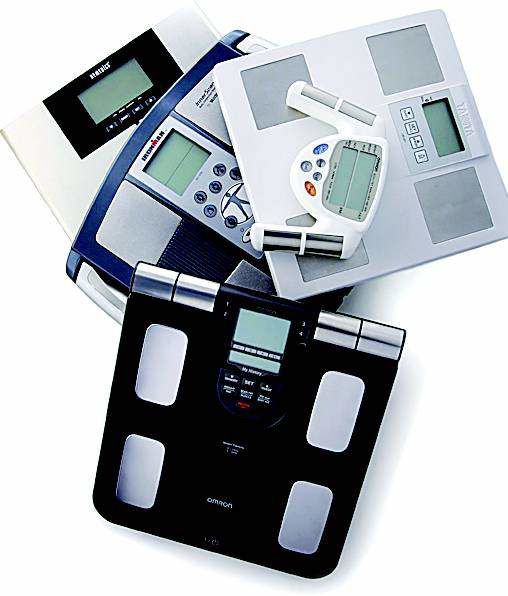

- Body fat monitors can range from $30 to nearly $300.

WASHINGTON — Depending on which Japanese conglomerate you believe, either I have the body of a 25-year-old or I’m pushing 70. Which is disconcerting either way, because I was a mess when I was 25, and I’d prefer to let 70 wait its turn.

But according to such companies as Omron and Tanita, my “metabolic age” lies at one of those extremes.

Rise of the machines

“Metabolic age” is a statistical construct that, along with other bells and whistles, is being built into the “body composition” monitors proliferating on store shelves. There are a good half-dozen or so of these machines on the market now, with prices from about $30 to nearly $300. Their main purpose is to measure body fat.

They use a technology called bioelectrical impedance, which passes a small current through conductive foot pads or handheld electrodes. The current can pass easily through water-rich muscle fiber, but it bogs down in fat. Based on how much of the current gets through, the machines use mathematical models to estimate the amount of fat that got in the way en route.

Not content with that statistic, however, competing companies have begun loading their machines with lots of other stuff: estimates of how much muscle you have, how many pounds of bone, the amount of “visceral fat” around your vital organs, how many calories you need to eat in a day, and, based on all of the above, how “old” you are.

Which prompts the question: If the age estimate by two monitors can be so divergent, what about the rest of the stuff the machines are supposed to measure?

Comparing methods

To get a sense of the accuracy of retail-grade monitors, I got five models from three companies and matched them against two clinical methods: a hydrostatic “dunk tank” test often used in research and the hand-calipers pinch test often performed in health clinics and gyms.

The two clinical measures, taken by doctoral student Andy Ludlow at the University of Maryland, raised a point that representatives for the monitor companies like to emphasize: Even accepted standards such as the dunk tank, which uses formulas related to the displacement of water and the comparative density of muscle and fat, are still only estimates.

By the numbers

The dunk tank put me at just under 21 percent, a bit higher than it should be, while the pinch test registered 18 percent, well within the recommended range.

Company representatives are generally careful to say that their machines should be used more to establish trends than for precise measurements.

The devices, in other words, will give you a rough sense of where you stand but are better used to see whether your body fat percentage is going up, down or staying steady over time. From that perspective, the monitors — two from Omron, two from Tanita and one from Homedics — came reasonably close to Ludlow’s estimates. They ranged from a low of 18 percent (Tanita’s higher-end Ironman Innerscan model) to a high of 20.9 percent (Tanita’s less expensive model UM061). The two Omron models came up with similar numbers: 20.7 percent from the more-expensive Full Body Sensor and 20.1 percent from the company’s low-cost HBF306 Body Logic. The Homedics 540 Health Station was the outlier, putting me at a whopping 29 percent fat.

Given all the caveats, I wonder how much value the machines really add. If you’re attracted to technology and like to quantify things, this is a reasonable purchase. But here’s an alternative: Contract your abs and grab your belly. Anything in your hands doesn’t need to be there.