A brother lost, a brotherhood found

Published 5:00 am Saturday, May 31, 2008

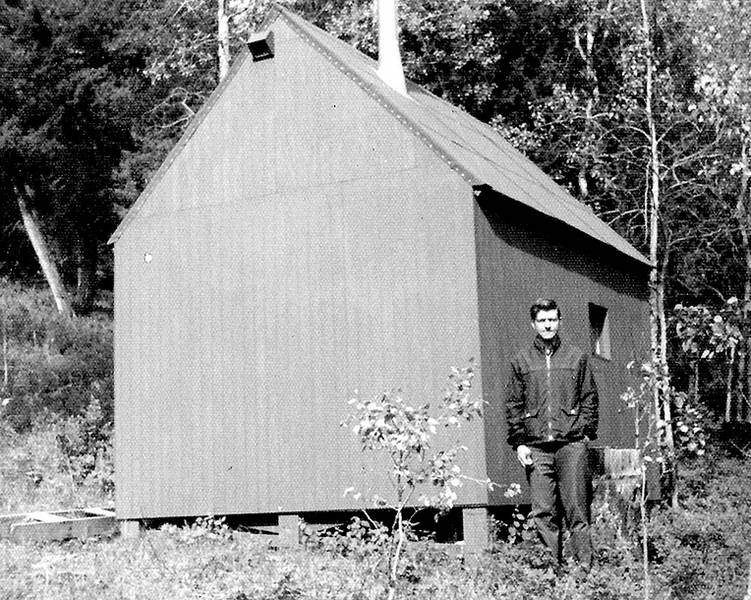

- The Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski, stands outside his cabin near Lincoln, Mont., in June 1972. To avoid the death penalty for his crimes, Ted pleaded guilty in exchange for a life sentence.

The two brothers hiked high into the Montana wilderness, cooked beans beneath the stars and talked like they hadn’t in years.

By a campfire outside his one-room cabin, Ted read to his younger brother from a book on Roman history. For a time, they were just kids again, Teddy and Davy Kaczynski from Evergreen Park, Ill.

Gone was Ted’s long-festering animosity toward their parents, or at least any mention of it. He had sent venomous letters accusing them of not loving him, blaming them for his social awkwardness.

But his brother’s visit had gone so well that Ted even considered traveling to Dave’s own retreat in southwest Texas. On their last day together in the fall of 1986, though, Ted declined.

“I just really don’t have the time to come and visit you, Dave,” he remembers Ted saying. “I have too much to do.”

Dave was perplexed. Ted’s life in the woods didn’t appear to hold many obligations.

What Dave didn’t know was that his brother, from his remote cabin near the Continental Divide, had been waging a bizarre eight-year campaign of terror. Constructing bombs from fertilizer, razors and screws, the man dubbed the Unabomber already had killed one person and injured 27 more.

Ted’s rebuff of Dave would mark the beginning of the end of their brotherhood. Not long after Dave’s visit, in his next brutal attack, Ted unwittingly would spark the beginning of a new bond.

Through an improbable chain of events, that victim would forge a lasting connection to Dave, becoming his confessor, friend and ally.

Interviews, rare access to letters and Ted Kaczynski’s unpublished writings offer a new perspective on the Unabomber and his relationship with his family, including the sibling who turned him in. Thirty years after Ted planted his first bomb in Chicago, a story emerges of brotherhood lost and found.

Ted and Dave

Ted beckoned Dave to the door. It was a summer day in 1952 on South Lawndale Avenue in Evergreen Park. Three-year-old Dave had once again shouldered his way out the back door, only to find he wasn’t tall enough to reach the handle to get back in.

But this day he found Ted, 10, fiddling with the screen door. In one hand, his brother held a spool of thread from their mother’s sewing kit; in the other, a hammer and nails from their father’s toolbox. Dave watched as Ted unwound the thread and hammered the empty spool into the wooden screen door.

It dawned on Dave what Ted had done. He had devised a makeshift doorknob, about chest-high, for Dave — an emblematic act of kindness from his protective older sibling.

The Kaczynskis had moved to Evergreen Park from Chicago’s Back of the Yards neighborhood, partly to escape the claustrophobia and danger of urban life. The boys’ father, Ted “Turk” Kaczynski, was a sausage maker who passed on his love of the outdoors to his sons.

He and his wife, Wanda, also wanted better schools for their sons. Though Turk dropped out of high school to help his parents during the Great Depression, he and Wanda put great value on education. And both boys excelled in school; each graduated early from high school and went off to the Ivy League.

When Ted was in fifth grade, a school counselor gave him an IQ test, and he scored a 167, well into genius territory. The counselor told Wanda that he could be “another Einstein.” In junior high, he was correcting his algebra teacher. As he progressed academically, though, Ted withdrew further into books, into himself. His intelligence only exacerbated his lack of social skills.

Dave revered Ted, but even at an early age he recognized Ted’s nervousness, his suspicion of people. In a book Dave is writing, he recounts asking his father as a young boy: “Dad, what’s wrong with Ted?”

“How do you mean?” Turk said.

“I mean, he doesn’t have any friends or anything,” Dave said. “He doesn’t seem to like people.”

“Dave,” their father said, “you have to understand that your brother is very intelligent. He has different interests from most of the other boys and girls his age. But in a few years he’ll go to college, where he’ll find people who are interested in the same things he’s interested in. Some day he’ll fall in love and get married, and have a family of his own. He’ll find himself. He’ll be OK. You’ll see.”

‘I’ll fire you if you don’t stop’

In the summer of 1978, the Kaczynski brothers found themselves at their parents’ new home in Lombard — Dave after graduating from college and working various jobs in Montana, Ted after a failed academic career and establishing his mountain retreat outside Lincoln, Mont.

Ted’s homecoming proved dark. He started at the same foam-cutting factory where his father and brother now worked. He briefly dated a female supervisor at the factory, but the woman cut off the relationship after a few dates. Ted responded by posting crude limericks about her around the factory.

Dave approached his older brother in a storage room off the factory’s main floor. He wanted to be discreet.

“You better stop, or I’m going to kick your ass,” he recalled telling him. “I’ll fire you if you don’t stop.”

Dave, who worked part time as a night supervisor, confronted Ted in the storage room. It was a turning point in their relationship.

“He looked at me as a friend,” Dave recalled, “and by the time I got done speaking to him, he was all shut down.”

The next day, Ted walked up to the machine where Dave was working and posted another insulting poem.

“Are you going to fire me now?” Ted defiantly asked.

Heartbroken, Dave replied, “Yes, Ted. Go home.”

Ted did, shutting himself in his room for days. Dave worried he had forced some sort of “psychological break.” Though Wanda recognized some of Ted’s symptoms as possibly schizophrenic, this was a time when little was known about mental illness and even less discussed openly.

Ted eventually knocked on Dave’s bedroom door and handed him a letter. “I’ll show this to you, only on the condition that you don’t discuss this with me,” Ted said.

It was a note Ted intended to send to the woman, explaining himself. It was an apology, of sorts, but it also contained the disturbing claim that Ted was so enraged that he had waited in the woman’s car with a knife, planning to mutilate her. In the end, Ted wrote, he couldn’t do it.

Attacking someone face-to-face proved too much for him. Ted already had established his method of violence just a few weeks before: In May of 1978, he planted his first bomb, which injured a Northwestern University campus policeman who later tried to open the package.

Another victim

In February 1987, Gary Wright never saw the man in the parking lot, but his secretary did. She noticed him through the rear window of the Wright family computer company in Salt Lake City. Behind a pair of aviator sunglasses, his face was expressionless, thin, with a reddish flush and rough-looking complexion, she would later tell investigators.

His hands, whiter than his face, had long, thin fingers. His fingernails, she noticed, were clean. Dressed in a gray hooded sweatshirt, he knelt and placed something in the parking lot, just a few feet from where she stood.

Arriving for work that February morning, Gary Wright noticed the object: a nail-studded piece of lumber. In retrospect, he thought, the nails should have served as a warning. They seemed unnaturally shiny, jutting from the scrap of wood.

But he didn’t want anyone to puncture a tire or a child to get hurt. Students walked through his parking lot every day.

Gary bent down. As he picked up the wood, he heard a click.

He didn’t hear the explosion.

A single nail shot up through Gary’s chin, piercing his lips and ricocheting off his sunglasses, barely missing his left eye.

The blast liquefied nails and razor blades from the bomb, turning them into corkscrew-shaped shrapnel that tore into Gary’s body, searing shut one artery and severing a nerve in his left arm.

The explosion flung Gary back 22 feet as power lines above him convulsed in a wave pattern. Debris and duct tape spiraled down from the sky like confetti.

Horrifying connection

Dave Kaczynski’s wife, Linda, was the first to make a connection. Vacationing in Paris, she spotted a series of newspaper stories on the Unabomber that presented the serial killer as an anti-technology zealot. Linda couldn’t help but see parallels to her brother-in-law.

Dave studied the Unabomber’s manifesto, and his stomach sank. The words “cool-headed logicians” stopped him. Ted used that phrase.

Rummaging around to find family letters, Dave compared them with the language in the manifesto. “Maybe there’s a 50 percent chance that he’s this person,” he concluded.

Dave didn’t know what to believe. How could this figure he once idolized, who looked after and encouraged him, how could Ted become a killer? Had Dave been blinded by family love? Could he have grown up in the presence of evil and not known it?

Soon after, in January 1996, Dave contacted the FBI through an attorney.

For weeks he showed agents letters Ted had written to their family and traveled with the agents to interview people Ted knew. He still held out hope that his brother was innocent, but that hope quickly evaporated when Dave got a call from his FBI liaison. The agent said she was sorry, but Ted had moved to the top of the suspect list.

Less than a week later, Ted was arrested.

Ted’s arrest had left Dave with an urgent need: to know what his brother’s victims or their families were experiencing.

Dave Kaczynski met Gary Wright on the telephone. When Dave dialed Gary’s number, the voice on the other end of the line put him at ease almost immediately.

“Dave, this one’s not on you,” Gary said. “You didn’t do this. It isn’t your fault. You’ve got to let it go.”

“In a rational sense, I know that I didn’t do anything wrong,” Dave said. Yet he couldn’t escape the need “to hear some voice from among those people to say, ‘You’re OK, we don’t hate you.’ Something like forgiveness.”

To avoid the death penalty, Ted pleaded guilty in exchange for a life sentence without parole. At his sentencing hearing in federal court in Sacramento, Dave and Gary ended up on opposite sides of the courtroom. A gulf separated the room — victims and victims’ families on one end, Dave alone on the other, surrounded by media. Ted never turned around to look at his younger brother.

It was the first and last time all three men were in the same room.

As he took the stand, Gary spoke to Ted directly. “I do not hate you. I learned to forgive and heal a long time ago,” he told him. “Without this ability, I would have become kindling for your cause.”

Gary then turned to Dave. “I would like to publicly thank David Kaczynski, his wife Linda and his mother for their extraordinary act of courage. … Without their honesty, integrity and ability to do what was right, Ted would still be in a position to kill or maim additional innocent victims.”

‘Blood brothers’

Gary and Dave’s friendship developed in encounters both searing and small. While traveling in 1999, Gary stayed with Dave and Linda at their home in Schenectady, N.Y. By coincidence, it was Dave’s 50th birthday, so Gary attended the party, and the pair later went canoeing on some of Dave’s favorite streams in the Adirondack Mountains.

On the night before Sept. 11, 2001, Dave was across the street from the World Trade Center for a business meeting. The next day, after the attacks, Dave went home to an empty house. (Linda was visiting family in Chicago.) He could stand neither the TV images nor the silence. The personal echoes — terrorism to advance a warped ideology — were too much.

Then the phone rang. It was Gary. He knew Dave went into New York City for his job and wanted to make sure he was safe.

“My God, he was almost killed by my brother … and here he is calling me,” Dave recalled. “It meant the world to me.”

In the ensuing decade, he and Gary have lobbied against the death penalty and logged thousands of miles telling their story of forgiveness at high schools, colleges, state legislatures, to anyone who would listen.

Though his actions drew them together, Ted is not always the topic of conversation. For stretches at a time, Dave and Gary are just two friends on a road trip.

Dave and Gary sat in the spare breakfast nook of a Holiday Inn Express last spring, a study in opposites.

Gary is shorter and more compact, with the lean frame of a cyclist. He’s louder, quicker to laugh. Dave is tall, graying and soft-spoken, with a slight limp from a hip injury suffered during a softball game.

Last year, their journey of reconciliation took them to an anti-violence conference in Connecticut. Such conferences can seem like a macabre gallery, a collection of people sharing horrific stories: the loss of a child, a spouse, a parent to unspeakable crimes.

Dave is a celebrity here but also a rarity, someone related not to a victim but a killer.

This particular conference proved especially tough on Dave. That same week, Virginia Tech student Seung-Hui Cho killed himself and 32 others in the worst school shooting in U.S. history. Like Ted Kaczynski, Cho sent the media a rambling manifesto. News programs started to call Dave.

Sitting in the hotel lobby, he and Gary talked about their friendship.

“Nobody could take the place of my brother in my heart,” Dave said, “and that’s a very painful place.”

In a book they’re writing together, Dave expands on the notion: “Gary and I are ‘blood brothers’ in a literal sense. Our bond forged through violence is as powerful and as deep as any genetic bond. … I find a poetic balance in having gained a new brother in Gary.”

He wonders if Ted would understand. “Maybe he’d see my relationship with Gary as one more betrayal,” he said.

As they chatted, others attending the conference joined them. A television behind them showed clips from Cho’s video manifesto, and the talk turned to the subject of evil.

As a Roman Catholic, Gary feels that deeds are evil, not people.

As a Buddhist, Dave sees evil as “the absence of light, the absence of hope.”

“Ted had no hope; he was isolated,” Dave said. “His schizophrenia, this cancer of the mind — he was lost to us.”

His brother was able to kill people, he thinks, by stripping them of humanity.

“I’ve always thought — and I might be wrong — that my brother couldn’t have shot someone from across a table,” Dave said.

Klaas interrupted: “But he did kill people.”

The gathering fell silent.

“Ted was not evil through and through,” Dave said. “He was someone, at the very least, who loved his little brother.”