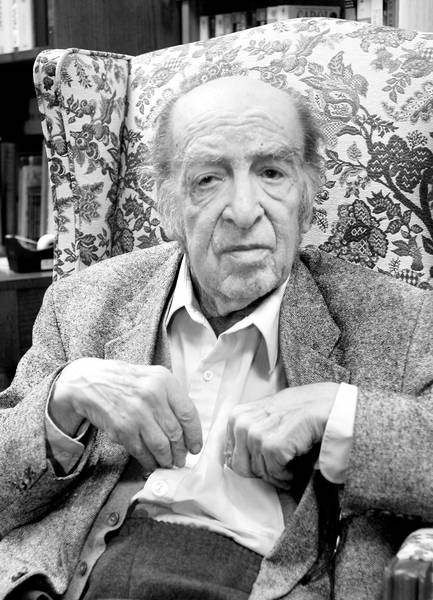

Leonid Hurwicz, 90, was oldest to win Nobel Prize

Published 5:00 am Thursday, June 26, 2008

- “There were times when other people said I was on the short list, but as time passed and nothing happened, I didn’t expect the recognition would come,” Leonid Hurwicz said of receiving the Nobel Prize in economics. Hurwicz died Tuesday at age 90.

MINNEAPOLIS — Leonid Hurwicz, who shared the Nobel Prize in economics last year for developing a theory that helps explain how buyers and sellers can maximize their gains, has died at age 90, a spokesman said Wednesday.

Hurwicz died Tuesday of natural causes, said Mark Cassutt, spokesman for the University of Minnesota, where Hurwicz was an emeritus economics professor. Hurwicz had been in a Minneapolis hospital and had been on kidney dialysis, Cassutt said.

Hurwicz was given his prize in Minneapolis last December because he couldn’t make the trip to Stockholm. At age 90, he was the oldest person ever to win a Nobel, according to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

He shared his prize with Eric Maskin, a professor at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, N.J.; and Roger Myerson, 56, a professor at the University of Chicago.

The award was announced last October, and Hurwicz said he was surprised to win.

“There were times when other people said I was on the short list, but as time passed and nothing happened, I didn’t expect the recognition would come because people who were familiar with my work were slowly dying off,” he said.

In its announcement, the academy said the three “laid the foundations of mechanism design theory,” which plays a central role in contemporary economics and political science.

Game theory

Essentially, the three men, starting in 1960 with Hurwicz, studied how game theory can help determine the best, most efficient method for allocating resources, the academy said.

Hurwicz’s work was theoretical, Myerson said. But it could be explained under the framework of today’s soaring gas prices: If gas prices have gone up because a big producer has secret information on oil supply, and keeping that information secret allows the producer to make more money, the producer would have no incentive to communicate that information to everyone else, Myerson said.

“Before, economists just thought about the prices and tended not to think so much about the planners,” Myerson said. Hurwicz “worked to rebuild economic theory from the ground up based on a view that what markets do is communicate information … that incentives to communicate were what we needed to study, under any system — capitalism or socialism.”

Hurwicz began teaching at the University of Minnesota in 1951. University President Robert Bruininks says he was “an extraordinary man” who left “a proud and lasting legacy.”

“Not only were his economic theories groundbreaking, but he was a renaissance scholar, with a keen interest in many disciplines, an incisive mind and quick wit and a natural grace that endeared him to so many people,” Bruininks said in a statement.