Extreme green living?

Published 5:00 am Wednesday, July 16, 2008

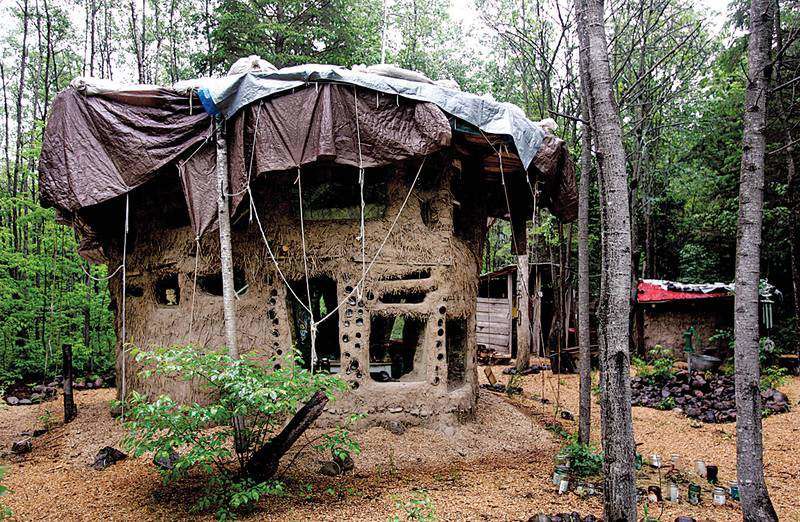

- Machel Piper and Febe Danciers 5-acre property in Winter, Wis., includes a cob house, two storage buildings, a well, paths and gardens. Although the friends still purchase many of their goods from stores, they hope to become more self-sufficient on their property. They live in the house without electricity or running water.

WINTER, WIS. — Machel Piper and Febe Dancier pored over books at the table in their rural home, silently reaching for a shared spoon in a dish of pasta and organic vegetables. Outside, rain drilled the ground from the gray sky. Thunder rumbled.

Inside their snug home, one of five cats nosed close to the meal they had simmered on a wood-burning stove. Dancier reached for tweezers, plucking a tick near the pale calico’s eye. She tossed the offender into the inferno of a nearby candle, the only light in the earthen and straw “cob” house the best friends built two years ago.

Is there a person alive who hasn’t considered, if only for a moment, chucking it all, going off the grid, dropping out of society? Some do.

But few go as far as Piper and Dancier went. Their quest to get quite literally back to nature is a foray into extreme green living that created a home a hobbit could love.

It also revealed that although neighbors, inspectors, officials and the rest of society will bend quite a ways in respecting the idea that a woman’s home is her castle, ultimately, they have their limits.

“We just wanted to get connected to Mother Earth again,” said Machel (pronounced mic-KALE) Piper. “This is just basically a place for us to heal and grow.”

Going off the grid

Their outdoors experience had amounted to some hiking and a little backyard camping. But in December 2005, the duo bought about 5 acres of woodland a few miles outside of Winter, Wis., for $7,500. Piper, 32, had just ended a five-year marriage. Dancier, 29, was trying to rebound from some health problems. She was descending slowly into deafness and sought solace in alcohol. Her natural foods store in Elkhart Lake, Wis., closed.

“I was very lost,” Dancier signed as Piper interpreted. “I was very lonely, so I tried to buy happiness with new clothes, a big house, a new car. I did everything I could to avoid healing.”

The women ceased communication with their parents and half siblings, although the families know where they are. Friendships were left behind. Treasured musical instruments were sold off. Belongings were junked at the curb.

They moved into a van parked on their lot in Wisconsin, laboring under an unforgiving sun, shivering through frigid nights, often wondering: Should we give up?

Even for self-described “earthy” vegetarians, it was a crazy and naive notion, they admit now, to reach into the Earth and build a cob house using their hands and feet. To bid adieu to modern conveniences — plumbing, electricity, a flushing toilet.

“I was scared out of my mind,” said Piper, a former kindergarten teacher. “There was a lot of, ‘God, I just don’t know what we’re doing.’”

Building technique

The cob building technique does not employ what Midwesterners might assume would be corn cobs. It involves mixing clay, sand, earth, straw and water. It is used all over the world, from Africa to England, where the term “cob” means “lump” or “rounded mass.” Some say it has been around since medieval times.

“It’s practical, and it’s beautiful,” said Nathan Ramser, a spokesman for Cob Cottage Co. in Coquille, which teaches workshops on natural building and ecological living.

Ramser estimates that there are 100 cob homes in the United States, many outfitted with electricity and plumbing.

For six grueling months starting in summer 2006, Piper and Dancier mixed the building materials with their feet and molded the structure by hand. There is no framework. Glass was scavenged from dumpsters for windows.

“You have to respect what they’ve accomplished,” said area resident Jerry Dezotell. “Who wants to work that hard these days?” He and his wife, Linda, sold them firewood, donated supplies and befriended the women.

Bumps in the road

Not everyone was so welcoming. As their 175-square-foot house evolved, a neighbor’s seemingly innocent questions came just before a call to the Sawyer County zoning and sanitation department pointing out the women had failed to get a building permit. Their land is situated in a conservative pocket of north-central Wisconsin dotted with million-dollar vacation homes.

It seemed Piper and Dancier’s plan could crumble just as the house neared completion.

Acting on the anonymous tip, county zoning administrator William Christman visited the property on Oct. 2, 2006.

Each of the women was cited for failing to get a land use permit and a sanitary permit. The $1,962 fine was a debilitating blow.

The house also failed to meet the county’s 500-square-feet requirement, an expansion Piper and Dancier said was impossible to complete in one summer.

Their fight landed them in court. Guilty verdicts were handed down. A warrant was issued for Piper’s arrest, although she said when an officer came to serve it, he opted to let it go.

But the stress of struggling with county officials melted away as they slipped down their sawdust trail winding through ferns and trees bedecked with wind chimes and dream catchers.

“The air is so fresh here. It’s so clean here,” Dancier said. “I feel very rich.”

Daily life

A purposely low and narrow Dutch door leads into the cozy home fitted with a lofted sleeping space. A 5-gallon plastic bucket topped with a conventional toilet seat serves as their “humanure,” an eco-friendly toilet filled with sawdust that is emptied daily.

The refrigerator: a hole in the ground topped with a wooden plank. The sink: a wash basin beneath a beer keg filled with water from a well.

It’s here that Piper and Dancier plan to write and illustrate children’s fables and a book about their experience with the cob house, a mix of frustration and inspiration that peaked this spring as the deadline to meet the county’s requirements loomed.

Piper and Dancier, with no hopes of expansion and no money to pay fines, went public with their story, sharing it in the local newspaper. Residents who had been standoffish began to rally around them.

“What’s going to hurt the environment more? A $3 million vacation home or a mud hut?” said neighbor Dezotell, who left corporate America in 1993 for an electricity- and plumbing-free cabin in nearby Loretta, Wis.

Finally, acceptance

Slowly, intrigued neighbors began stopping by this spring. Some donated a legal composting toilet. A log cabin builder visited and hatched a plan to build a cabin on their property in July for a class he teaches as long as the women help and donate some of their trees.

More than a year of contentiousness eased when the county agreed, allowing the cob house to remain as an accessory building.

Meanwhile, Piper and Dancier discovered a delicate balance between personal need and environmental stewardship. They learned to live off 10 gallons of water a day for bathing and cooking.

In their effort to be left alone in the woods, they ended up reconnected to society, through a small army of believers in their individualism who came to their aid when their dream was nearly lost.

“We have some really nice people in our lives,” Piper said.