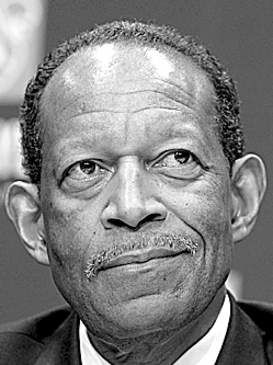

NFLPA union boss Upshaw dies at 63

Published 5:00 am Friday, August 22, 2008

- Gene Upshaw

NEW YORK — Gene Upshaw was a punishing blocker who intimidated opponents on the field. Off it, his power was greater.

A Hall of Fame guard for the Oakland Raiders, Upshaw died Wednesday at age 63 from pancreatic cancer, an illness he only learned about Sunday. His death cut short a 25-year, post-playing career as union boss in which he led NFL players to riches that would have been almost unimaginable when he was a rookie in 1967.

“The Raider organization, the National Football League, and the world have lost a great man,” Raiders founder and owner Al Davis said. “He is as prominent a sportsman as the world has known.”

The unexpected nature of Upshaw’s death shocked people throughout the NFL. This was a towering man who played 15 years — all for an Oakland team that reached the Super Bowl three times and won twice.

Upshaw died Wednesday night at his home near California’s Lake Tahoe, the NFL Players Association said Thursday. His wife Terri and sons Eugene Jr., Justin and Daniel were by his side. NFLPA president and Tennessee Titans center Kevin Mawae said Upshaw was diagnosed Sunday after he fell ill and his wife took him to the hospital.

“Gene was a great player. He was an All-Pro. He was a Hall of Famer. If you look at the history of the NFL you’re going to find out that he was one of the most influential people that the league has known. He did so much, not only for the players, but also for the owners, the teams, and the game of pro football,” John Madden, who coached Upshaw when Oakland won its first Super Bowl, said in a statement.

“This is deeper than head of the union passing away, and it’s deeper than an ex-player. This is missing someone that is and was like family. It’s a tough day for all of us.”

In the wake of his death, many of those who had made him the focal point for their complaints over pension and health benefits for retired players softened the rhetoric and spoke of their respect for Upshaw.

As a player, the seven-time Pro Bowler was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1987, the first time he was eligible.

That also was the year Upshaw led the second players’ strike in five years, a short walkout that led to the embarrassing spectacle of games with replacement players, or “scab football” as it was jokingly called at the time.

By 1989, while the union was pressing in court for a settlement, the league implemented a limited form of freedom, called Plan B. A new, seven-year contract was finally worked out in 1993, bringing in a new age of free agency and salary caps.

That will go down as Upshaw’s legacy because it brought prosperity to both union members and owners, leaving many of today’s players appreciating Upshaw as a labor leader without knowing much about his playing career. Brandon Moore, the New York Jets player representative was 2 years old when Upshaw retired and said simply: “From what I hear, he was a pretty good player.”

What Upshaw did for Moore, and his counterparts is make them money — the salary cap for this season is $116 million and the players are making close to 60 percent of the 32 teams’ total revenues, as specified in the 2006 labor agreement. The players will be paid $4.5 billion this year, according to owners.

That sum led the owners to opt out in May from the collective bargaining agreement, meaning that if no new deal is reached, there will be an uncapped year in 2010, the season before the contract is expected to expire.

Upshaw, who had often been criticized for his close relationship with Paul Tagliabue, the former commissioner, and Roger Goodell, the current one, had been talking tougher than usual about upcoming negotiations, vowing that if the cap was ever abolished, he would never accede to a new one.

Upshaw’s death raises a big question mark about negotiations although the union’s executive committee tried to answer it quickly by appointing the union’s most experienced official, Richard Berthelsen, as the interim executive director.

Berthelsen, the NFLPA’s chief counsel and Upshaw’s top aide, has been involved in labor negotiations for 37 years and is expected to steer the union through the negotiations and then make way for a younger man, probably an ex-player such as Trace Armstrong or Troy Vincent, two past presidents, or former Minnesota running back Robert Smith, who has expressed an interest in the job.

But those decisions are in the future. On Wednesday, people from both the sports and labor world rushed to pay tribute to Upshaw, one of the few African-Americans to lead a major union. That there were few indications that Upshaw was ill made his death even harder to take.

“He was and will remain a part of the fabric of our lives and of the Raider mystique and legacy,” Davis said. “We loved him and he loved us. We will miss him.”

Said Indianapolis Colts center and player representative Jeff Saturday: “Everybody can sit back, and obviously, some people might criticize some of the things he’s done, but overall, I don’t think you could have asked for a better leader.”

Upshaw, blunt to a fault, wasn’t universally loved, especially by the retired players — he once said “I represent the current players” when reminded about their complaints about health care and benefits.

When Joe DeLamielleure, also a Hall of Fame guard, criticized Upshaw, the former Raider replied: “I’d like to break his neck.” But DeLamielleure was among to the first to react to Upshaw’s death.

“The reality of life for all the guys who played in the NFL, including Gene, is that we have a short life span. It’s just the way it is,” he said. “I have sympathy for his family. I have sympathy for his wife and children.”

Upshaw’s friends also recognized the strike-back part of his nature.

“In both careers, if you hit him in the head, he could hit you back twice as hard, but he didn’t always do so,” Tagliabue said. “He was very tough but also a good listener. He never lost sight of the interests of the game and the big picture.”

Many others echoed those thoughts.

“Gene Upshaw did everything with great dignity, pride, and conviction,” Goodell said. “He was the rare individual who earned his place in the Pro Football Hall of Fame both for his accomplishments on the field and for his leadership of the players off the field. He fought hard for the players and always kept his focus on what was best for the game. His leadership played a crucial role in taking the NFL and its players to new heights.”

Detroit Lions president Matt Millen was a rookie in 1980 when veteran Upshaw took him under his wing and Oakland won its second Super Bowl. He remembered his friend this way.

“You can look at that body of work that he had when he played and he’s in the Hall of Fame,” he said. “You look at the body of work since he’s played and it’s Hall-of-Fame material, too.”