Dry River Canyon

Published 5:00 am Friday, September 5, 2008

- Dry River Canyon

The Dry River Canyon has mojo. Lots of it.

It’s just not easy to tell the genuine from the imitation. There’s American Indian rock art here; Indians camped in and frequented the High Desert canyon in ancient times. But there are also petroglyphs of more recent origin: triangles, circles and hearts etched in the volcanic boulders. One latter-day artist even etched a date, “1983,84,” into the stone.

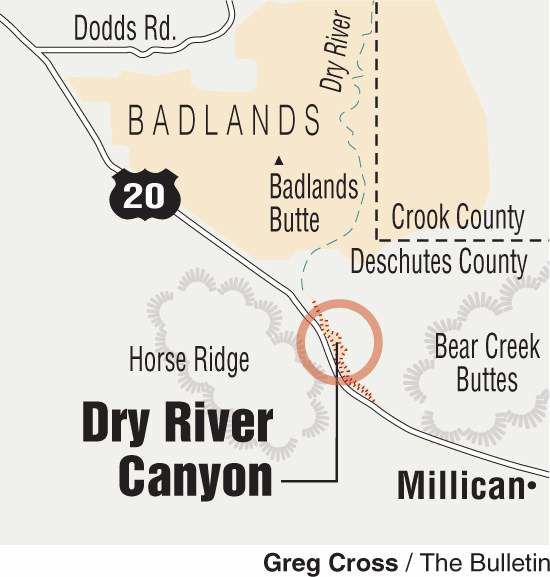

Despite all that, this juniper- and pine-studded slot that runs from Horse Ridge down into the Badlands Wilderness Study Area feels like the land that time forgot. U.S. Highway 20 runs just behind the rim to the south, but down inside the canyon, things are pretty much the way they’ve always been. Or at least since the Pleistocene Epoch (more than 11,550 years ago), when a big lake in the Millican area busted through a natural lava dam, sliced into the hillside and scoured the cleft with water and rock. The water’s gone, but a hiker gets the sense of what went before.

There are basalt boulders strewn hodgepodge the length of the canyon, and the rimrock and caves along the steep walls make the trek from the eastern edge of the Badlands up about 2½ miles to the end of the trail interesting all the way.

Not far into our hike, we heard the descending staccato call of a canyon wren, a good omen. That and the mule deer tracks along the narrow trail lent a wild Western ambience to the place. If plateaus and mesas are sand-blasted and lonesome, desert canyons are mysterious and cloistered; you never know what’s around the next bend. The uneven footing also keeps your head in the game; the odd-angled rocks make necessary hundreds of little decisions throughout the hike.

An informational sign at the Dry River Canyon viewpoint on U.S. Highway 20 at the head of the canyon confirms that the ancient river was once the scene of many Indian encampments near its source at the lake. In places like this, I’m constantly marveling at the intransigence of hills and rocks. Geologic time notwithstanding, how many pre-European natives traipsed this same path and saw these same sights. Did the bright yellow blooms of the rabbitbrush contrasted against the browns and grays of the rocks cause them to nod in appreciation? Did the slight chill in the September breeze quicken their step? Did the yowl of coyotes or the clear trill of a canyon wren speak to something deep inside that assured them that this was home? Of course.

All we have now are some abstract petroglyphs, but of course. How could they not? On the hike, you’ll see lava rocks burnished by the water that once flowed there. There are also tinajas, rocks with smooth holes in them that catch water from the scant rainfall in the area. This is a good hike in fall and early winter. When there’s snow to the west, the Badlands and Dry River Canyon are often clear. But take heed: The canyon is off limits each year from Feb. 1 through midsummer to give raptors a chance to nest undisturbed. Allow several hours for this hike. There’s plenty of shade for a picnic in the canyon, and you’ll want to look for petroglyphs and wildlife along the way out and back.

From Bend, drive east on U.S. Highway 20. Turn left on an unmarked paved road just past milepost 17 at the bottom of the grade. Turn right into the gravel pit and continue to a dirt road on the far right side of the pit area. Follow the road to the parking area and trailhead. Trail distance: Varies, up to five miles out and back. Trail Access: Hikers, dogs on leashes allowed. The top of the canyon abuts private property. Please respect property rights.

Contact: Bureau of Land Management, 541-416-6700.

— Jim Witty