Rollin” on the rivers

Published 5:00 am Sunday, September 7, 2008

- Rollin” on the rivers

HOOD RIVER —

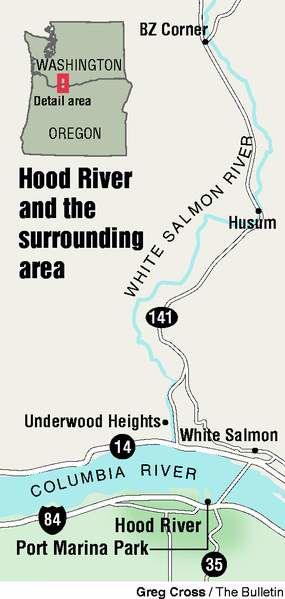

Husum Falls is nothing if not intimidating. One of the few Class Five rapids in the Pacific Northwest to be navigated by professional rafting companies, it spans the heart of the White Salmon River, which flows from Mount Adams into the Columbia River opposite the Oregon town of Hood River.

Class Five is the most challenging rapid that can be attempted. There are only six classes in the North American river rating system, and Class Six is considered impossible to navigate, like a 50-foot waterfall. Class Four is a major rapid, potentially perilous. Class Five is in itself life-threatening.

There’s a bridge on Washington State Highway 141 that crosses the White Salmon immediately above Husum Falls. Many drivers park their vehicles on either side of the bridge and walk up the road to peer over the rail at the watery chasm, a 10-foot drop framed by two large rocks that resemble a monster’s bicuspids.

When I booked a half-day rafting trip on the White Salmon with Zoller’s Outdoor Odysseys, I knew the route from BZ Corner to Northwestern Lake would carry us directly over Husum Falls. But I assumed the company would portage its riders around the giant rapid to assure their safety.

I was wrong.

Catching the wind

The charming town of Hood River, on the Columbia 143 miles north of Bend, is the hub of activity not only for rafting the White Salmon but for a plethora of other recreational opportunities.

When a friend and I began planning a weekend of water-driven sports — I wanted to go rafting, she was interested in trying windsurfing — Hood River was an obvious choice.

There’s a wind-tunnel effect on the Columbia River where it sweeps through its gorge 60 miles east of Portland. The stiff breezes made Hood River a perfect location for windsurfing when the sport took off in popularity in the early 1970s. (It had been invented around 1964.) Today, Hood River is the headquarters of the U.S. Windsurfing Association and is considered by many to be the windsurfing capital of the world.

But there’s a new kid on the block in Hood River as well. Kite boarding made its debut at the start of the 21st century, and now, on any given day, there are as many or more recreationists harnessing themselves to giant kites (and soaring on and over the river) as there are windsurfers.

The community of about 7,000 people has embraced each of these sports — windsurfing, kite boarding and river rafting — as well as kayaking, boating, fishing, bicycling, skiing, snowboarding and other activities. Cruise down Oak Street, downtown Hood River’s main drag, and you’ll pass the Kayak Shed, the Gorge Surf Shop, Airtime Kite, Doug’s Sports, the Gorge Fly Shop, 2nd Wind Sports Consignment and more.

Surrounding Hood River is the Columbia Gorge National Scenic Area, a paradise for hikers and bicyclists; and the Mount Hood Meadows ski area is a half hour’s drive south.

Hood River has more than sports, however. Its valley is dense with fruit trees — apples, peaches, pears and cherries — that blossom brightly in the spring and fill fruit stands in the fall. Several of Oregon’s finest wineries are located here as well. Hood River also has several intriguing museums, including the new Western Antique Aeroplane and Automobile Museum south of town.

Learning to windsurf

A light afternoon breeze blew up the Columbia when my friend and I arrived for her windsurfing lesson. She had made a reservation with Hood River WaterPlay, with headquarters at Port Marina Park on the river. Other companies offering lessons at lower rates were based out of trucks parked nearby, but WaterPlay was the only one we saw with a permanent structure.

The Hood River itself, flowing north off Mount Hood, merges with the Columbia on the west side of Port Marina Park, dividing it from the Port of Hood River Event Site and a large, sandy spit. This is the hub of the Columbia River boarding scene. We watched as kite boarders toted heavy packs through waist-deep water to get to the spit from a pebbly beach. A school-age windsurfer skimmed across the bay. But competition for water space appeared too keen for this to be an ideal place for a lesson.

WaterPlay had already considered that. My friend was outfitted in a wetsuit and then sent to a beginners’ area on the east side of the Best Western Hood River Inn, a half-mile upriver. A section of river was roped off about 100 feet offshore, keeping novices from errantly getting too far out away from the river bank until they are ready.

Instructor Sal Ledezma, 20, greeted my friend and her fellow student, Elizabeth Healy, of Tumwater, Wash. “You don’t see very many beginners in this sport anymore,” he said. “It feels like kite boarding is getting more popular. But I’m glad you’re here. I love to teach people.”

A five-year veteran of the sport, Ledezma began his course with 45 minutes of dry-land training. He began by explaining “beam reach,” where sailors achieve maximum velocity by keeping their sail at a 90-degree angle to the wind at their backs. The instructor employed a hand-painted board to describe the effect of different angles on the sail.

“The wind here almost always blows upriver,” he said, “but it changes by about 60 degrees as soon as you get a little ways offshore into the river.”

Ledezma schooled his students in keeping their feet along the center line of the board and squatting as they used the up-pull rope to raise the sail until they could grab the boom, or center bar. “Hurting your back is a big thing in this sport,” he warned. “The basic position is knees bent, hips out, butt in, back slightly arched.”

Moving to the water, the instructor put the neophytes on large boards with seven-foot sails, opposite of the short, skinny boards with 10- to 12-foot sails employed by experts.

He cautioned them to use their weight to shift the position of the sail. “Guys generally suck at this because they try to muscle it,” he said. “You don’t want to do that.”

But he added, “There’s only so much I can teach you guys. Then you’ve got to feel out the rest on your own.”

After an equal amount of time on the water to her dry-land training, my friend said she’d had enough; even wearing the wetsuit, she was cold. Healy kept at it and, despite a couple of chilly spills, appeared to be a river athlete in the making.

Big-water rafting

The next morning belonged to me. My river trip began at 9, so we paid the 75-cent toll to cross the Columbia on the Hood River bridge and shot up the White Salmon River road through Husum to the small community known as BZ Corner.

Zoller’s Outdoor Odysseys was founded by Phil Zoller 35 years ago, making it perhaps the oldest rafting business in the Pacific Northwest. Today Phil’s son, Mark, owns the business, and he has four children in their teens and 20s who may someday be in line to take it over.

The heart of the Zoller compound today is a two-story lodge where rafters may check in, buy souvenirs and look at photos when their trip is over. It’s surrounded by a series of huts where wetsuits, jackets, helmets and other equipment are kept, as well as changing rooms and a central staging area.

Twenty-six people were booked for the half-day trip at 9 a.m., and 20 of them were young soldiers from Fort Lewis, Wash., patiently awaiting a posting in the Middle East, perhaps Iraq. I spoke with several of them — one from Minnesota, another from Florida, a third from New Hampshire (“the greatest place in the world,” he said) — and none had ever been rafting before. They were equally divided among four different rafts.

I drew the non-military raft with two Texans, who had just completed a two-day run from Timberline Lodge to the coast, and three friends from the Portland area, all of them mothers home-schooling their children. The man steering our raft was 20-year-old Zack Zoller, third generation of the family of rafters.

We descended a steep, 100-step staircase to the river and launched our boats beside a rocky embankment. We descended through a series of rapids with names like Grasshopper, Corkscrew and Granny Snatcher; slid past a dangerous undercut cave; and dropped down aptly named Stairstep.

About 45 minutes into the voyage, we approached Husum Falls. Zoller twice offered to bring anyone to shore who feared the Class Five challenge, but every person in our boat was willing to tempt a watery grave. One soldier, a big-city boy, opted out and rejoined his raft after the falls; I couldn’t help but imagine the razzing he might later get from his comrades.

The approach was deceiving. Only by watching a couple of the boats ahead of us could we gauge where the rapids made their sudden drop. Zoller plunged us through the jaws, the point of no return, before we knew what hit us.

In only a split second he shouted “Down! On the floor!” and as we made our dives, our rubber raft was nearly vertical. In another moment we were completely immersed in foam, with only our blue helmets visible to the crowd of onlookers gathered on the bridge. Yet we bobbed back up and proceeded downriver as if nothing out of the ordinary had occurred.

After one additional small rapid, we emerged upon Northwestern Lake, which is really only a calm, wide spot on the river held back by Condit Dam. The PacifiCorps project is scheduled to be removed in the next couple of years, opening a new section of river to spawning salmon and avid rafters and kayakers.