Protein researchers take Nobel Prize in chemistry

Published 5:00 am Thursday, October 9, 2008

- Protein researchers take Nobel Prize in chemistry

One Japanese and two American scientists have won this year’s Nobel Prize in chemistry for taking the ability of some jellyfish to glow and transforming it into a ubiquitous tool of molecular biology for watching the dance of living cells and the proteins within them.

The fluorescent proteins are now routinely used for observing the growth and fate of specific cells like nerve cells damaged during Alzheimer’s disease.

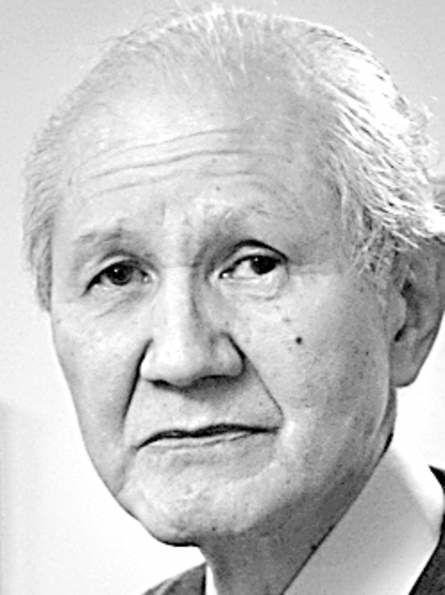

The winners are Osamu Shimomura, 80, an emeritus professor at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass., and Boston University Medical School; Martin Chalfie, 61, a professor of biological sciences at Columbia University; and Roger Tsien, 56, a professor of pharmacology at the University of California, San Diego.

Biologists have long observed that some sea creatures glow in the dark. In 1962, Shimomura, then a researcher at Princeton, and Frank Johnson, a Princeton biology professor, isolated a specific glowing protein in the Aequorea victoria, a jellyfish that drifts in the ocean currents off the west coast of North America.

The protein looked greenish under sunlight, yellowish under a light bulb and fluorescent green under ultraviolet light. Shimomura and Johnson called it the green protein, but now it is known as green fluorescent protein, or GFP for short.

The green fluorescent protein consists of a chain of 238 amino acids bent into a beer can-like cylindrical shape, and for two and a half decades it remained a little-known biological curiosity.

Chalfie first heard about the protein in 1988, and thought he might be able to use it in his studies of Caenorhabditis elegans, a transparent roundworm. He thought that the fluorescent protein could be made to serve as a biological marker by splicing the gene that makes the protein into an organism’s DNA next to a gene switch or another gene.

“That serves as a lantern,” Chalfie said, and biologists would be able to see when specific genes turn on or off and where different proteins are produced.

He was not able to pursue the idea until Douglas Prasher, a scientist then at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, found the GFP gene and shared it with Chalfie in 1992. Chalfie said that within a month his group was able to insert the gene into E. coli bacteria.

In 1994, Chalfie and his collaborators reported that they had inserted the protein into six cells of the C. elegans worm. When placed under ultraviolet light, those cells shined green, revealing their location.

Tsien was thinking along similar lines as Chalfie, also contacting Prasher. But for the biology experiment he wanted to conduct, he needed two colors of fluorescent proteins. Tsien started mutating the GFP gene and looking at the resulting proteins. Some, he found, glowed blue instead of green.

“That was the first evidence you could change the color,” Tsien said.