Militants turn to small bombs in Iraq attacks

Published 4:00 am Friday, November 14, 2008

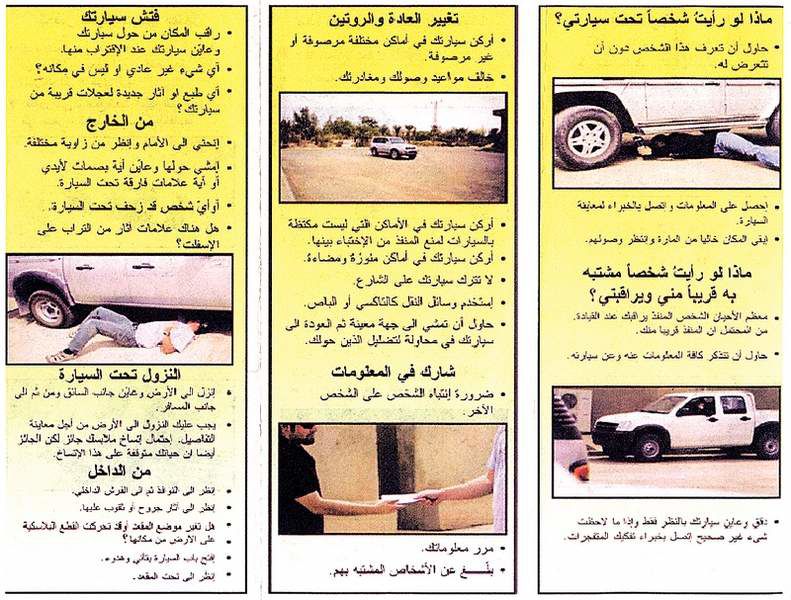

- A pamphlet handed out to the public by Iraqi authorities gives information on sticky bombs — explosive devices that are becoming popular with insurgent groups. Light and portable, the bombs are about the size of a fist and attach to a magnet or adhesive strip.

BAGHDAD — They are usually no bigger than a man’s fist and attached to a magnet or a strip of gummy adhesive — thus the name “obwah lasica” in Arabic, or “sticky bomb.”

Light, portable and easy to lay, sticky bombs are tucked quickly under the bumper of a car or into a chink in a blast wall. Since they are detonated remotely, they rarely harm the person who lays them. And as security in Baghdad has improved, the small and furtive bomb — though less lethal than entire cars or even thick suicide belts packed with explosives — is fast becoming the device of choice for a range of insurgent groups.

They are also contributing, in the midst of an uptick in violence, to a growing feeling of unease in the capital.

“You take a bit of C4 or some other type of compound,” said Lt. Col. Steven Stover, a spokesman for the U.S. military in Baghdad. “You can go into a hardware store, take the explosive and combine it with an accelerant, put some glass or marble or bits of metal in front of it and you’ve basically got a homemade Claymore,” a common anti-personnel mine.

Sticky bombs are not an Iraqi innovation. “Limpet mines” were attached to the sides of ships during World War II, and magnetic booby traps were used during the conflict in Northern Ireland. Magnetic IEDs, or improvised explosive devices, homemade bombs, were first used in Iraq in late 2004 or early in 2005, according to the American military.

But sticky bombs have become steadily more common since the start of this year, from an average of two explosions a week caused by them this spring, to about five per week more recently, Stover said.

Factory production

According to figures compiled by Iraq’s Interior Ministry, sticky bombs killed three people and wounded 18 in Baghdad alone during the month of July. In October, nine people were killed and 46 more were injured by sticky bombs.

Casualty rates caused by sticky bombs are still relatively low. But recent raids on insurgent groups have uncovered caches of the bombs, even “sticky bomb factories,” Stover said. And magnetic IEDs have recently been made an explicit part of the training that American soldiers posted to Baghdad receive on arrival.

“We make our soldiers aware of the latest threat, and the latest IED threat is these magnetic IEDs,” he said. “We put them in their hands and say, ‘Hey, soldier, this is what this thing looks like.’ They’re sometimes used against us — our vehicles are metallic, too.”

Iraqi and U.S. officials acknowledge that “sticky bombs” have been an effective means of spreading terror among Iraqi urban populations but note that, paradoxically, the bombs are also a sign that terrorists are finding it harder to move freely.

“The safety barriers, the walls themselves, have largely taken away these catastrophic attacks that you saw in the past,” Stover said. “The smaller bombs are not capable of causing that catastrophic attack. But they’re causing a lot of panic.”

Gen. Jihad al-Jabieri, an explosives expert at the Iraqi Interior Ministry, said that “sticky bombs emerged at the beginning of this year after a clear drop in attacks caused by car bombs, IEDs and explosive vests.”

“Military operations reduced the availability of the explosive materials that were used in car bombs,” Jabieri said.

Sticky bombs have frequently been used to attack Iraqi government and military officials, and important businessmen. In July, Faris Amir, the deputy general director of Baghdad’s traffic police, was wounded by a sticky bomb attack. In September, an executive at the Al Arabiya satellite channel narrowly survived an assassination attempt by sticky bomb, which destroyed his car. In October, the lawyer Waleed al-Azzawi and the police commander of Diwaniya province, Omar Abu Atra, were killed in Baghdad by sticky bomb attacks on their cars.

The media department of Iraq’s Interior Ministry has begun a pamphlet distribution campaign to educate the public about the threat of sticky bombs.

Baghdad residents say they are learning to examine the underbellies of their cars, and to take quick peeks under their tables in restaurants.

Mohammed Sadoon, a 28-year-old cashier in the coffee shop that his family owns, said that he had been keeping an especially sharp eye on his customers lately.

“I noticed that there have been lots of sticky bombs recently, so we watch everyone who enters our shop, and we make sure to check the bathrooms and under tables,” Sadoon said. “My brother always checks underneath our car and looks at any bags that are left inside our shop because we’ve heard from the policemen and soldiers that they always check suspected cars for this small, rapid and high-explosive bomb.

“Let me be frank — if we catch anyone trying to set a sticky bomb in our place, we will beat him very severely before we inform the authorities,” he added.

Interior minister urges action on security pact

BAGHDAD — Iraq’s interior minister has criticized the country’s politicians for not approving an agreement that would allow U.S. troops to operate in Iraq after the end of the year and called their continued presence crucial.

“The security agreement is important for Iraq to ban, and stop foreign influence and interference,” minister Jawad al-Bolani said in an interview Wednesday. “The Iraqi people need this security agreement.”

Bolani, one of the few top Shiite leaders to speak publicly in favor of the agreement, said Iraqi politicians should declare their stances on the agreement.

“They should be outspoken,” he said. “You have to have a clear vision” that can be articulated.

Top Iraqi leaders, including Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, have largely kept their views private during protracted and contentious negotiations on the status of forces agreement, which would replace the United Nations Security Council mandate when it expires at the end of the year.

— The Washington Post