Coosje van Bruggen helped create memorable sculptures

Published 4:00 am Wednesday, January 14, 2009

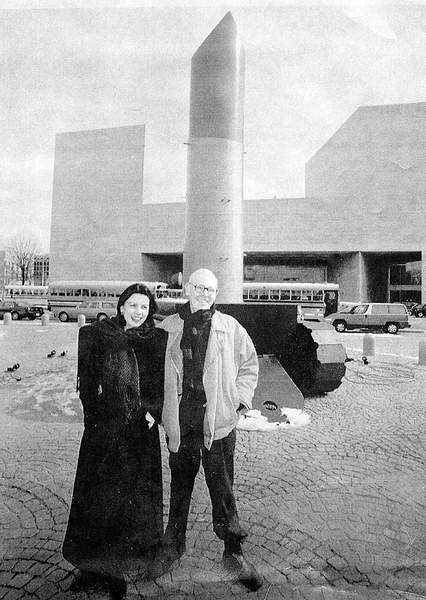

- Artist Claes Oldenburg and his wife, Coosje van Bruggen, stand in front of his giant lipstick sculpture on Feb. 9, 1995, outside the National Gallery of Art in Washington. Van Bruggen, 66, a critic, art historian and sculptor who collaborated with her husband on his giant sculptures of mundane objects, died Saturday in Los Angeles.

LOS ANGELES — Coosje van Bruggen — an art historian, writer and curator whose partnership with her husband, artist Claes Oldenburg, turned ordinary objects into startling monuments — died Saturday at her residence in Los Angeles.

She was 66. The cause of death was metastatic breast cancer.

Trending

Van Bruggen was the author of scholarly essays on the work of major contemporary artists, including John Baldessari, Bruce Nauman and Gerhard Richter. She also wrote a monograph on architect Frank O. Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain.

Giant bowling pins

But she is best known for collaborations with Oldenburg, which have placed giant trowels, shuttlecocks, bowling pins and typewriter erasers on parkland, civic squares and museum grounds in Europe, Asia and the United States. Cologne, Germany, has its upside-down ice cream cone; San Francisco, its bow and arrow; Denver, its dustpan and broom.

In Los Angeles, “Collar and Bow” — a 65-foot metal and fiberglass sculpture in the shape of a man’s dress-shirt collar and bow tie, designed for Walt Disney Concert Hall — was stalled and eventually canceled because of technical problems and escalating costs. But van Bruggen and Oldenburg are represented in the city by other public works, including “Toppling Ladder With Spilling Paint” at Loyola Law School in downtown Los Angeles and “Binoculars,” the central component of a building in Venice designed by Gehry.

Born and educated in Groningen, Netherlands, van Bruggen got her professional start as a curator at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Enschede.

‘Unity of opposites’

Trending

Her first encounter with Oldenburg came in 1976, when she helped him install his 41-foot “Trowel I” on the grounds of the Kroller-Muller Museum in Otterlo.

The Swedish-born American sculptor and draftsman — who emerged in New York with the Pop movement and became known for his light touch — and his scholarly Dutch associate might have appeared to be an unlikely match. But their relationship grew into what Oldenburg called “a unity of opposites” and they were married in 1977.

Van Bruggen, who became an American citizen in 1993, continued to work independently throughout her career. She helped to select artists for Documenta 7, the 1982 edition of an international contemporary art exhibition; contributed articles to Artforum magazine from 1983 to 1988; and served as senior critic in the sculpture department at Yale University School of Art in 1996-97.

As the years passed, she also played an increasingly prominent role in the “Large-Scale Projects” that the couple produced as a team.

Paul Schimmel, chief curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art, who met van Bruggen in the 1970s, said that he was immediately impressed by her seriousness.

“She was among the art historians most respected by artists,” he said Monday. “Thorough and rigorous, she left no stone unturned. She questioned everything. She was admired and, in some ways, feared a little because she didn’t accept any assumption. She was known for her almost scientific approach to looking at an artist’s oeuvre.”

The collaborative work of van Bruggen and Oldenburg has been the subject of about 40 exhibitions, including large surveys at MOCA, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, Museum Ludwig in Cologne and the Hayward and Serpentine galleries in London.