Controversy surrounds public health insurance

Published 5:00 am Thursday, April 9, 2009

- Controversy surrounds public health insurance

One of the most controversial proposals in both state and national health reform efforts is the idea of a public insurance plan.

The idea is that a plan run by the government would offer health insurance, competing alongside private health insurers’ plans. Individuals or small businesses that currently buy private insurance would be the most likely to purchase the public coverage.

For advocates, a public plan is essential for reducing health care costs and bringing transparency to the insurance system. For those opposed, a public plan risks destroying the private insurance market and creating a system of complete government-run health care.

“The debate about the public plan has been polarized,” said Bill Kramer, a health care consultant in Portland who has helped advise the Oregon Health Fund Board. “Both the hopes and fears are exaggerated.”

In Oregon, the public plan was proposed by the Health Fund Board as a possibility to go along with other reforms in the insurance market, though it is not included in the first phase of the reform.

At the federal level, President Barack Obama included a public plan in his health care proposal while on the campaign trail and has offered cautious support as president.

“The thinking on the public option has been that it gives consumers more choices,” the president said at a recent health care forum. “And it helps … keep the private sector honest because there’s some competition out there.”

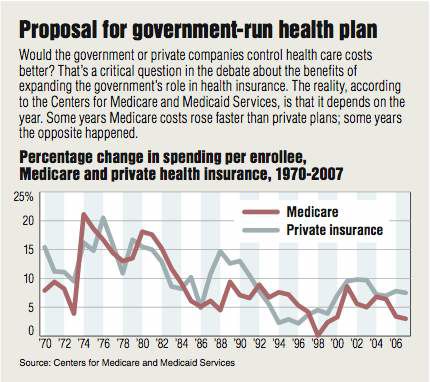

At issue is how large a role the government should play in health care and how big the public plan would get. Private insurers fear that the public plan could push them out of business.

One of the main issues, they say, is that it’s likely that the public plan would determine provider reimbursement the same way that it is determined in the current government health plans, Medicare and Medicaid.

Unlike private health insurers, who haggle with providers routinely over what they will be paid, the government names its price. Hospitals and doctors can choose to accept that price or opt out of the system.

In a public plan, if it were run the same way, the premiums could be lower than in private plans because reimbursements would be lower. That could lead consumers to flock to the public plan, but some say at their peril.

“If government were able to set the prices it paid to doctors and hospitals, it would drive many insurers out of the market,” said Kramer. “If the end game is a single-payer (health care system), that’s hard to predict, but it would put us on the path toward that.”

A single-payer health system, as exists in Canada, is an anathema to many who tout the virtues of market competition in health care. “What you should be concerned about as a consumer is the competition and a competitive marketplace,” said Mike Becker, director of legislative and regulatory affairs for Regence BlueCross BlueShield of Oregon. “If you create an option that initially seems to be a low-cost option but it eliminates many insurers, over time you will have less choice and more cost.”

Others dismiss the notion that the public plan would displace private insurance. “Free market advocates contend that the public plan would somehow be able to set pricing and dominate markets and therefore it’s a smoke-and-mirrors way to get to a single-payer system,” said Joseph Paduda, a health care consultant based in Connecticut. “That’s patently ridiculous.”

Paduda said that doctors and hospitals would have the ability to reject the public plan, deciding if the reimbursement were too low they wouldn’t take the insurance. While that might be difficult — if not impossible for some providers, particularly hospitals and particularly if the reimbursement is tied to Medicare reimbursement — providers would almost certainly not be required to opt in.

For those who wanted to buy the public plan in Central Oregon, there could be problems, said independent insurance broker Robb Hayden. Here, he said, it’s already difficult to find a doctor willing to take Medicare. Those who go looking for a doctor who will take Medicare, said Hayden, find “there are darn few of them in Central Oregon.”

Besides a provider’s ability to reject the terms of the public plan, Paduda said there are already large insurer monopolies in many areas that could make it difficult for any new plan, even one with government backing, to come in. “I’ve worked for health plans,” he said. “I can tell you, they don’t give up (their) share easily.”

Those monopolies, many say, can be detrimental to consumers, particularly when they give insurers little incentive to lower costs. For some, a public plan that could bring extra competition could shake up the markets in those areas, perhaps bringing needed changes.

In Oregon, however, insurers have a looser hold on the market than in many places, said Becker. He called the state’s “the most competitive health insurance market in the country” noting that eight state-based insurers compete for market share. He worries that some may disappear if forced to compete with a public plan. “When you look at these solutions that are ostensibly to promote competition, you will actually lessen competition here in Oregon.”

To date, there are few specifics on how a public plan would be structured at either the federal or the state level. Details, such as how the plan would determine medical reimbursements, fix premiums and market itself consumers, remain up in the air.

Still, with national attention turned to health reform, it’s an issue that is unlikely to fade anytime soon. Whether it will come to pass, however, with positions staked on both sides, is another matter.