Tucson hits on a solution to water lack: Harvest the rain

Published 5:00 am Monday, July 6, 2009

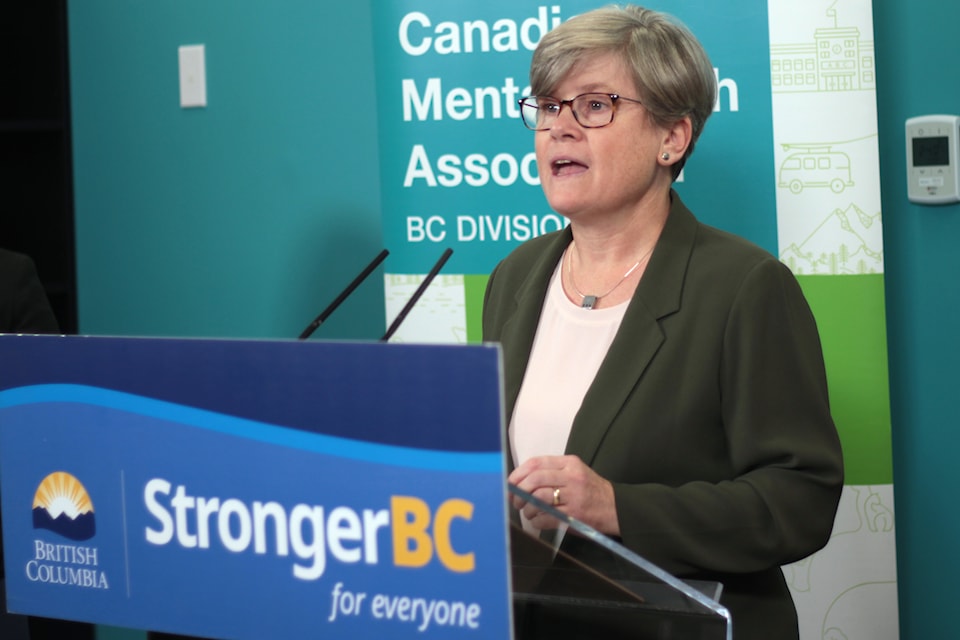

- Eric Barrett is the landscape architect for a remodeling project at Target in Tucson, Ariz. The parking lot will feature native trees planted in depressed areas to retain more water. Now the site will “hold 15,000 cubic feet of water, which equates to roughly 112,200 gallons per rainstorm,” Barrett says.

TUCSON, Ariz. — Long dependent on well water and supplies sent hundreds of miles by canal from the Colorado River, this desert city will soon harvest some of its 12 inches of annual rainfall to help bolster its water resources.

Under the nation’s first municipal rainwater harvesting ordinance for commercial projects, Tucson developers building new business, corporate or commercial structures will have to supply half of the water needed for landscaping from harvested rainwater starting next year.

Already, the idea has become so popular that at least a half dozen other Arizona communities are looking to emulate Tucson’s approach.

“What we learned frankly is that we’re wasting a lot of water. It’s been our tradition here to shove it into the streets and get rid of it as soon as possible,” said David Pittman, southern Arizona director of the Arizona Builders’ Alliance.

Rainwater harvesting is also catching on nationwide, with Georgia, Colorado and other states legislating to allow or expand use of various types.

From Portland and Seattle to San Francisco and Austin, Texas, voluntary rainwater harvesting is irrigating plants or being used in other ways instead of merely falling onto roofs, parking lots or pavement and being drained into sewers as wastewater.

“There’s only so much water. Unfortunately, Americans are terribly, terribly wasteful with water, and we’re running out,” said Tim Pope, who builds harvesting systems in the San Juan Islands near Seattle and heads the American Rainwater Catchment Systems Association.

Water supplies from the Colorado River are likely to diminish from effects of global warming and increasing demands from other states in the West. And groundwater is carefully managed to prevent overpumping the water that supplies the 1 million people who live in growing metropolitan Tucson.

That makes conservation and rainwater harvesting all the more important.

Largely rural Santa Fe County in New Mexico has required harvesting using cisterns or similar water-collection structures, pumps and drip irrigation for commercial and residential development since last year.

It had allowed passive harvesting, by which runoff is channeled into soil from rooftops, parking lots and similar sites.

That’s the approach Tucson’s commercial ordinance takes, though active harvesting is allowed, too.

Landscaping needs account for about 40 percent of water use in commercial development and for about 45 percent of household water consumption, “so there is huge potential,” said Tucson City Council member Rodney Glassman, who spearheaded efforts to achieve the ordinance.

Rainwater harvesting holds particular appeal in the desert because of the combination of drought conditions and limited sources.

Glassman, a first-term councilman, campaigned in 2007 for rainwater harvesting in new commercial development, and systems that capture water from washing and bathing in new homes.

Last year, Tucson’s water utility delivered more than 131,000 acre-feet of water, including 26,000 acre-feet of reclaimed wastewater. According to Glassman, experts estimate more than 185,000 acre-feet of rainfall is available per year.

An acre-foot is about 326,000 gallons, enough to cover an acre a foot deep or supply about two households for a year.

‘Giant disconnect’

Glassman, who holds a doctorate in arid land resource sciences, said he noticed “a giant disconnect between the need and desire for water conservation and public policy at the local level.”

Passing the rainwater harvesting ordinance “makes conservation the rule rather than the exception,” he said.

In addition to adopting the harvesting ordinance, Tucson’s City Council also approved another measure requiring a plumbing hookup in new homes so that wastewater from washing machines, sinks and showers may be sent to separate drain lines, if homeowners want, at an additional expense. Those lines can be connected to irrigation systems.

Glassman brought developers, architects, environmentalists and ecology advocates together, who eventually proposed a law calling for 50 percent of landscaping needs for new commercial projects to come from rainwater.

“We ended up with a compromise, a practical solution that results in 50 percent less water that has to be diverted from our city water system that has to go on desert plants,” Tucson developer George Larsen said. “Nobody thinks it’s perfect, but everybody winds up thinking it works.”

A remodeling project at a Target big-box store on Tucson’s northwest side reflects the kind of changes the rainwater harvesting ordinance will bring.

Its parking lot and garden borders are being re-landscaped and incorporate some of the ordinance’s elements, even though it isn’t yet required. The plan features 300 mostly native trees, such as palo verdes and sweet acacias, planted in depressed areas amid the 620 parking spaces. Shrubs also will be grown along the site’s border areas.

Rainfall will run off from the asphalt into the soil strips, sloped lower than the parking bays.

“The more that you can depress areas, the more water that you’re going to retain,” said Eric Barrett, the project’s landscape architect. He said the site previously had only about four native trees, some palm trees and one bank of oleanders, with no water retention.

“Now it’ll hold 15,000 cubic feet of water, which equates to roughly 112,200 gallons per rain- storm.”

States dig deep to monitor water

KINGSTON, N.H. — About a quarter mile into dense woods, geologists watch as a drilling rig twists a shaft deep into the granite bedrock of southeastern New Hampshire. They are searching for water — not to drink — but to watch.

State and federal agencies have been watching, or monitoring, lakes and rivers for more than a century, but less attention has gone to vast amounts of water in cracks and rock fissures deep underground, leaving a void in understanding a resource growing in importance as demands for water increase, and surface water sources are being used to the fullest in many areas.

New Hampshire is drilling a series of wells to monitor groundwater in cracks in granite hundreds of feet below the surface. The goal is to allow scientists to check for contamination; learn about how long it takes for rainfall or melting snow to make its way into the supply; and keep tabs on how climate change, population growth and development affect the water.

Groundwater provides drinking water for 130 million Americans and 42 percent of the nation’s irrigation water, and while many states have monitored groundwater, they have done so for state-specific reasons, using different criteria. So, while groundwater supplies spread beneath large regions, monitoring generally stops at state lines.

“Some states have several hundred wells and sample them four times a year. Others have absolutely nothing,” said New Hampshire’s state geologist David Wunsch.

The goal of forming a network got a boost this year as Congress approved the SECURE Water Act, directing the U.S. Geologic Survey to work with states to develop a national monitoring program for underground water supplies, known as aquifers.

— The Associated Press