Lesson plan, too, is green at Bend’s new school

Published 5:00 am Thursday, September 24, 2009

- Lesson plan, too, is green at Bend's new school

Everything about Miller Elementary resembles other Bend-La Pine schools, but look closely and you’ll spot small differences that make this west Bend school more environmentally friendly.

On Wednesday, for example, students ate lunch just like students in other schools; but when they finished, they handed their used silverware and plastic plates to fourth- and fifth-grade students who washed them in the kitchen, rather than throwing away disposable bowls and utensils.

It’s one of the small ways the school’s administrators, teachers and students are trying to be more green, and the school could receive official recognition if it receives a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design certification.

The new school’s design has had its hiccups, including issues with the ventilation system and the parking lot. But administrators believe Miller Elementary’s green attributes could be copied at other area schools.

“The bottom line is, this will be a good school,” said Principal Steve Hill. “The LEED certification is just the frosting on the cake. … And if we have some success here, they may replicate this stuff at other schools.”

Part of the curriculum

To create LEED-certified building, the district took its elementary school prototype, then reworked the 67,000-square-foot facility to include things like solar panels on the roof, low-flush toilets and native plants in the landscaping.

LEED-certified buildings receive plaques as well as tax credits and cash incentives, and the certification shows that a building has met energy conservation measures and green-building standards.

Miller’s LEED certification is still pending. District officials are finishing final paperwork and engineers are inspecting the building to ensure everything is working properly. Miller Elementary would be the first district building to be LEED-certified.

The district expects to receive a gold certification. The highest certification is platinum.

At the entrance to the school, a touch-screen kiosk shows visitors the building’s LEED features. The screen also shows how the solar panels are working and how much power they’re generating.

That’s required for LEED certification, but it also will serve as an educational tool. Fifth-graders will research solar energy and likely chart the school’s energy production.

In fact, teachers will include environmental science in every grade level, with third-graders using food waste from the cafeteria to learn about composting and fourth-graders designing outdoor classrooms.

Students have gotten in on the act in other ways as well.

School officials decided to use washable plastic dishes and silverware instead of paper plates and plastic utensils, and fourth- and fifth-grade students are signing up to wash the dishes. They get a free lunch out of the deal, but mostly, they just seem to like it.

Only one other Bend-La Pine school, Westside Village, employs reusable dishes and silverware. The results at Miller Elementary have so far been impressive.

“I think our waste is about one-third of a typical school’s,” Hill said. “We fill about two trash cans at lunch. Some schools use 10 to 15.”

The school also is reducing paper waste in the classroom.

Like many other schools, Miller Elementary is offering its newsletter by e-mail, and only 12 families have asked to receive a paper edition. And in each classroom, the school has SMART boards, which are white boards that can be used with a computer. Hill expects SMART boards will reduce the handouts used in class, as students will be able to do the work on the SMART board instead.

Challenges

While the green movement at Miller Elementary is going well, there are challenges.

Some parents have complained about the design of the parking lot, Hill said. The lot, to meet LEED requirements, has 35 to 40 fewer parking spaces than High Lakes Elementary a mile away. In the mornings and afternoons, long lines of cars idle while parents wait to pick up children. That’s admittedly not very environmentally friendly.

About 210 students are riding the bus to school each day, and a few are riding bikes or walking. Hill noted the school is a bit out of the way for people interested in using alternative transportation.

“It’s hard to legislate what people do,” Hill said. “The design of the parking lot is to be pedestrian-safe, but it does move pretty slow.”

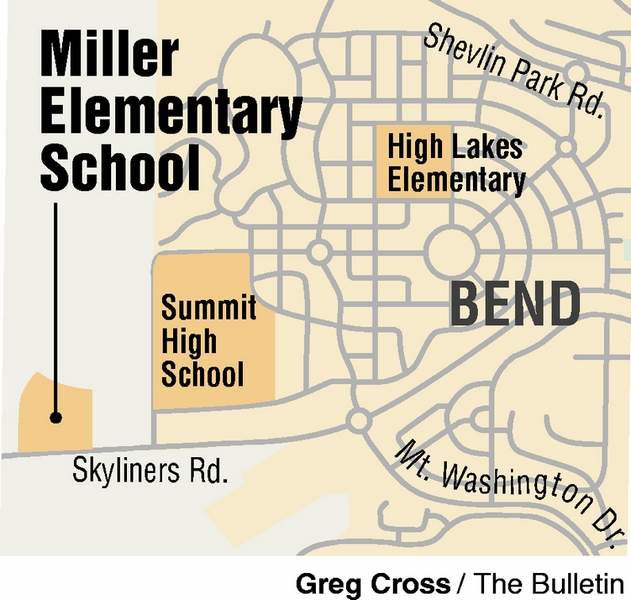

And the school’s location doesn’t help. Located off Skyliners Road southwest of Summit High School on the western edge of town, the school sits alone, with no homes around it.

“Our location is pretty rural right now,” Hill said. “Walking takes awhile. Some people ride their bikes, but when the weather changes that will change, too.”

Hill and Deputy Superintendent John Rexford would like more families to use school buses.

“We always try to encourage (buses),” Rexford said. “Obviously, one of the ways to ease the congestion will be getting more kids on buses or walking or biking. They’re probably busing about 40 or 45 percent of their students, and a typical elementary has 60 or 65 or even 70 percent of their students taking the bus. Those would be the goals.”

But Rexford said because some students come from rural areas to the north of the school, those bus routes may be longer and discourage families from using the bus. In the future, he believes more students will live closer to the school.

“It’s located well in the long run, but it’s not located well for walkers and bikers right now,” he said. “As development occurs and ends up wrapping around the school site, the reality is ultimately its attendance area will shrink and more students will live closer to the school. In the long run, it will probably take care of itself.”

Still in testing mode

School officials also are waiting to see how well other aspects of the school perform.

The school is testing a new type of flooring, Marmoleum. The thick linoleum is made from natural ingredients, but it’s also softer than tile, and Hill is interested to see how well it holds up over the school year.

The school installed low-flush toilets and waterless urinals. So far, those are working.

Right now, Rexford said, it’s too early to know whether the adaptations are worth the extra work.

“We’d like to see how the building operates through a whole year,” Rexford said. “Obviously, there are some new things there.”

One area that engineers are still working on is the ventilation system, which is designed to have windows open automatically when the building heats up. Sometimes they open and sometimes they don’t, so engineers are working with the software to make sure it works properly, Hill said.

At least in the case of Miller Elementary, Rexford said building a LEED-certified school was not particularly expensive. The district received about $500,000 in grants from the Oregon Department of Energy, the Energy Trust of Oregon and other groups.

“There’s a little bit of paperwork and administrative costs associated with LEED, but ironically, and we think primarily due to the bid market,” the per-square-foot costs to build Miller Elementary and the other new school across town, Ponderosa Elementary, were almost the same. “With the construction itself, we didn’t see anything (too expensive),” he said. “But I’d be the first to acknowledge the construction industry was declining at the time, so it may not be the best indicator.”

LEED certification also costs money. Registering a building for consideration costs between $450 and $600, and the certification process costs, on average, $2,000, according to the U.S. Green Building Council. The grants were more than enough to offset those fees and other expenses that came with the LEED certification.

“I think it’s a process worth going through at least once,” Rexford said. “I think when we have some time on this decision and we can see how the school operates, we’ll be able to reflect on how well the building’s working and we may choose to incorporate some of these features into future buildings and not seek LEED. We want to make that informed decision.”