Paul Samuelson won Nobel Prize in economics

Published 4:00 am Monday, December 14, 2009

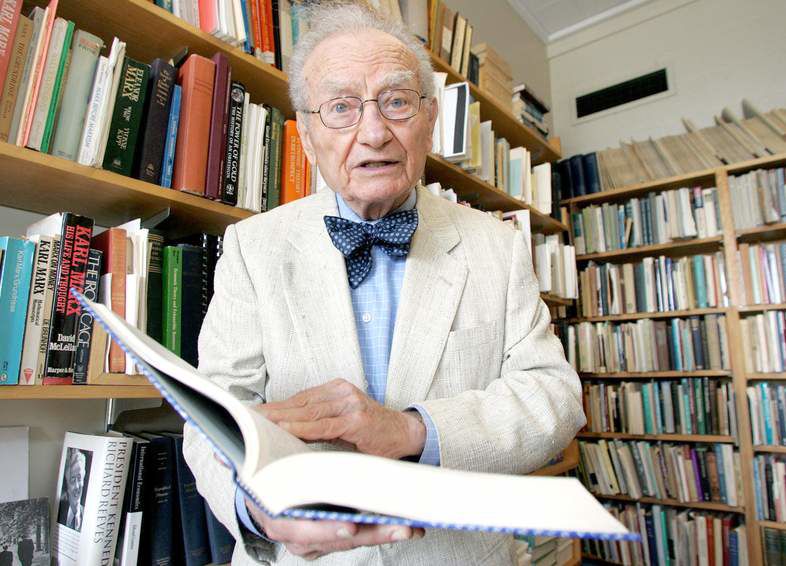

- Paul Samuelson, shown in his office at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Mass., on Sept. 3, 2004, was the first American Nobel laureate in economics.

Paul Samuelson, the first American Nobel laureate in economics and the foremost academic economist of the 20th century, died Sunday at his home in Belmont, Mass. He was 94.

His death was announced by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which Samuelson helped build into one of the world’s great centers of graduate education in economics.

A transformative figure

In receiving the Nobel Prize in 1970, Samuelson was credited with transforming his discipline from one that ruminates about economic issues to one that solves problems, answering questions about cause and effect with mathematical rigor and clarity.

When economists “sit down with a piece of paper to calculate or analyze something, you would have to say that no one was more important in providing the tools they use and the ideas that they employ than Paul Samuelson,” said Robert Solow, a fellow Nobel laureate and colleague of Samuelson’s at MIT.

Samuelson attracted a brilliant roster of economists to teach or study at the university, among them Solow as well as others who would go on to become Nobel laureates, like George Akerlof, Robert Engle, Lawrence Klein, Paul Krugman, Franco Modigliani, Robert Merton and Joseph Stiglitz.

Textbook became ubiquitous

Samuelson wrote one of the most widely used college textbooks in the history of American education. The book, “Economics,” first published in 1948, was the nation’s best-selling textbook for nearly 30 years. Translated into 20 languages, it was selling 50,000 copies a year a half century after it first appeared.

“I don’t care who writes a nation’s laws — or crafts its advanced treatises — if I can write its economics textbooks,” Samuelson said.

His textbook taught college students how to think about economics. His technical work — especially his discipline-shattering Ph.D. thesis, immodestly titled “The Foundations of Economic Analysis” — taught professional economists how to ply their trade. Between the two books, Samuelson redefined modern economics.

The textbook introduced generations of students to the revolutionary ideas of John Maynard Keynes, the British economist who in the 1930s developed the theory that modern market economies could become trapped in depression and would then need a strong push from government spending or tax cuts, in addition to lenient monetary policy, to restore them.

Samuelson explained Keynesian economics to American presidents, world leaders, members of Congress and the Federal Reserve Board, not to mention other economists. He was a consultant to the U.S. Treasury, the Bureau of the Budget and the President’s Council of Economic Advisers.

His most influential student was John F. Kennedy, whose first 40-minute class with Samuelson, after the 1960 election, was conducted on a rock by the beach at the family compound at Hyannis Port, Mass. Many of Samuelson’s lessons would have a bearing on decisions made during the Kennedy administration.

Versatile and funny

Remarkably versatile, Samuelson reshaped academic thinking about nearly every economic subject, from what Marx could have meant by a labor theory of value to whether stock prices fluctuate randomly. Mathematics had already been employed by social scientists, but Samuelson brought the discipline into the mainstream of economic thinking.

In the classroom, he was a lively, funny, articulate teacher. On theories that he and others had developed to show links between the performance of the stock market and the general economy, he famously said: “It is indeed true that the stock market can forecast the business cycle. The stock market has called nine of the last five recessions.”