Historic black schools restored as landmarks

Published 4:00 am Thursday, January 21, 2010

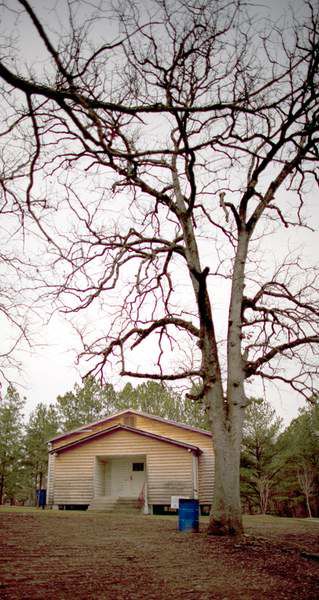

- The Rosenwald school as it looks today in Columbia, S.C.

COLUMBIA, S.C. — Until 1923, the only school in the largely black farm settlement of Pine Grove was the one hand-built by parents, a drafty wooden structure in the churchyard. Anyone who could read and write could serve as teacher. With no desks and paper scarce, teachers used painted wood for a blackboard, and an open fireplace provided flashes of warmth to the lucky students who sat close.

This changed after a Chicago philanthropist named Julius Rosenwald, the president of Sears, Roebuck and Co., took up the cause of long-neglected education for blacks at the urging of Booker T. Washington, the proponent of black self-help. By the late 1920s, 1 in 3 rural black pupils in 15 states were attending a new school built with seed money, architectural advice and supplies from the Rosenwald Fund.

“It was a big step up, going to a school that was painted and had a potbellied stove,” said Rubie Schumpert, 92, one of nine siblings who attended the Rosenwald school in Pine Grove — and one of three sisters who went on to college and careers as teachers.

If the desks and textbooks were hand-me-downs from white schools, at least there were real blackboards and rough paper for writing. If there was still no electricity, columns of windows maximized the natural light.

Today, this hard-used wooden building, which narrowly escaped demolition, is one of several dozen Rosenwald schools being restored as landmarks — newly appreciated relics of important chapters in philanthropy and black education. The schools were a turning point, sparking improved, if still unequal, education for much of the South, historians say.

The Smithsonian Institution’s new National Museum of African-American History and Culture is acquiring desks and other artifacts, as well as oral histories, from another Rosenwald school in South Carolina, said Jacquelyn Serwer, chief curator.

Pine Grove’s school was one of more than 5,000 built for rural blacks throughout the South between 1912 and 1937 with aid from Rosenwald. Spot surveys indicate that no more than 800 remain, their historical importance often unknown to residents and even to many of the dwindling alumni, according to the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which calls the schools an endangered treasure.

The need for them reflected the segregation of the age and the paltry financing of black schools. But historians say their blossoming also demonstrated the strong community ties forged by rural blacks and a fierce determination to educate their children despite official indifference.

“We were on the verge of losing an important part of the American story,” said Richard Moe, the president of the National Trust, which during the past two years, with a $2 million donation from Lowe’s, has aided the renovation of 33 Rosenwald schools, including Pine Grove’s, as museums or community centers. States and communities have identified scores more in dilapidated condition.

Booker T. Washington’s emphasis on self-help and trade-oriented schooling — within the confines of segregation — was challenged as a surrender to oppression by black leaders like W.E.B. Dubois. But many white philanthropists of the era, like Rosenwald, were drawn to Washington’s strategy of helping blacks to better themselves rather than confronting the system directly, said Mary Hoffschwelle in “The Rosenwald Schools of the American South.”

Schumpert, the former teacher from Pine Grove, said she agreed that greater equality came only later, with integration. But she said that was not a realistic goal in the South of the 1920s. “Local whites on their own would not have built the school for us,” she said. “At least if you got educated, you could fight for yourself and start applying for jobs that were reserved for whites.”

The Pine Grove building’s restoration as a museum, with money from the National Trust, Lowe’s, the state and the Richland County Conservation Commission, is half done. Many of the one-time students hope the re-created school will help educate children — white and black — about their shared past.

“Sometimes we destroy our history,” said Cleoniece Rhett, 81, a younger sister of Schumpert. “You can tell kids about it, but they appreciate it better when they see it.”