Can a focus on humanities get you into med school?

Published 5:00 am Thursday, August 5, 2010

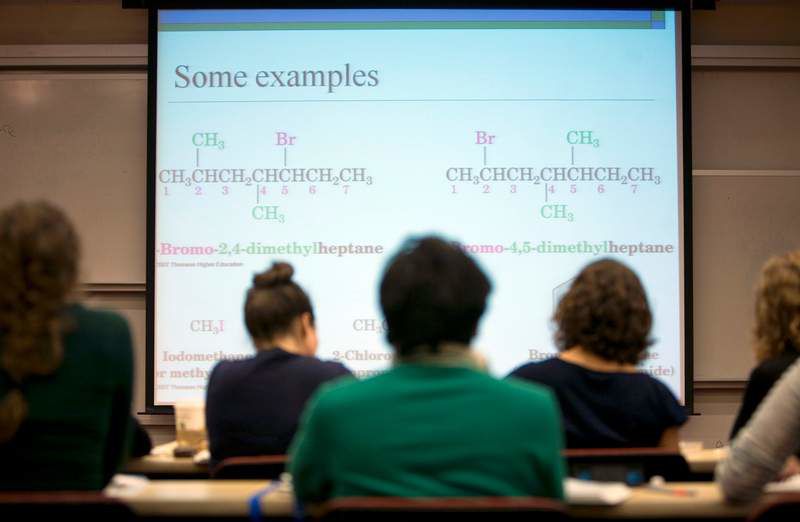

- Organic chemistry is among the more traditional med school subjects studied by students in Mount Sinai’s humanities and medicine program, but they take an abbreviated course in the summer.

For generations of pre-med students, three things have been as certain as death and taxes: organic chemistry, physics and the Medical College Admission Test, known by its dread-inducing acronym, MCAT.

So it came as a shock to Elizabeth Adler when she discovered, through a singer in her favorite a cappella group at Brown University, that one of the nation’s top medical schools admits a small number of students every year who have skipped all three requirements.

Until then, despite being the daughter of a physician, she said, “I was kind of thinking medical school was not the right track for me.”

An ongoing debate

Adler became one of the lucky few in one of the best-kept secrets in the cutthroat world of medical school admissions, the Humanities and Medicine Program at the Mount Sinai medical school in New York City.

The program promises slots to about 35 undergraduates a year if they study humanities or social sciences instead of the traditional pre-medical school curriculum and maintain a 3.5 grade-point average.

For decades, the medical profession has debated whether pre-med courses and admission tests produce doctors who know their alkyl halides but lack the sense of mission and interpersonal skills to become well-rounded, caring, inquisitive healers.

That debate is being rekindled by a study published July 29 in Academic Medicine, the journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges.

Conducted by the Mount Sinai program’s founder, Dr. Nathan Kase, and the medical school’s dean for medical education, Dr. Robert Muller, the peer-reviewed study compared outcomes for 85 students in the Humanities and Medicine Program with those of 606 traditionally prepared classmates from the graduating classes of 2004 through 2009, and found that their academic performance in medical school was equivalent.

“There’s no question,” Kase said. “The default pathway is: Well, how did they do on the MCAT? How did they do on organic chemistry? What was their grade-point average?

“That excludes a lot of kids,” said Kase, who founded the Mount Sinai program in 1987. “But it also diminishes; it makes science into an obstacle rather than something that is an insight into the biology of human disease.”

Some surprising results

There are a few other schools in the U.S. and Canada that admit students without MCAT scores, but Mount Sinai appears to have gone furthest in eschewing traditional science preparation, said Dr. Dan Hunt, co-secretary of the Liaison Committee on Medical Education, the medical school accrediting agency.

The students apply in their sophomore or junior years in college and agree to major in humanities or social science, rather than the hard sciences. If they are admitted, they are required to take only basic biology and chemistry, at a level many students accomplish through Advanced Placement courses in high school.

They forgo organic chemistry, physics and calculus — although they get abbreviated organic chemistry and physics courses during the summer They are exempt from the MCAT. Instead, they are admitted into the program based on high school SAT scores, two personal essays, high school and early college grades and interviews.

The study found that, by some measures, the humanities students made more sensitive doctors: They were more than twice as likely to train as psychiatrists (14 percent compared with 5.6 percent of their classmates) and somewhat more likely to go into primary care fields, like pediatrics and obstetrics and gynecology (49 percent compared with 39 percent). Conversely, they avoid some fields, like surgical subspecialties and anesthesiology.

But what surprised the authors the most, they said, was that humanities students were significantly more likely than their peers to devote a year to scholarly research (28 percent compared with 14 percent). They scored lower on Step 1 of the Medical Licensing Examination, taken after the second year of medical school, which generally correlates with scientific knowledge. But overall, they ranked about the same in honors grades and in the percentage in the top quarter of the class.