‘Hyena man’ keeps the peace between humans, animals

Published 5:00 am Thursday, August 5, 2010

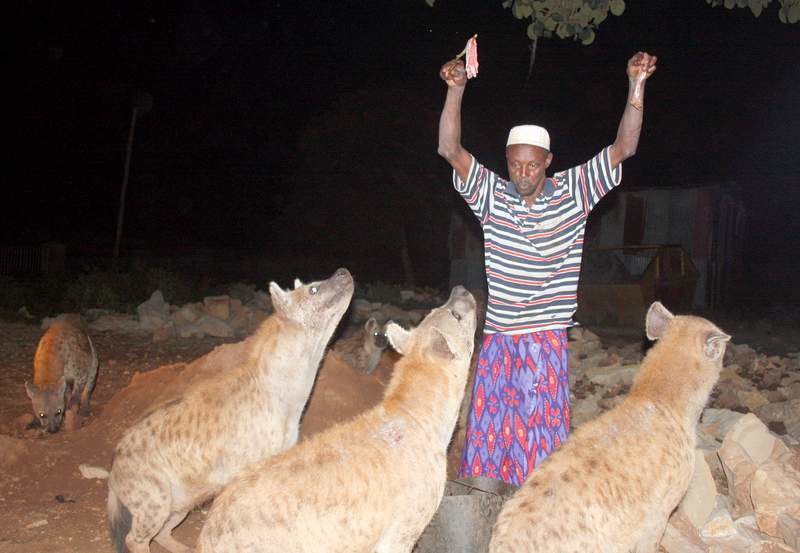

- Youseff Mume Saleh, of Harar, Ethiopia, has been feeding hyenas for years. As the animals slink toward his house at dusk, he calls to them by name.“We are family,” he explains.

HARAR, Ethiopia — Here in this medieval city in eastern Ethiopia, the humans and the hyenas are living in peace. The truce began two centuries ago (or so the story goes) during a time of great famine.

There was drought in the hills where the wildlife roamed, and hungry hyenas had sneaked into Harar and eaten people. Distressed, the town’s Muslim saints convened a meeting and devised a solution: The people would feed the hyenas porridge if the hyenas would stop their attacks. The plan worked, and a strange, symbiotic relationship was born.

City leaders went on to create holes in the sand-colored stone walls that surround Harar to give the hyenas nightly access to the town’s garbage. And in the 1960s, a farmer started feeding hyenas scraps of meat to keep them away from his livestock.

That farmer was the first “hyena man.” Today the title belongs to Youseff Mume Saleh.

Lithe and quick, Saleh, who is unsure of when he was born but says he is in his early 50s, has high cheekbones, a pursed mouth and few words.

He lives just outside the city walls, near an ancient Muslim shrine built around the trunk of a splendid fig tree. His home sits on an old landfill, the ground sparkling with shards of broken bottles.

Saleh’s nightly feeding ritual has become an attraction for tourists, who hire guides to bring them here. He has grown accustomed to the flash of their cameras and the tips they slip him at the end of the night.

Although the money helps — Saleh has two wives and seven children to provide for — he insists that his custom is not motivated by profit. The hyenas have come to rely on him, he says, and he worries what might happen if he stops.

Across Africa, hyenas are reviled as baby snatchers and garbage scavengers, the villains of village folk tales.

But when they slink toward Saleh’s house at dusk each night — green eyes gleaming, boxy jaws looking so eager to snap — Saleh calls to them.

“Funyamure,” he coos. “Tukwondilli.”

When a stranger later asks why he has given the animals names, Saleh sighs.

“We are family,” he says. “You have to understand.”

’I had to see’

Last winter, an odd guest showed up at Saleh’s home.

He was an Australian paleoanthropologist, and he wanted to know whether he could spend time with Saleh while conducting research for his Ph.D. on the city’s unusual social dynamic.

“I heard about this place in East Africa where hyenas walk the streets with impunity,” Marcus Baynes-Rock, 42, says. “I had to see.”

Since then, Baynes-Rock has grown close to the family. On many afternoons, he and Saleh can be found relaxing in the dark cool of the hyena man’s one-room home. They lounge on pillows, talk about hyenas and chew khat, a local plant whose leaves provide a mild stimulant effect. (People in Harar like stimulants: The region’s major export is coffee.)

“Their relationship is just like humans,” Saleh says of the hyenas. “Some fear the other. Some respect the other. Also, they have leaders.”

Baynes-Rock nods. “Some are aggressive and some are passive,” he says. “Some are very bright; some are brave.”

Over the course of eight months, Baynes-Rock has become a kind of hyena man himself.

Each night, once the hyenas have dined with Saleh, Baynes-Rock grabs his notebook, dons his night-vision goggles and follows the pack as it slinks through the town’s narrow alleyways.

Last month he married a local woman named Tikist. When they first met at a cafe, she spoke no English, and he had not yet begun learning her native Oromo tongue. He wooed her with photographs of hyenas.

Each year during the Muslim festival of Ashura, the city celebrates the hyena-human peace that the saints arranged many years ago.

On that morning, people leave porridge and butter for the hyenas at the many shrines that dot the town. The hyenas’ reaction to the food is said to predict the new year.

If the hyenas clear their plates, the town should prepare for drought. If they spurn the porridge, danger is afoot. If they eat most of the food but leave some, the villagers can expect a prosperous year.

A close and sometimes tense relationship

Baynes-Rock has spent some time with Saleh’s competition, another resident who feeds a different pack of hyenas for an audience of tourists each night. But he dismisses him as “a businessman, not a hyena man.”

Once, in the middle of the feeding, the other man answered a call on his cell phone. Baynes-Rock says he just doesn’t respect the hyenas the way Saleh does.For millennia, hyenas have been some of man’s fiercest predators.

Many of the earliest human fossils, including some that were discovered in Ethiopia’s Awash river valley, have tooth marks that came from ancestors of hyenas.

“For millions of years we’ve been living alongside these animals and developing a fear of them as well,” Baynes-Rock says. “You can see it in people’s eyes when they see the hyenas at night. It’s a primal fear.”

So why not in Harar?

Abdul-Muheimen Nasser has some answers.

The city historian and overall eccentric — he’s the only man in town who wears a backward baseball cap on his salt-and-pepper afro — says that hyenas are like “a transmitting station” that communicates news from the spirit world to humans.

He says that at the time Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie I died while imprisoned in 1975, a woman who could communicate with the hyenas in town had predicted his death.

“The hyena is the go-between,” Nasser, 69, says. “He is like the CNN or the BBC.”