BlackBerry’s stance on security sows anxiety

Published 5:00 am Monday, August 9, 2010

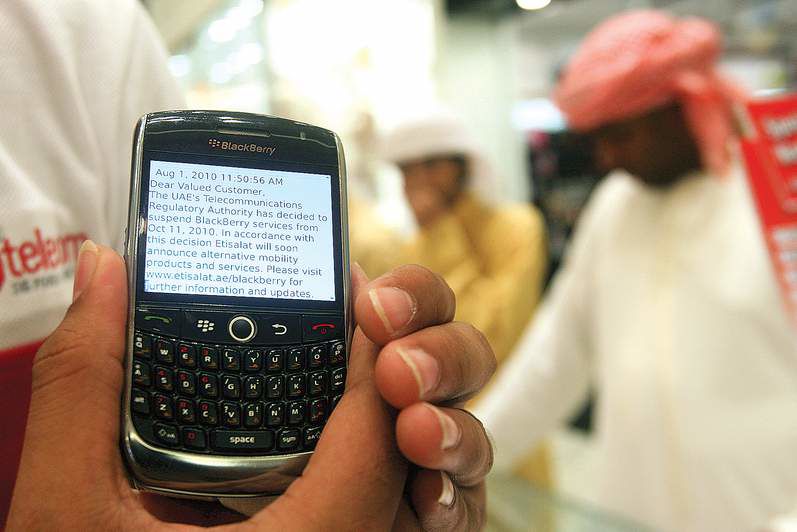

- A BlackBerry user at a mobile shop in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, displays a text message sent last week by his service provider notifying him of suspension of services. Officials from several nations, including the United Arab Emirates, India, Saudi Arabia and Lebanon, have announced or are contemplating bans on BlackBerry features.

The 2008 terrorist attacks in Mumbai heightened concerns in India over the government’s inability to eavesdrop on encrypted communications. In the United Arab Emirates, similar concerns escalated this year after a Palestinian operative was killed in a hotel in Dubai, possibly by a team from the Mossad, the Israeli intelligence agency.

In both countries, those concerns have crystallized into a battle with Research In Motion, the Canadian maker of BlackBerry smart phones, over whether and how their governments can gain access to messages that flow over the BlackBerry network.

And the dispute has put a spotlight on the challenges faced by many governments in monitoring communications services with global reach.

Eavesdroppers

Last week, the Emirates threatened to block BlackBerry’s e-mail and instant messaging services in that country unless RIM created back doors to allow officials to eavesdrop on the company’s customers.

Saudi Arabia has made a similar threat, and news reports over the weekend suggested that a deal had been made, but it was unclear what any deal might involve. Lebanon has also raised concerns. Indian officials have been negotiating with RIM over access to BlackBerry messages for a couple of weeks.

Although it is unclear precisely what these countries are asking for, one demand is for the same kind of access to BlackBerry’s encrypted services that they think the company already gives authorities in the United States and other industrialized democracies.

“I don’t think the concerns raised by India are out of the ordinary,” Sachin Pilot, the country’s junior minister for communications and information technology, said in a phone interview. “Most countries in the Western world have raised the issues and to the best of my information — and I am willing to be corrected — their concerns have been addressed.”

RIM officials flatly denied last week that the company had cut deals with certain countries to grant authorities special access to the BlackBerry system. They also said RIM would not compromise the security of its system.

At the same time, RIM says it complies with regulatory requirements around the world.

But the company, which is generally known for its secrecy, has declined to provide details on its discussions with governments or to explain how it complies with laws around the world that require communications companies to grant government agencies access to their systems for lawful intercepts.

This has kept alive suspicions in some foreign capitals and among computer security experts in the United States that RIM has made concessions to some countries.

Deals rumored

“There are all kinds of rumors that various deals have been struck around the world, including in the United States, but we don’t know what those deals are,” said Leslie Harris, chief executive of the Center for Democracy and Technology, which is based in Washington, and a board member of the Global Network Initiative, a coalition of companies and nonprofit groups that seeks to protect privacy and free expression on the Internet.

Speaking privately, several U.S. law enforcement and security officials would not say whether the government has a way to decrypt BlackBerry messages, explaining that they were reluctant to divulge whether any particular service posed difficulties.

But there has been little public sign of law enforcement frustration with BlackBerry en- cryption.

BlackBerry secure for companies but not employees

OTTAWA — In both form and function, a BlackBerry bought by a consumer and one handed to an employee by a corporation appear to be pretty much the same thing.

But the level of security afforded by the two smart phones could not be further apart. Data traveling to and from corporate phones is protected with a high level of encryption that the United States government also licenses from a subsidiary of Research In Motion, BlackBerry’s maker, to protect a wide range of its confidential communications.

By contrast, the consumer BlackBerrys offer no extra encryption, making them no more or less secure than other smart phones.

But encrypted or not, several Internet privacy advocates warn that the high level of data security provided by some BlackBerrys does not necessarily bring users a corresponding level of privacy. Indeed, a variety of software tools that RIM provides to corporations to monitor and record nearly everything employees do with their BlackBerrys potentially makes the devices powerful tools for surveillance by companies and governments.

For governments interested in monitoring their citizens’ mobile communications, BlackBerrys are tantalizing devices.

Uniquely, BlackBerrys consolidate all their digital dealings — Web browsing, e-mail and instant messaging — and then ship them to RIM’s computers through a network operated by the company. This effectively creates a complete record of a user’s mobile digital activity, which can be copied to servers that RIM provides to corporations and that also act as links to companies’ e-mail systems.

The frustration for some governments, however, is RIM’s encryption system. While neither RIM nor the countries it is battling, like the United Arab Emirates, has offered much detail about their dispute, it appears that the countries want RIM to turn over that data as well as a way to decrypt it.

But because individual BlackBerrys, not RIM’s servers, contain the digital key needed to unlock the encryption, most experts agree that RIM would be technically unable to fulfill this demand.

— New York Times News Service