Northwest travel: San Juan Island

Published 5:00 am Sunday, September 12, 2010

- Northwest travel: San Juan Island

FRIDAY HARBOR, Wash. — The last war between the United States and Great Britain was contested on a quiet island in the heart of the Salish Sea, midway between the Washington state mainland and Canada’s Vancouver Island.

Dubbed “The Pig War,” it percolated for more than 12 years — before, during and after the U.S. Civil War — until Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm I stepped in to resolve the dispute in 1872. Yet the only casualty was a renegade domestic boar, and the event today is remembered as proof that international conflicts can be peacefully resolved.

For the entire period of the dispute, American and English soldiers were posted at opposite ends of San Juan Island, 13 miles apart. To pass the time, the rival camps often socialized, competed in friendly sports and even feasted together on holidays. Clearly, this was no typical war.

San Juan Island National Historical Park today preserves both camps, as well as beautiful seascapes and a spectacular natural prairie. It is one of the highlights of a visit to the most populous and second-largest of the 172 named islands of the San Juan archipelago.

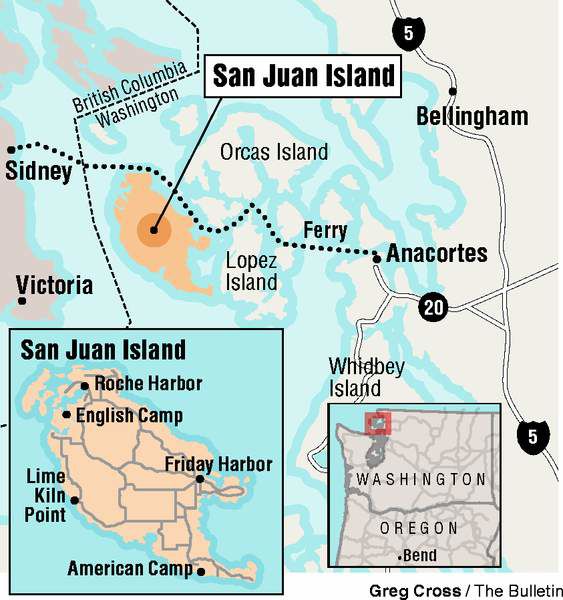

While there are ample roads to get around San Juan Island, visitors must take a boat to get there. Washington State ferries arrive and depart in Friday Harbor, the quaint county seat, numerous times each day from Anacortes, a port town located 20 miles off Interstate 5 at the end of state Highway 20. The trip takes between 60 and 80 minutes, depending upon intermediate stops (at Lopez or Orcas islands).

San Juan Island’s 8,000 residents, while isolated, have plenty to see and do. Just over 55 square miles in size — featuring farmlands and forests, coastal plains and rolling hills — the island is a popular place for bicycling. Its coves and inlets make it an ideal location for sea kayakers, who share the waves with resident orcas (killer whales) and other marine life. Friday Harbor’s Whale Museum is well-known, and the town has numerous fine-dining establishments and motels. Dozens of bed-and-breakfast inns are located around the island.

The Pig War

The roots of the Pig War may be traced to 1846, when Britain (then sovereign of Canada) and the U.S. established the international boundary at the 49th parallel “ … to the middle of the channel which separates the continent from Vancouver Island, and thence southerly through the middle of said channel. … ”

Confusion arose because there were actually two main channels: Haro Strait, west of San Juan Island, and Rosario Strait, on the east side of the San Juan group.

Each nation assumed the islands to be its own; Britain’s Hudson’s Bay Co. established a sheep ranch on San Juan Island as more than two dozen American settlers staked out their own turf.

In June 1859, a big black boar made the mistake of rooting around in a place it didn’t belong. The free-roaming pig belonged to Charles Griffin, manager of the British sheep ranch. It found a feast of potatoes in the garden of Lyman Cutlar, an American homesteader who did not take kindly to the invasion.

Cutlar shot and killed the pig. Griffin demanded more compensation than Cutlar was willing to offer. When Cutlar was threatened with arrest, he and other American settlers called for military protection.

According to historian Michael Vouri, chief of interpretation for the national park and the author of several books on San Juan history, the U.S. responded by sending 66 soldiers under the command of Capt. George Pickett, later a Confederate general.

The British countered by placing three warships in island waters. By August, the combined numbers had escalated to more than 2,500 soldiers. Yet both sides resisted firing a first shot, exchanging insults but no gunfire.

When slow-traveling news of the crisis reached the national capitals in Washington and London, leaders of both countries were aghast. U.S. President James Buchanan sent Gen. Winfield Scott, a hero of the Mexican War, to negotiate with Vancouver Island Gov. James Douglas. The two sides agreed to retain joint military occupation, with whittled-down forces, until final settlement of the dispute could be attained.

That state of affairs continued until 1871, when the United States was finally able to turn its attention back to international issues. As part of a treaty that addressed border issues related to the formation of Canada, the U.S. and Great Britain agreed to resolve the San Juan dispute through international arbitration. Chosen to mediate, Kaiser Wilhelm established a three-man commission that deliberated for nearly a year before deciding in favor of the U.S.

In November 1872, the British withdrew their Royal Marines. American troops were gone by July 1874.

American Camp

American Camp occupied both sides of the Cattle Point peninsula at the southeast end of San Juan Island. Facing across the Strait of Juan de Fuca toward the Olympic Mountains, the outpost was well-located to stave off possible naval incursions. Today, the 1,220-acre expanse is the larger of the two parcels of San Juan Island National Historical Park.

Park historian Vouri gave me a capsule account of the island’s past as we explored exhibits in the American Camp visitor center. Then I joined him on a hike through a section of the grounds. There isn’t a lot to see from a historical perspective; the original officers’ quarters and the laundress quarters (both restored in the 1970s) are all that remain from the 19th century, and neither is open for inspection.

Still visible nearby, however, is an earthen redoubt, a small fortification designed and built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers under the direction of 22-year-old Lt. Henry Martyn Robert.

Many years later, Robert — always a stickler for rules — published a small book on parliamentary procedure. It is still known today as “Robert’s Rules of Order.”

More impressive at American Camp is the expanse of prairie, which reaches for a couple of miles on both sides of the peninsula. Vouri said Native Americans harvested camas bulbs here as long ago as 2,500 years. Harpoon points and shell pendants have been recovered by archaeologists, along with souvenirs from the American military occupation.

“The long-term management plan at this park is a seamless blend of history and nature,” Vouri said. “Our goal is to restore this prairie to what it was before European settlement.”

An obstacle to that goal is an overpopulation of rabbits, introduced following the joint occupation. Their intricate warrens underlie much of the prairie acreage. The National Park Service has reported as many as 1,000 rabbits per hectare, or nearly a half-million in American Camp alone, yet they are protected within the park under federal law.

Birds of prey — the San Juans are home to 125 breeding pairs of well-fed bald eagles — can do only so much to control the population. Some islanders would have large numbers of rabbits humanely killed.

For the time being, that’s not going to happen. It’s hard not to spot the critters scurrying back to their holes as you stroll south from the visitors center, past the original site of the Hudson’s Bay Co. sheep farm, to Grandma’s Cove, a small but lovely beach famous for its tidepooling. A trail continues east along the bluff to South Beach, the island’s longest strand. Across the peninsula, on the Jake’s Lagoon Trail beside Griffin Bay, visitors often see small deer beneath the cedar-and-hemlock canopy.

East beyond American Camp, Cattle Point Road continues to a small residential area near the Cattle Point Light and an interpretive area focused on marine life.

English Camp and Roche Harbor

While American troops chose a bluff-top prairie for their encampment, the British Royal Marines established themselves on sheltered Garrison Bay, near the north end of San Juan Island. Today the sense of community is stronger here than at American Camp.

An original barracks building is now the unit’s visitors center; it features a small theater, where a short film about the Pig War is shown at regular intervals. Facing the old parade ground are a restored hospital, commissary and blockhouse. A formal English flower-and-herb garden has been replanted, and the site of the original officers’ quarters, on a hillside overlooking the grounds, is marked by a stone monument.

The hike to the top of 650-foot Young Hill is a steady mile-long ascent from the English Camp parking area, but it’s well worth the effort, if only for the view. The summit panorama features green fingers of wooded land stretching between deep-blue, fiord-like channels. The view extends west across Haro Strait to Vancouver Island, where Victoria, provincial capital of British Columbia, can be seen about 15 miles distant. Beyond, the snow-covered peaks of the Olympics rise across the Strait of Juan de Fuca. To the north, the hills of Canada’s Gulf Islands are easily visible beyond the northern San Juan Islands.

For the energetic, a three-mile trail circles Westcott Bay, famous for its oyster farm, and proceeds to Roche Harbor. Most visitors, however, prefer to drive to this second-largest community on San Juan Island.

Vacation homes and townhouses cluster around the charming Hotel de Haro, heartbeat of Roche Harbor Resort. Built in 1886, it became the community center for one of the Northwest’s largest lime quarries, a business that persisted for seven decades. Eight hundred people lived at Roche Harbor when the factory closed; the business was sold to resort developers in 1956.

Today the self-inclusive resort offers several choices of lodging, including the old hotel, and dining at three harborside restaurants. There’s a full-service day spa, a handsome 377-slip marina that accommodates international arrivals, marine outfitters offering everything from kayak rentals to sailing charters, and much more.

A stone’s throw from the resort is the open-air sculpture park of the San Juan Islands Museum of Art. It features more than 100 works, most of them for sale at prices ranging from $600 to $60,000.

Around the island

For many San Juan Island visitors, a prime destination is Lime Kiln Point State Park, 11 miles south of Roche. It’s known as a center for whale watching, especially from the bluff beside the 1919 Lime Kiln Point Lighthouse.

A well-maintained interpretive center describes the natural and human history of the area. Displays suggest which marine mammals to look for in the Haro Strait: whales and porpoises, seals and occasional otters. There’s no camping at this state park, but there are dozens of sites just up the road a couple of miles, at San Juan County Park.

In the center of the island is the Pelindaba Lavender Farm. With 20 rolling acres blooming in fragrant purple flowers through the summer and early fall, the farm has become nationally known for its large portfolio of hand-crafted lavender products. It also has a retail outlet in downtown Friday Harbor.

Indeed, Friday Harbor is the hub of all things San Juan. There are more than 40 restaurants in the little town, as well as a first-run theater, a bowling alley, high school tennis courts, and a concentration of lodgings. The San Juan Historical Museum includes eight separate buildings on an 1890s farm, including the original homestead and the first San Juan County Jail. Ask a curator to tell you about Joe Friday, a native Hawaiian who gave this town his name. Friday settled here after being employed as a sheepherder by the Hudson’s Bay Co.

Friday Harbor’s best-known attraction is the Whale Museum. Established in 1979 as the first American museum specifically devoted to whales, it has one-of-a-kind exhibits on the various marine mammals that inhabit the waters surrounding the San Juan Islands. Full-size whale skeletons hang from the ceiling of the exhibit hall, while the dozens of exhibits include a comparison of underwater sonar recordings and unique film footage.

The museum also operates a Whale Research Laboratory at Lime Kiln Point and a countywide Marine Mammal Stranding Network for the prompt rescue of any sea creature that may run aground.

In all of San Juan County, there are only 16,000 people. Half of them live on San Juan Island; another 5,000 make their homes on mountainous Orcas Island, the largest in the archipelago at 57 square miles. About 2,500 more are on Lopez Island.

That leaves fewer than 1,000 people on all other San Juan Islands combined. “A lot of people come here to get away,” admitted Robin Jacobson of the San Juan Islands Visitor Bureau. What better place than an isolated island in the middle of the Salish Sea?