The plan: Harvest fish, plants from the same water

Published 5:00 am Sunday, September 12, 2010

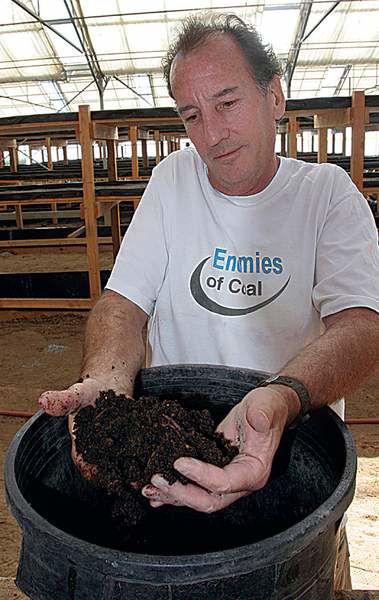

- Chris Newman will use worm castings to fertilize the watercress. The castings have a secondary effect of providing antibiotics for the fish when the water is recycled back into the holding pools.

CORRALITOS, Calif. — Chris Newman remembers when greenhouses ruled California’s Pajaro Valley and the state’s cut-flower business flourished worldwide.

Lamenting the industry’s decline, Newman, 58, sees a way to make use of the now-empty nurseries done in by foreign competitors and restore the glory of the once-regal greenhouse. It’s called aquaponics, a combination of aquaculture (fish farming) and hydroponics (growing plants in water), and Newman has set out to do it in a former rose-growing facility.

With his brother Tom and the help of neighbors, Newman has converted 14,000 square feet of greenhouse space into a system of stream channels, gravel beds and water pipes where he hopes to soon raise fish and grow vegetables commercially.

“With the cut-flower industry in the toilet and all those greenhouses sitting there, this is something I can do,” said Newman, who spent his childhood acquiring a fondness for his grandfather’s farm in the Pajaro Valley only to leave the area for a brief, but successful, career writing mystery novels in New York. “I’m pushing the envelope here, but I think this is something that’s bound to take off.”

Turning a hobby

into a business venture

Over the past few decades, aquaponics has become an increasingly popular backyard pursuit. But its commercial application has been limited.

Currently, says Rebecca Nelson, editor of the Wisconsin-based Aquaponics Journal, only a handful of aquaponics businesses operate in the United States. California Fish and Game wardens, who regulate the trade, say they’re not aware of any in the Santa Cruz area.

“I think in the next 10 years or so, you’re going to see more aquaponics farms in the U.S. and around the world,” said Nelson. “Farmed fish is really where we’re going as far as what we’ll have access to.”

The practice of aquaponics, Nelson explained, evolved from the desire to harvest fish, rather than put stress on dwindling wild fisheries, and grew into making use of the extra water by sowing crops. It’s a highly efficient means of both fish and vegetable production, she said, and its toll on the environment, compared with other ways of farming fish and vegetables, is minimal.

Newman believes he can capitalize on the high quality of the products and the fact that they’re ecologically sound.

“People here care about food ingredients and where they’re sourced,” he said. “Every 27-year-old kid in San Francisco now has a food blog.”

Newman, who has hired a marketing manager to develop his sales strategy, already has a name for his venture: “Santa Cruz Aquaponics.”

How it works

In his rented greenhouse, Newman has dug a series of 40-foot channels in which fish will soon swim. Above those are two stories of gravel beds where vegetables will grow — initially watercress but perhaps others in the future.

The next step is adding water to the system. The water will be pumped from the fish channels, where nitrogen and other plant-friendly nutrients accumulate, through the vegetable beds and then into an adjacent channel where duckweed will grow for fish food. Cleansed by the plants, the water then will flow back to the fish, closing a nearly self-sustaining loop.

Worm castings reared in nearby bins, Newman says, will be added to the system to serve as an antibiotic for the fish and to fertilize the plants.

Newman, whose new company logo features a blue tilapia, hopes tilapia ultimately will be his choice fish for production. It’s hardy and fast-growing, though current law prohibits farming the non-native fish in California. So Newman will begin with catfish.

In the meantime, he’s begun lobbying state regulators for a change in the law.

Officials from the Department of Fish and Game say they’re in the process of re-evaluating the tilapia ban, but because of the fish’s potential to escape and naturalize in local rivers and streams, they don’t know if the law will change.

“You can’t farm on the same kind of density with catfish (as tilapia),” Newman said. “You’re talking about half as much revenue.”

Newman has already sunk nearly $100,000 into his venture, and he’s eager to see a return.

“I know we’re going to do well,” he said. “And a lot of people here are rooting for us.”