Shoelacing variations

Published 5:00 am Thursday, September 16, 2010

- Shoelacing variations

Most of us learned to tie our shoes by kindergarten and probably haven’t given our shoe-lacing technique a second thought since then. So the vast majority of shoes, whether casual or athletic, get laced up in the same crisscross pattern.

But believe it or not, you won’t void the warranty on your shoes if you don’t hit every eyelet on the shoe in the same order. In fact, alternative lacing patterns can help fine-tune the fit of your running shoe and help address minor foot issues before they turn into major discomforts.

“Just because a shoe comes out of a box a certain way and that’s how we expect it to look when it comes out of the box, there’s nothing that says that’s necessarily the best way,” said Teague Hatfield, owner of FootZone, a specialty running shoe store in Bend. “Everyone should really mess with this stuff.”

With so many running shoe options, Hatfield said a good shoe store should be able to find a shoe that’s a good fit for your foot. But even with a wide variety of options, running shoes are much more standardized than human feet. Some people don’t even have two matching feet. Making adjustments to the lacing can help to fine-tune the fit of the shoe.

“What it tends to do is allow you to relieve pressure or secure a part of the shoe that would be difficult to do otherwise,” he said.

There’s a good reason that over time cross lacing has become the standard. Studies show it is one of the strongest shoe-lacing methods and provides fairly even pressure across the length of the foot. As a result, it works reasonably well for most people.

“If the shoe is fitting them well, if they have what we would consider a relatively average foot — not too high an arch, not too low, not too wide, not too narrow — they should do pretty fine with that,” said Dr. Karen Langone, president of the American Association of Podiatric Sports Medicine. “It’s the rest of us, sometimes we need to make a little tweak here or there.”

Traditionally, running shoes have had six pairs of eyelets arranged in parallel rows. (Many now add a seventh set off to the side.) According to Australian mathematician Burkard Polster, there’s actually close to 2 trillion combinations for lacing up a six-eyelet shoe. (His 2002 article in Nature spawned a cottage industry of scientific research into the mathematics of shoelacing.) Some of those lacing techniques would not be at all practical. Polster determined that there are about 43,000 practical ways to tie up your shoes, starting from the bottom and ending with a knot at the top.

Greater stability

Runners, on the other hand, can try a number of alternative lacing methods that still provide the stability needed for running but can improve the way the foot and shoe fit together.

The simplest variation is a technique known as a lace lock (see Fig. 2). It starts from the bottom with a standard cross lacing technique but at the second-to-last hole, the laces go straight up to the last hole on the same side, rather than crossing the tongue of the shoe again. That forms two loops through which the opposite ends of the laces are threaded, and then tied off normally.

The lace lock helps to tighten up the heel, preventing slippage, Langone said.

A lot of shoes now have an additional eyelet set off to the side of the sixth eyelet.

“So you can really pull that heel down a little bit more,” she said. “Women’s feet tend to be a little bit more narrow, and with a narrow foot, they can feel some heel slippage.”

Many runners simply ignore that extra seventh hole. But researchers led by Marco Hagen at the University of Duisburg, in Essen, Germany, recently tested the impact of the lock-lacing technique and concluded that could be a mistake.

They asked fourteen runners to test a pair of Nike Pegasus running shoes, trying four different lacing techniques. Two were standard cross lacing, one at normal tension and one extra tight; and two used lock-lacing techniques, one using all seven holes, and one creating a loop through the fifth and seventh holes, but skipping the sixth.

The runners rated the two lock-lacings and the extra tight cross lacings as the most stable, and rated the lock-lacing skipping the sixth hole as the most comfortable. The researchers also inserted sensors that could measure how much pressure was being exerted on the top of the foot with the various lacing techniques. Skipping the sixth eyelet results in significantly lower pressures on the top of the foot.

“The use of the often ignored/forgotten higher seventh eyelet that is slightly shifted to the lateral side has a remarkable effect and has been underestimated so far,” the researchers concluded.

In short, skipping the sixth eyelet was the most comfortable and the most stable, with the lowest pressure on the top of the foot. It’s probably the single alternative lacing technique that every runner might want to consider.

Lock-lacing, however, only scratches the surface for alternative techniques.

“People usually get introduced to lacing techniques with a lace lock, which is kind of that classic thing that running stores and mom and pop shops tend to do,” Hatfield said. “I have to admit there are times when that can be a little bit of a cop-out. There are times when I think we should really be trying to find a shoe that fits a little bit better.”

Getting fancy

But Hatfield also admits that when staff suggest alternative lacing techniques, customers see it as an almost magical solution, an innovative approach to their particular problem borne out of experience and know-how that’s beyond the average runner.

Those alternative approaches can include skipping the crossover lacing in sections to avoid a hot spot, a bunion or some other cause of pain (see Fig. 3). Inserting the laces into the top of the hole, rather than up from the bottom, tends to clamp down on the laces at each eyelet, allowing for variable pressure at different parts of the shoe.

One particularly clever technique creates a pocket in the front of the shoe to protect an injured toe (see Fig. 4).

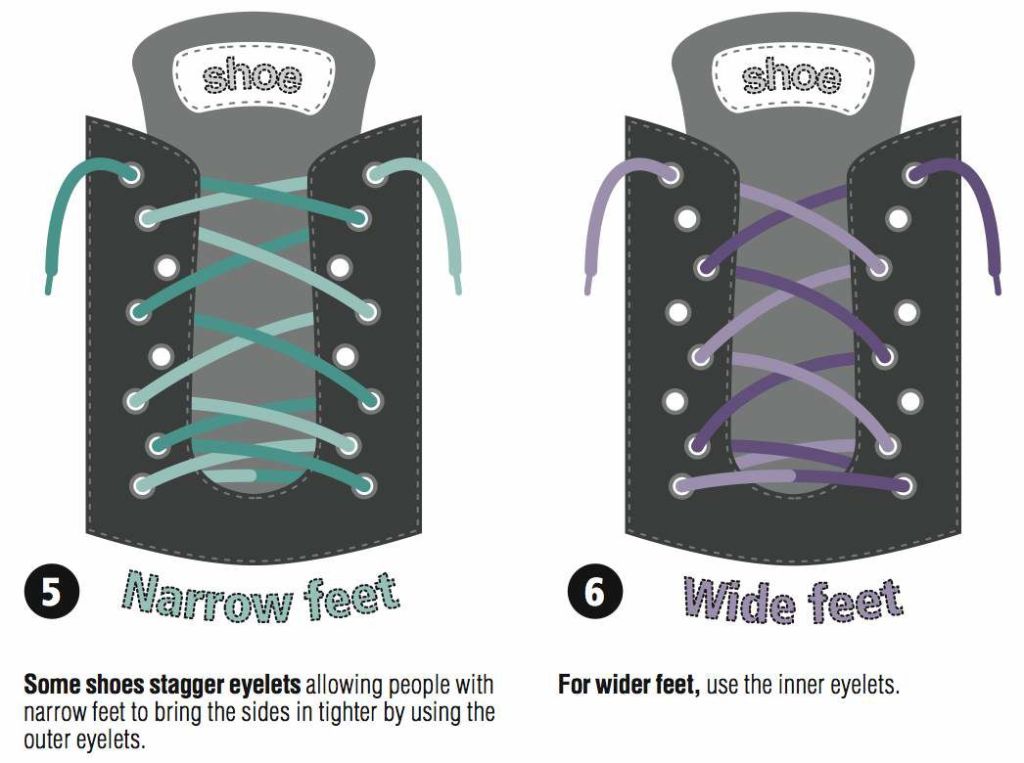

Shoe manufactuers are also coming up with new shoe designs that play with lacing techniques. Some shoes, for example, stagger eyelets rather than lining them up in a row. That allows people with narrow feet to use the outer eyelets to pull the sides of the shoe closer, and people with wider feet to give themselves more room by using the inner eyelets (see Fig. 5 and 6). Some running shoes have asymmetrical lacing patterns that lace up along the flatter, outside part of the foot rather than across the instep.

Good fit

Langone said most specialty running stores, particularly in running-obsessed towns such as Bend, have staff who run themselves and take pride in offering customers more than just the standard fitting.

“The retailers really seem to know their stuff,” Langone said. “Most of them are involved in the sport themselves, so they talk from the trenches, so to speak. Most of them have a really good knowledge base. It’s different when you go to the big box stores.”

If you can’t find an alternative lacing technique that relieves the pains you feel in your feet, you may want to track down a podiatrist or a physical therapist who can make sure you’re not dealing with a more serious problem.

“Runners are notorious for not listening (to their bodies),” said Chris Cooper, a physical therapist with Therapeutic Associates in Bend. “They think, ‘Oh, it’s going to go away, and then they’re in my office asking how to keep running, and they don’t want to hear, ‘Stop running.’”

Cooper said there are many lacing techniques that can be used to allow a minor injury to heal or help prevent problems from occurring. But many runners simply try to ignore their barking dogs.

“People either say, ‘Oh yeah, I know I’ll have aches and pains. It’s part of running,’ or they’re just going to be totally oblivious to it,” he said. “Usually what it takes is just listening to your body.”