What can China do for us?

Published 5:00 am Sunday, September 26, 2010

- What can China do for us?

BEIJING — Spend enough time with Chinese officials and economists, and you will hear a story about the Japanese yen in the 1980s.

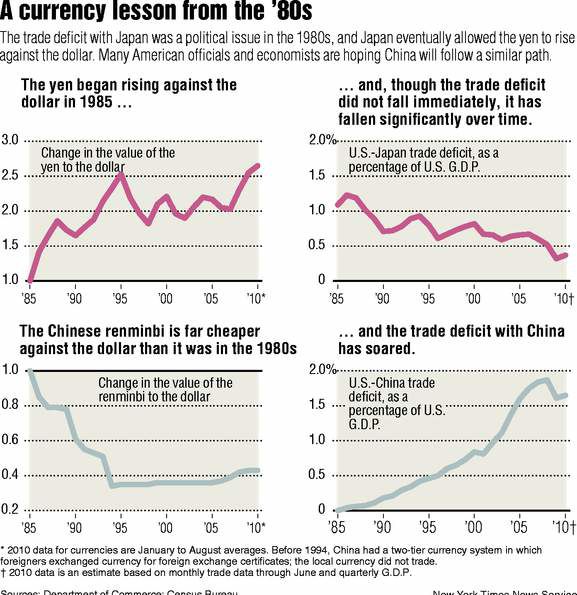

Back then, Americans were upset about Japanese imports flowing into the country, just as they are upset about Chinese imports today. So the United States pushed Japan to let the yen appreciate, thereby making Japanese imports more expensive and U.S. exports to Japan cheaper. Tokyo complied, and the yen surged almost 50 percent from 1985 to 1987.

Yet the imports kept coming. The trade deficit with Japan actually widened to $108 billion in 1987, from $94 billion in 1985. The rising yen wasn’t enough to halt the growth of companies like Sony and Toyota. They had too many advantages, including lower labor costs.

The moral of the story, in the Chinese telling, is that even a sharp rise in China’s renminbi wouldn’t necessarily do much to help the U.S. economy.

“Renminbi appreciation may not have a big impact,” Fan Gang, an economist and former government adviser, said last week at a meeting here with U.S. economists and policymakers, “or an impact at all.”

And it’s true that a stronger renminbi would not be a quick fix for our economic problems, as appealing a notion as that might be. The yen isn’t the only parallel here. The renminbi itself rose 21 percent against the dollar from 2005 to 2008, and the trade deficit continued to widen.

But there is also no question that China’s currency remains undervalued, probably by 20 percent or so.

The economics are simple enough. The huge demand for Chinese goods should be driving up the price of its currency, but Beijing has been intervening to prevent that. Getting China to stop will be crucial to correcting the global economy’s imbalances. A stronger renminbi will help China’s people — many of whom are hungry for better living standards, to judge by the recent labor strikes — buy more goods and services, and it will also help the rest of world produce more. But change is not going to happen overnight.

China’s Communist Party has had a very good 20-year run by making incremental changes and then watching the benefits accumulate over time. Realistically, that may be the best we can hope for with the renminbi.

It also happens to be the ultimate moral of the story about the yen — even if Chinese officials tend to leave that part out.

Two reasons

At first glance, it seems that a big change in an exchange rate should have an immediate impact. Certainly, it has some impact. The 1980s trade deficit with Japan would have grown even more rapidly had the yen not risen.

But there are two main reasons a stronger renminbi probably will not lead to a rapid hiring increase in the United States.

The first is that China and United States aren’t the only two countries in the world. Many products that we think of as being made in China, like the iPhone, are really just assembled in China. High-end parts often come from richer countries, like Israel or South Korea. Basic parts can be made in poorer countries, like Vietnam.

The entire value of the product counts toward the trade deficit between the United States and China. A stronger renminbi, however, would affect only the portion of the work done in China. And if the renminbi rose enough, some of this work would simply shift to a country like Vietnam (where per capita income is about $3,000, compared with $6,500 in China). Such a shift wouldn’t help close our overall trade deficit.

Chinese officials sometimes go so far as to suggest that the value of the renminbi makes little difference. That’s wrong. China’s economy is now large enough that its currency matters. But the issue is more complicated than it first seems.

The second reason not to view the exchange rate as a cure-all is that economies, like battleships, tend to turn slowly. Companies rarely move production in a matter of weeks. If they are using a Chinese supplier, it is often cheaper to stick with that supplier for a while, even if costs rise, rather than find a new one in another country.

The car business makes for a good example of what might change and when. The industry may not seem typical of the China story, because it has more to do with U.S. exports than Chinese imports. But exports probably matter more for U.S. jobs anyway, given that low-end toy manufacturing in Guangdong province isn’t moving to Alabama or Michigan.

Like other first-time visitors to China, I have been struck by the number of Buicks on the roads here. In one Beijing traffic jam, three Buick minivans were idling in the lane next to mine. When was the last time you were surrounded by Buicks?

With a stronger renminbi, you could see how carmakers might draw the dividing line in a different place, especially as the Chinese car market grows. The highest-margin vehicles would no longer be the only ones that could support the higher labor and shipping costs — not to mention China’s 25 percent vehicle tariff.

Already, U.S. exports to China are a big deal. They are on pace to equal about $83 billion this year, up from $68 billion last year and $21 billion a decade ago, adjusted for inflation. As a point of reference, $10 billion of gross domestic product equals about 80,000 jobs on average. So every extra $10 billion of goods sold to China is like its own little stimulus program.

Like any other stimulus, this one will require some politics — namely, pressuring China and negotiating with it. Companies will have to make clear, as General Electric, Microsoft and others have begun to, that their growth in China depends on the government taking property rights seriously and being more open to foreigners.

The long view

The United States and other countries, meanwhile, will have to look for any possible leverage to reduce tariffs and other barriers and push up the renminbi. China is eager to buy advanced technology, for example, and not all the items on the United States’ forbidden list are truly matters of national security. The Obama administration has started to prune this list.

Then, of course, there are those bills before Congress ominously threatening to put new tariffs on Chinese imports. The bills have definitely gotten China’s attention. If anything, they are a hotter topic in Beijing than in Washington, filling state-run newspapers and broadcasts.

The tricky part now is using the credible threat of tariffs to force a faster rise in the renminbi — which is up only 1.6 percent since 2008, mostly in the past two weeks — without setting off a trade war that would cost jobs in both countries.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can see the real lesson of that story about the yen is that success can take time. The yen has continued rising, gradually, since the 1980s and even after its fall in the last week is still more than twice as high versus the dollar as in 1985. Not coincidentally, the trade deficit with Japan, as a share of the economy, has shrunk 66 percent.

This is the path that rising economic powers, from Germany to the United States to Japan, have taken before. They start as exporters and then build up a thriving domestic economy. (Japan, alas, hasn’t been so good at the second part.) It’s the path China needs to take now, for the sake of its citizens and for the world.

The currency move of the past couple of weeks is a good start — so long as it continues.