Experiment puts writer at the airport for a week

Published 5:00 am Sunday, October 3, 2010

- Experiment puts writer at the airport for a week

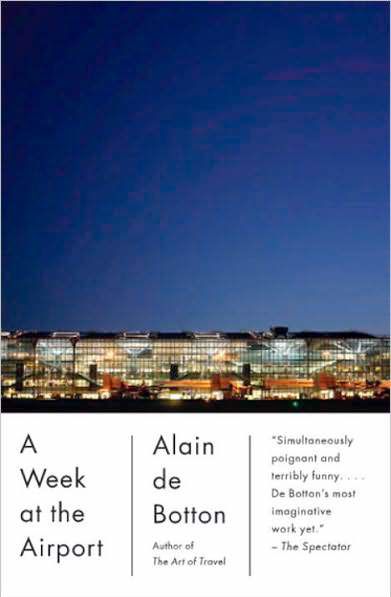

“A Week at the Airport” by Alain de Botton (Vintage Books, 112 pgs., $15)

Invited to spend a week as writer-in-residence at Terminal 5 of London’s Heathrow Airport, Alain de Botton has not just written a thoughtful book about the experience. He’s also written one that’s bemused, witty, philosophical, occasionally even a little nutty.

In “A Week at the Airport,” de Botton walks around the complexities and contradictions of airport life and the airline industry like someone walking around a Boeing 777 on the runway, both admiring and fearing its power.

BAA, the owner of Heathrow, placed few restrictions on de Botton, the Swiss-born, London-based author of “How Proust Can Change Your Life” and “The Art of Travel.” In a characteristic passage on this good fortune, he writes:

“I felt myself to be benefiting from a tradition wherein the wealthy merchant enters into a relationship with an artist fully prepared for him to behave like an outlaw; he does not expect good manners, he knows and is half delighted by the idea that the favoured baboon will smash his crockery. In such tolerance lies the ultimate proof of his power.”

De Botton sleeps, not always well, in a nearby airport hotel, and eats most of his meals at terminal restaurants. He talks with passengers and employees — pilots, baggage handlers, security people, cleaners, chaplains, shop workers. He observes, and listens, and sometimes speculates about the lovers clinging before a departure or the father and child reuniting. Photographer Richard Baker supplements de Botton’s wit with a raft of evocative images.

He also explores many of the more than 100 retail outlets vying for the attention of visitors. Propelled by an inner tailwind of musings about airport shopping and mortality, he explains to bookstore manager Manishankar:

“That I was looking for the sort of books in which a genial voice expresses emotions that the reader has long felt but never before really understood; those that convey the secret, everyday things that society at large prefers to leave unsaid; those that make one feel somehow less alone and strange.

“Manishankar wondered if I might like a magazine instead.”

Rarely has a book made me laugh quietly to myself while reading as often as this one did.

Discussing the tensions experienced by David, a shipping broker and possibly a workaholic, as he prepares to leave for a continental vacation with his family, de Botton writes:

“He had booked the trip in the expectation of being able to enjoy his children, his wife, the Mediterranean, some spanakopita and the Attic skies, but it was evident that he would be forced to apprehend all of these through the distorting filter of his own being, with its debilitating levels of fear, anxiety and wayward desire.

“There was, of course, no official recourse available to him, whether for assistance or complaint. British Airways did, it was true, maintain a desk manned by some unusually personable employees and adorned with the message: ‘We are here to help.’ But the staff shied away from existential issues, seeming to restrict their insights to matters relating to the transit time to adjacent satellites and the location of the nearest toilets.”

De Botton does not shy away from problematic elements of contemporary air travel. In the break room for security staff, he chats up Rachel and Simone, who train airport employees in anti-terrorist measures and grenade safety maneuvers. Simone tells him about the attempted bombing of an El Al flight in 1986, when a Jordanian man hid Semtex explosive in his pregnant Irish fiancee’s bag, without her knowledge: “The incident forever changed the way security personnel the world over would look at pregnant women, small children and kindly grandmothers.”

He also visits the place, two stories below the immigration hall, where children are given a box of snacks and plastic animals in a playroom while their parents are grilled about their status or denied permission to enter the country.

De Botton frets about an impending chat with Willie Walsh, the CEO of British Airways. But then he finds common ground: “Considered collectively, as a cohesive industry, civil aviation had never in its history shown a profit. Just as significantly, neither had book publishing.”

They end up gushing mutually about the gigantic spectacle of the airport: “Sequences of planes waiting to begin their journeys, their fins a confusion of colours against the grey horizon, like sails at a regatta.”

The author worries that his book will appear “a modest and static thing” next to “the chaotic, living entity that was a terminal.” But both parties got good value from this experiment, and travelers now have a slim volume that will make a fine companion on their next journey.