In New York studio, it’s all in arm’s reach

Published 5:00 am Tuesday, October 26, 2010

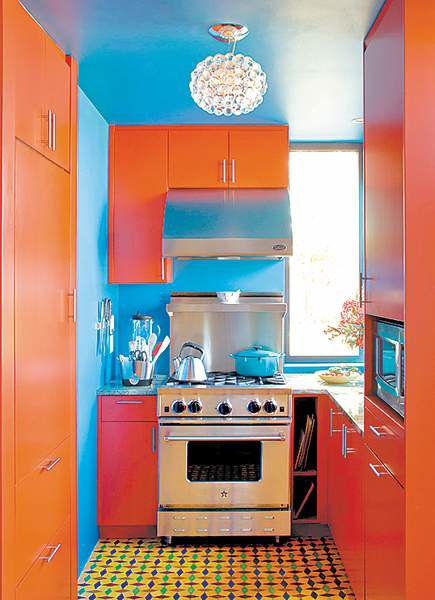

- The laundry facilities, refrigerator and dishwasher are all hidden behind red panels.

NEW YORK — Enid Woodward’s toenails are painted blue, a color you don’t often see on a mature woman. The walls of her tiny Manhattan penthouse are even more unusual — a strong sky blue, with blocks of red.

We are not talking pale colors here. This is color as an explosion of energy, color that could hurl you into the air if, by some magic power, color was given force: a comic-book blast of Superman blue and red.

It’s a bold choice, particularly since you cannot move from Woodward’s blue-and-red living room to, say, a bedroom painted a tranquil and self-effacing eggshell white. The living room is the bedroom is the dining room.

One big room

The apartment is one open space — and at 600 square feet, a very small space. And while many who live in small studios hide their beds in pull-down contraptions, Woodward does not. Her bamboo-backed four-poster stands large and proud, “a temple within a temple,” as she and her design team at D’Aquino Monaco call it.

“A friend of mine came in and said, ‘This is your bedroom, right?’” Woodward said. “She knew better, but she just couldn’t get her mind around it.”

She gestured with her hand at points about the room — the bed, the TV, the built-in desk. “I said, ‘No, this is my bedroom, this is my media room, this is my work room.’ The nice thing about a house tour is you can do it standing in one place.”

Woodward is 57. Her voice carries a touch of her native west Texas, though she has been in New York for more than 30 years. She was a founder of a dance company, Woodward Casarsa, and worked with it for the five years it existed in the early 1980s; she later worked as the on-tour physical therapist with the Alvin Ailey dance company for 10 years. She now has her own physical therapy office in Manhattan.

Woodward and her former husband, a financier and real estate broker, lived in the same prewar, Upper West Side apartment house where she now lives, in a large two-bedroom, two-bathroom apartment with a dining room. About 10 years ago, they bought the little apartment directly above them for $275,000. They planned to break through and turn the two into a duplex one day. When the marriage ended, Woodward, who loved the building and the neighborhood, got the apartment.

It had a cramped, dark bedroom and a tiny, walled-off kitchen. But it also had a very large asset: a wraparound terrace that was nearly the same size as the living space. Access was through a narrow living room door, though, and the terrace was only visible from two small windows in the living room, a small mullioned window in the bedroom, and another small window in the walled-off kitchen.

Still, for Woodward, who had gotten into gardening when she lived in Los Angeles, the terrace was a big draw. And she was not concerned about a small living space. What was important to her was that her home be a refuge, she said, where she could decompress and restore herself.

Design inspiration

To create that refuge, she worked with Carl D’Aquino and Francine Monaco of D’Aquino Monaco, an architecture and design firm. She gave them a few pictures she had pulled out of magazines: a cottage in England where everything was gray except for intense blue shutters; a bath house in Istanbul; Moroccan tiles.

She realized later that the team had also taken note of what she was wearing: a poncho a friend had knitted for her in burnt orange, a color that was echoed in the Burmese pots and bowls she had about the house. They had also listened carefully when she told them about her frequent spiritual retreats.

The renovation, which took 18 months from planning to completion, cost about $150,000, with another $15,000 for furnishings. The wall between bedroom and living room was knocked down, as was the wall in the tiny kitchen.

Windows were an important design element. The multi-paned window in the bedroom was replaced with a more modern single panel of glass; in the kitchen, a window was added and another enlarged, giving Woodward views of both sides of her terrace; and the living room wall adjoining the terrace was replaced with glass doors.

The cast-iron radiators dating back to when the building was constructed, in 1927, were removed. In the bathroom, a new radiator was cleverly concealed in a glamorous wall of mirrored storage; in the main room, radiators were hidden behind two broad steps leading to the terrace. Those wide steps, D’Aquino said, could also serve as additional seating.

The original steel entrance door to the apartment, however, was retained. With layers of paint removed, it has an antiqued look that works perfectly with Woodward’s collection of Etruscan pottery and handmade bronze sculptures from the Far East.

Providing the full kitchen, space for a washer and dryer, and the storage space Woodward wanted required the kind of meticulous architectural planning found on a yacht. Her bedside tables, the desk and the kitchen cabinets were custom built. The laundry facilities, closets, refrigerator and dishwasher are all hidden behind red panels.

But Woodward and her designers decided there was one thing they did not want to hide: the bed. She and D’Aquino had independently selected the same one — a bamboo-backed four poster, the Otto Canopy Bed from Gervasoni, which was a splurge for Woodward at $5,348. Using a hideaway was never considered; for those times when an exposed bed seems too intimate, drapes can be used to divide the room

The Moroccan tiles Woodward coveted line the floors of the bathroom and the kitchen and border the wooden floors in the main living space. For help with the terrace, Woodward worked with Karen Fausch, who owns the Metropolitan Gardener. There were, Fausch says, a great variety of plants and planters when Woodward brought her in — so many that the terrace felt hectic and overwhelming. Fausch added five trees to expand and define the space, placing two crab apples on either side of the entrance, with benches and birch trees around the area for privacy.

Inside and out, tied together

Most of the planters were replaced with fiberglass containers from Capital Garden Products. To tie outdoors to indoors, two were finished in the same blue as the apartment walls, as were the Bryant Park garden chairs. (The garden renovation required an additional budget: trees cost between $250 and $350 each, and planters ranged in price from $200 to $600.) Woodward kept the long reclaimed teak table from Country Casual that was already on the terrace. She also has boxes for lettuce and a Meyer lemon tree. (“I get just enough to make one very small lemon tart or one margarita,” she said.) Pine trees, which are visible from the bathroom, suggest the Japanese gardens she admires.

Like anyone who has conquered a small space, Woodward is aware of what she can and cannot acquire. She has room in her tiny kitchen cabinet for exactly six plates, six cups, six saucers, six glasses and six wineglasses, she said. And she has 12 inches of space in a closet for her “longs,” so if she gets a new dress or coat, something has to go.

Is there nothing she misses in terms of space?

“No, not at all,” she said. “I just feel like I have everything that I need, and I am constantly amazed at how convenient everything is. Everything just seems close at hand, because the place is so small. It seems like a great luxury to have it that way instead of a great liability.”