The photographer who went to war

Published 5:00 am Saturday, November 6, 2010

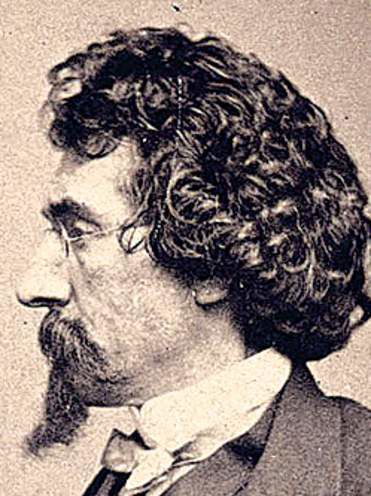

- Mathew Brady

In 1860, Mathew Brady was one of the world’s best-known photographers.

His book, “The Gallery of Illustrious Americans,” published 10 years earlier, had made him famous. Those who had sat in his studio and faced the large box on the wooden tripod included Daniel Webster, Edgar Allan Poe and Henry Clay.

So when Republican operatives wanted the perfect picture of presidential candidate Abraham Lincoln, they took him to Brady’s studio on Broadway in New York City. Brady looked at the tall, gangly man with the rugged, clean-shaven face. He pulled up his shirt collar so his neck wouldn’t look so long. He brushed down his hair and placed his hand on a book. Later, as Brady developed the photo, he retouched it so Lincoln’s facial lines wouldn’t be so harsh.

Brady produced a remarkable image. At that time most Americans hadn’t seen Lincoln, and his opponents had caricatured him as a wild frontiersman. Yet here he was — extremely tall, standing erect, an imposing gentleman in a long frock coat. The Brady photo was used for engravings and reprinted in the major weeklies of the day, Harper’s Weekly and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. It also appeared on a campaign button.

The same day he sat for Brady — Feb. 27, 1860 — Lincoln gave one of his most important speeches, the Cooper Union address. He spoke 7,000 words to an audience of influential businessmen, ministers, scholars and journalists. The speech was front-page news the next day. In an interview years later, very aware of his role in history, the photographer repeated what Lincoln reportedly said about the confluence: “Brady and the Cooper Institute made me president.”

Brady was born in Warren County, N.Y., in 1823. As a young man in New York City, he studied photography with Samuel Morse (in addition to inventing the electric telegraph and Morse code, Morse is credited with bringing the daguerreotype process from France to the United States). When Brady was introduced to daguerreotypes in the 1840s, photography was still a new art form and — at a time when most newspapers still relied on sketches — an extremely uncertain business venture. Nonetheless, Brady opened his first photography studio in 1844; by the following year he had won a national competition for the best colored and best plain daguerreotypes.

Portraits

, personality

He operated his studio like a painter’s workshop, assigning colleagues and apprentices to various tasks. Studio personnel operated the cameras after Brady set up the shot, a practice he may have adopted because of the poor eyesight that had plagued him since childhood. The photographer and his assistants posed their subjects. They became skilled at injecting personality into the images, much like formal portrait painters. Brady’s artistry was leavened with promotional acumen. As was the custom of the times, the studio’s photographs were reprinted on tiny cards called “cartes de visite,” making his work greatly accessible.

“Brady developed a reputation because of his quality and his marketing skills,” said Ann M. Shumard, curator of photographs at the National Portrait Gallery. “He was a good promoter and supplied images that could be reproduced. He adapted to the times.”

Edward McCarter, supervisory archivist for still pictures at the National Archives, concurred.

“Brady was the best-known entrepreneur of the day,” McCarter said. “You might get an argument on whether he was the best photographer.”

In 1858, Brady set up a second studio on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, across the street from the present location of the National Archives. He did his printing on the roof. He came to the city seeking greater proximity to the power brokers of the day, and his subjects included John Quincy Adams, Dolley Madison, Washington Irving, James Fenimore Cooper, Jenny Lind, Sojourner Truth, Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, William Cullen Bryant, Jefferson Davis, Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee. He even photographed the actor Edwin Booth and his brother John Wilkes Booth. His interest in documenting the era’s notables foreshadowed the art of celebrity portraiture.

“From the first I regarded myself as under obligation to my country to preserve the faces of the historic men and mothers,” Brady said in a 1891 article in the New York World. (Historians think the interview, one of the few given by Brady, is greatly embellished. It also includes a rare physical description of the aging photographer: “Mr. Brady is a person of trim, wiry, square-shouldered figure, with the light of an Irish shower-sun in his smile.”)

When the Civil War began in 1861, Brady decided to step outside the formal setting of his studio. Because he was the first photographer to actually go to a battlefield and document what he found there, he is widely considered the father of modern photojournalism. He later attributed his decision to destiny. After he returned from the first Battle of Bull Run, Brady recalled, “My wife and my most conservative friends had looked unfavorably upon this departure from commercial business to pictorial war correspondence, and I can only describe the destiny that overruled me by saying that, like Euphorion, I felt that I had to go.”

Legacy-minded

Brady seemed intent on establishing his legacy from the outset, in some cases even inserting himself into the studio’s wartime photographs.

“He’s in one taken at Gettysburg,” said Carol Johnson, a photography curator for the Library of Congress’s Civil War collections. Johnson said her staff still occasionally finds the photographer in the images, particularly as they are digitized.

Brady realized early on that the pictures were not mere memorabilia but were footnotes to history. In 1862, he displayed gruesome battlefield scenes taken by his studio colleagues Alexander Gardner and James Gibson in his New York gallery. The images of decaying corpses after the Battle of Antietam appalled viewers and galvanized the anti-war movement.

After the war, the demand for Brady’s work waned. Photography was changing rapidly, incorporating new equipment and techniques, and the public no longer wanted the Civil War images for which Brady was best known. A skilled promoter but an inept businessman, Brady had invested much of his capital in the studio’s war coverage. Ultimately it proved his financial ruin.

In late 1864, Brady began selling off his assets, including a half share in his Washington gallery. He sued his business partner when it fell into bankruptcy in 1868, then bought it back at public auction. But his affairs continued to spiral downward. The courts declared him bankrupt in 1873, and by 1875 his New York studios were closed. Brady petitioned Congress to buy his collection, which it did, for $25,000, in 1875. Despite his political associations, he failed to get a hall of prominent Americans — with his work as a critical source — started. His last known Washington address was 484 Maryland Ave. SW.

Brady died an indigent in New York on Jan. 15, 1896. His funeral was paid for by friends and a veterans association. He is buried in Congressional Cemetery in Washington.

Today, Washington is the epicenter of Brady scholarship. The National Archives and Records Administration, the Library of Congress and the National Portrait Gallery — where two walls of his work are on permanent display — house thousands of photographs and glass plates that have survived for more than 150 years. Taken together, they provide a haunting glimpse of the city and its nearby battlefields during the Civil War and an illuminating history of early photography.

That fateful sitting with Lincoln remains a pivotal departure point for the study of Brady and the Civil War. Even then, copies of the photo were scarce and quickly became collector’s items.

In a letter written on April 7, 1860, to a person requesting the Brady photo, Lincoln wrote: “I have not a single one now at my control; but I think you can easily get one at New York. While I was there I was taken to one of the places where they get up such things, and I suppose they got my shadow. … Yours truly, A. Lincoln.”