Replacing electrolytes

Published 4:00 am Thursday, November 11, 2010

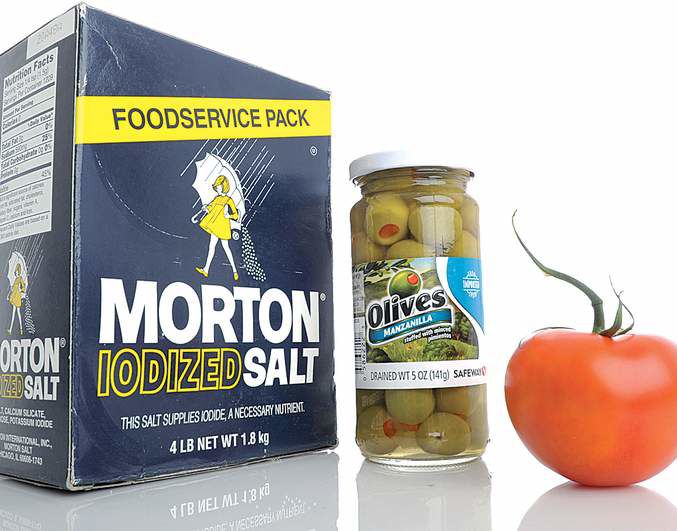

- Chloride: Helps to maintain fluid balance. Recommended daily intake: 2,300 mg. Good sources: salt, tomatoes, olives

The human body is a remarkable machine. Keep all of its various fluids and chemicals in the proper balance and it will perform all sorts of physical feats. But if that balance gets out of whack, the body can grind to a halt.

It’s why athletes from elite-level competitors to weekend warriors fret about replacing fluid, fuel and electrolytes after every event or workout. But while plenty of guidelines exist about replacing water and calories lost during activity, the notion of when and how to top off your electrolytes has been clouded by marketing and myth.

The result is that many fitness enthusiasts consume electrolytes when they don’t need them, while others inadvertently take steps that harm their electrolyte balance. The truth is electrolyte balance is inherently tied to your hydration levels, and unless you take the proper approach with fluids, you’re likely to negatively impact your electrolyte levels as well.

Body works

Electrolytes — primarily sodium, chloride, potassium, magnesium and calcium — are positively or negatively charged ions that conduct electricity. The body needs those ions to maintain the proper balance of fluid, to transmit nerve impulses and to contract muscles.

You can see why the athlete would be interested in keeping enough of those around.

For the most part, the kidneys manage your electrolyte supply, excreting excess when electrolytes levels are high and conserving supply when levels are low. The ability to maintain that balance, however, is stressed when you sweat.

Sweating is the body’s way of keeping cool. As your muscles work, they create heat, which is then transferred to the blood and the body core. To cool down, the body sends blood to the skin, where the heat can dissipate. This is why you often look and feel flushed when you start exercising.

As more heat is generated by the muscles, the body signals sweat glands to start pumping out sweat. As the sweat evaporates, the body cools. But that sweat also contains electrolytes, mainly sodium and chloride, that get left on the skin surface after the water evaporates. Sodium and chloride combine to make salt, which is why heavy sweaters can be left caked in salt when the sweat evaporates.

Quantifying losses

So how much sodium, chloride or other electrolytes do you lose while sweating? It depends on a number of factors. According to the American College of Sports Medicine, sweat rates and electrolyte concentrations in sweat can vary significantly from individual to individual. And, of course, how much you sweat also depends on the conditions outside, the clothing you’re wearing, and how hard you’re exercising.

You lose a lot more sodium and chloride than other electrolytes in sweat, six to seven times as much as potassium lost and more than 30 times the amount of calcium or magnesium lost. Sweat glands can reabsorb some of that sodium and chloride, but not enough to keep electrolyte levels from dropping over time.

Meanwhile, replacing the liquid lost while sweating is crucial. You’ll start to lose performance if you lose 2 percent of your body weight to sweat. At 3 percent, you start to cramp, and above 6 percent can result in heat exhaustion, coma or even death.

Runners can easily lose 1 to 2 percent of their body weight in an hour of running. If they don’t replace those fluids, performance will suffer, and in longer events, they could wind up with serious problems.

Concerns over dehydration, however, leave many runners drinking at every opportunity during races. But if they drink plain water, they further dilute their electrolyte levels. That can lead to a condition known as hyponatremia, or low sodium levels. Symptoms of hyponatremia — nausea, disorientation, muscle weakness — are similar to those of dehydration. In some cases, runners think they need to drink even more. It tends to be a problem in smaller, less fit marathon runners, who run slowly and sweat little but drink lots of water as they plod through their races.

Drink when thirsty

Experts now warn that concerns about hyponatremia have led many runners to cut back on fluids too much, swinging the pendulum back toward dehydration — so much so that the International Marathon Medical Director’s Association in 2006 had to revise its hydration guidelines urging runners to drink when thirsty.

“This advice seems way too simple to be true,” the group wrote in its revised guidelines. “However, physiologically, the new scientific evidence says that thirst will actually protect athletes from the hazards of both over- and underdrinking by providing real-time feedback on internal fluid balance.”

The group also recommended that for events lasting more than 30 minutes, if you’re going to drink, drink a sports drink. A sports drink provides carbohydrates for fuel and some electrolytes, but not solely for replacement purposes.

If sports drinks had the necessary amounts to fully replace sodium, chloride and other electrolytes lost through sweating, athletes wouldn’t be able to stomach them during competition. The marathon medical directors recommended sports drinks over water during races primarily because they reduce the chance of hyponatremia. Replacing some of the sodium content will delay the point at which sodium drops to problematic levels.

For a short run or bike ride, electrolyte levels are unlikely to drop enough to make a meaningful difference. It’s mainly a concern in longer events, the American College of Sports Medicine said in its latest statement on fluid replacement.

“The longer the exercise duration, the greater the cumulative effects of slight mismatches between fluid needs and replacement,” the group wrote. Over time those small deficits in water can add up to dehydration, while small deficits in electrolytes can lead to hyponatremia.

Finding the balance between over- and underhydration can be tricky, but most fitness experts use a 60- to 90-minute cutoff for when athletes need to be concerned about replacing fluids and electrolytes.

“A really safe and general rule of thumb is if you’re exercising over an hour, depending on your body type and size and then also how much you’re sweating, you might want to start drinking some electrolyte replacement every 20 minutes during the competition,” said Gregory Florez, a spokesman for the American Council on Exercise.

Florez said there are really only two options for replacing electrolytes on the move — sports drinks or gels. “Look for those that have very little or zero simple sugars, like sucrose or fructose, and more long-chain, slow burning sources of electrolyte replacement,” he said. “Those will spread out more evenly, and you won’t get that big buzz and crash.”

Recovery nutrition

After the race, however, the advice changes. Sports drinks like Gatorade or Powerade are designed primarily to top off hydration levels. They’re great for getting fluids and sugar into the body, but they’re not all that good at replacing electrolyte levels.

“The very small amount of sodium in a sports drink is added to enhance fluid retention, not to replace sodium losses,” said Nancy Clark, a registered dietitian and sports nutritionist. “You can easily replace the sodium lost in two pounds of sweat during a hard hour-long workout by enjoying a recovery snack of chocolate milk and a bagel with peanut butter.”

Otherwise a salty snack, such as pretzels, will have more than enough sodium and chloride to offset sweat losses.

Many athletes also worry about potassium because of a pervasive notion that low potassium levels will lead to muscle cramps. But potassium is lost through sweating in relatively small quantities, and most individuals store more than enough potassium in their bodies so that replacement is generally not a concern. Researchers in South Africa who took blood samples from triathletes found no correlation between muscle cramps and electrolyte levels.

If you’re concerned about potassium, “you can easily replace the 200 to 600 milligrams of potassium you might lose in an hour of hard training by snacking on a medium to large banana,” Clark said.

Most athletes should be able to get enough electrolytes from their regular diets. Levels of sodium, chloride and potassium are usually fully restored after the next meal.

Clark said she often sees runners who routinely drink Gatorade or other sports drinks before and after competition solely “for the electrolytes.” But she cautions that most of those people don’t need the additional help.

“You’re unlikely to need extra electrolytes to replace those lost in sweat,” Clark said. “If you exercise hard for more than four hours in the heat, such as marathoners, triathletes and even tennis players, you may benefit from replacing sodium.”

But unless you’re running a marathon, cycling 100 miles or otherwise exerting yourself for a long period of time, there’s no need to specifically load up on electrolytes. Clark said foods such as chicken soup or ramen noodles can help to hydrate and provide the sodium needed. Some extra salt after a long endurance event might help, but Americans generally get too much sodium in their diets as is.

Florez agrees that normal foods are the ideal source for electrolytes, but it may be necessary to get some supplemental help for more extreme pursuits.

“That’s what mother nature had in mind,” he said. “But mother nature also didn’t have in mind that we run 26.2 miles.”

Electrolyte supplements

For longer-duration events, athletes may want to consider specially designed electrolyte replacement products. Such products generally fall into three categories:

Electrolyte plus no calories

• Tablets and capsules often flavored with artificial sweeteners; useful for longer-duration activities in hot environments or for those with high-sodium sweat rates; should be taken with a sports drink

• Contain: 40-180 mg sodium, 23-50 mg potassium

• Examples: Nuun Active Hydration, Zym Endurance Tablet, Elixir, Powerbar Electrolyte Sticks, Thermolytes, Thermotabs, Lava Salts, Endurolytes, Sportaktive Portable Elecktrolyte Mix.

Electrolyte plus calories

• Sports drinks that provide electrolytes in a 4 to 8 percent carbohydrate solution; better for events lasting less than two hours

• Contain: 60-120 mg sodium, 15-43 mg potassium

• Examples: Accelerade, Accelerade Hydro, Clif Shot Electrolyte Replacement, Cytomax, G2, Gatorade, Powerade, Vitalyte

Endurance-specific electrolytes plus calories

• Designed to offset higher sweat losses; best for events lasting two to three hours

• Contain: 180-250 mg sodium, 10-107 mg potassium

• Examples: First Endurance Electrolyte Fuel System, Gatorade Endurance Formula, Luna Electrolyte Splash, Hammer Motor Tabs, Powerbar Endurance Sports Drink

Source: Shawn Dolan, American College of Sports Medicine.