Tax deal could be good for recovery, with a big ‘if’

Published 4:00 am Wednesday, December 8, 2010

- Tax deal could be good for recovery, with a big 'if'

If Congress does not act, the more than $3 trillion in tax cuts enacted under the Bush administration in 2001 and 2003 will expire Dec. 31, raising taxes on the average family by $3,000.

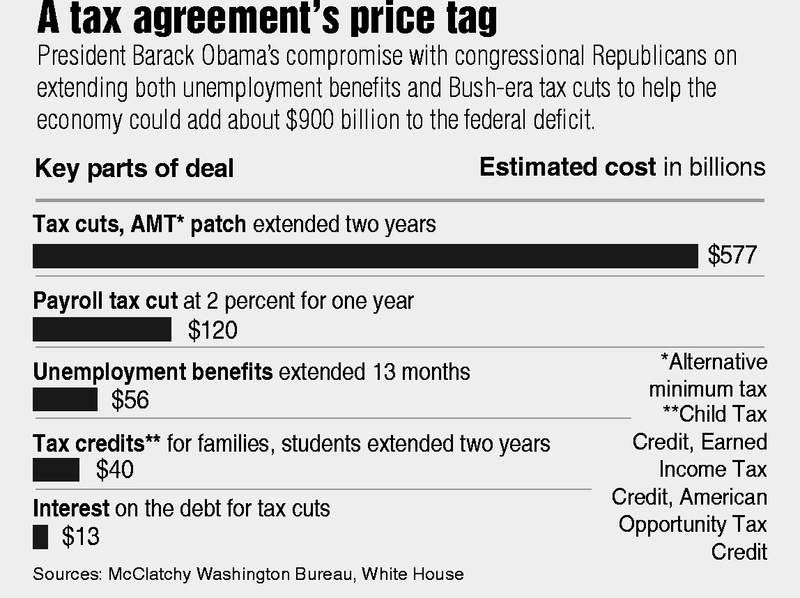

On the other hand, this week’s tax-cut compromise would contribute almost $1 trillion to the nation’s federal budget deficit over the next two years and add sharply to the mounting national debt, yet the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and mainstream economists cheered it.

Why? It’s a question of timing.

The deal, proposing roughly $900 billion in lost revenue, came days after a special bipartisan deficit-reduction panel warned the nation is on a path to fiscal ruin if it can’t get deficits and debt under control over the next decade.

The debt commission’s alarming warnings followed November’s midterm elections, when polls showed the deficit was a primary concern of tea party backers and independent voters. Yet President Barack Obama and congressional Republicans have teamed up to propose adding another $900 billion to the budget deficit and debt.

Confusing? Despite the apparent contradiction, most experts think adding to the deficit over the next year or two won’t worsen the problem if — and it’s a big if — Washington puts the nation on a path to tame the debt in ensuing years.

“If they can come up with a better system within two years, that may be entirely consistent,” said Diane Lim Rogers, the chief economist for the Concord Coalition, a bipartisan group dedicated to balanced federal budgets.

“It’s not going to work out well if this is just another kicking of the can down the road and two years from now we just extend them again. If it weren’t for the fact that these (debt) commissions have issued reports, I’d be much more cynical. It gives me more hope that two years down the road policymakers will not get away with the notion that this is an OK thing to do,” Rogers said.

Obama’s remarks

In a news conference Tuesday, Obama addressed the apparent contradiction between the long-term need to reduce budget deficits and his proposed deal, which would add to them for two years. He explained that the economy needs a jolt to push its slow-growth trajectory into a more robust recovery.

“The economy is not growing fast enough to drive down the unemployment rate,” Obama said.

He and his Republican partners are betting that a short-term rise in the deficit will help get the economy on a faster-growth path in two ways: eliminating fear that expiring tax cuts will result in higher taxes, along with reducing the wage tax and giving businesses other tax incentives to spend in 2011.

“One is the removal of a major obstacle to growth, which is the extension of tax cuts,” said Nariman Behravesh, the chief economist for forecaster IHS Global Insight. “Most economists thought that if taxes go up it could really hurt growth. And you really added some net new stimulus. That’s going to help growth a little bit, adding half a percentage (point) of growth for a few quarters. … With the economy still struggling, every little bit helps.”

There’s little evidence that extending the tax cuts for the wealthiest 2 percent of Americans would boost economic activity significantly, but pushing off the threat that tax rates might rise for two years helps reduce uncertainty.

That’s one reason business groups such as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce applauded.

The deal “will go a long way toward helping our economy break out of this slump and begin creating American jobs,” chamber Executive Vice President Bruce Josten said.

Other experts offered more qualified praise.

“I think the compromise is mainly about avoiding ‘contractionary’ policies, and not so much a new thrust to economic activity,” said Rudolph Penner, who directed the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office from 1983 to 1987. “The one exception to that is the payroll tax holiday.”

That proposal for a one-year wage-tax holiday would lower the 6.2 percent of income that all workers contribute to Social Security by 2 percentage points. That would cost the Treasury about $120 billion in lost revenue, according to White House estimates, which would be covered by borrowing, adding to the deficit. It’d replace the president’s Making Work Pay credit, a partial payroll tax credit this year for some workers that was heavy on paperwork.

“It’s bigger (than the current credit) and therefore probably gives you a net stimulus,” Penner said. “Whether it’s all worth it, I think, is an incredibly complicated question.”

Complicated not least because the deficit, which was viewed as a threat to the nation’s future just a week ago, would go up sharply over the next two years under the framework. That’s not such a big deal if Washington enacts the nearly $4 trillion in proposed savings that the bipartisan deficit-reduction commission’s report laid out Dec. 1, or something like them. The report recommends a radical overhaul of the tax code to create only three tax brackets and eliminate $1.1 trillion in tax breaks.

“It is so badly needed that if this was a trade for fundamental tax reform, I’d say it’s all worth it. But if nothing happens to improve the tax system as a result of this, then we haven’t accomplished much,” Penner said.

At his news conference Tuesday, Obama said he’d pursue a sweeping tax code overhaul in the years ahead, but first, he said, this deal is needed to stabilize the weak economy.

“The advantage of this is at least it’s not a permanent extension of any portion of the Bush tax cuts. My feeling has been the danger was in never letting go of the Bush tax cuts,” said Rogers, of the Concord Coalition.

Are the votes there?

Struggling to ensure that the package would win approval, the White House deployed Vice President Joe Biden to Capitol Hill in a bid to allay the concerns of Senate Democrats. But he failed to persuade many of his former Senate colleagues to line up behind the plan at a tense lunch meeting. In his pitch for support, he called it “a bad situation” but “a good deal,” participants said.

While many Democrats in the Senate and House raged against the idea of continuing George W. Bush’s tax policies for two more years — and some voiced serious concerns about adding $900 billion to the deficit — the package seemed likely to win approval provided that Republicans vote for it in big numbers.

Even with unanimous Republican support, which is not assured, at least 18 Senate Democrats would need to support the package to overcome a potential filibuster. About a dozen Senate Democrats have voiced a willingness to temporarily extend all of the Bush-era tax rates, given the weak economy. Aides said about 30 were firmly opposed, leaving 16 or so undecided.

The anger was rawer in the House, where Democrats met Tuesday evening to discuss the proposal. “I don’t think the president should count on Democratic votes to get this deal passed,” said Rep. Anthony Weiner, D-N.Y.

But if Democrats vote down the package, the incoming Republican majority would presumably approve it in January— perhaps after extracting further concessions from the White House.

What the agreement would mean for you

President Barack Obama’s tax bargain with congressional Republicans would extend Bush-era income tax cuts for all income groups for two years, but that’s not all the two sides have proposed. It is, in effect, a second economic stimulus. There is, for instance, a payroll tax cut for almost all American workers — amounting to a paycheck savings of $1,000 for a family earning $50,000. The deal also touches on:

• Unemployment insurance

• The estate tax • Tax credits

• Capital gains and the alternative minimum tax

Find a primer from The New York Times at bucks.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/12/07.

Obama to liberal critics: Learn to compromise

Before President Barack Obama’s Tuesday news conference, it was clear his willingness to compromise with Republicans on extending Bush-era tax cuts had left many liberal Democrats angry and dismayed. By the time the president stepped away from the White House podium 32 minutes later, it was equally clear the feeling was mutual.

Obama’s tone was alternately defensive and fiery. He dismissed his Democratic critics as “sanctimonious” and obsessed with staking out a “purist position.” He said they hold views so unrealistic that, by their measure of success, “we will never get anything done.”

“Take a tally,” the president challenged members of his party, seeming more riled by their criticism than by the opposition’s. “Look at what I promised during the campaign. There’s not a single thing that I’ve said that I would do that I have not either done or tried to do. And if I haven’t gotten it done yet, I’m still trying to do it.”

The remarks — along with the rebellion taking shape among liberals intent on letting the tax cuts for the wealthiest Americans expire — laid bare the fault line that for two years has separated Obama from some Democratic lawmakers and from the part of the party base that press secretary Robert Gibbs once dismissed as the “professional left.”

On Tuesday, Obama’s targets also included the GOP senators who insist that the tax cuts on household income above $250,000 remain in place. As he described his inability to get those lawmakers to “budge,” and his unwillingness to allow the cuts to expire for all Americans on schedule at year’s end, Obama invoked an unusual analogy — one that is unlikely to help the bipartisan outreach efforts to which he committed himself after his party’s drubbing in the midterm elections.

“I’ve said before that I felt that the middle-class tax cuts were being held hostage to the high-end tax cuts,” he said. “I think it’s tempting not to negotiate with hostage-takers, unless the hostage gets harmed. Then people will question the wisdom of that strategy. In this case, the hostage was the American people, and I was not willing to see them get harmed.”