GPS can take the guess work out of adventure

Published 4:00 am Friday, December 31, 2010

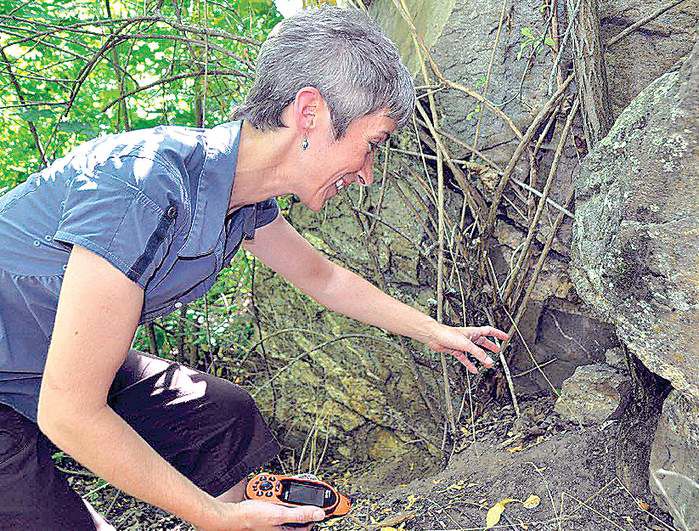

- Geocacher Lisa Breitenfeldt, of Spokane, Wash., uses a GPS unit to spot a geocache. For five years, she’s operated a business out of her home called Cache Advances, which markets products specifically for geocaching enthusiasts.

“Learning GPS is very much like using a VCR: Don’t be afraid to push buttons,” said Mark Beattie, assistant manager at Mountain Gear in Spokane, Wash. “If you can’t program something, look for a 12-year-old; they’re wiling to push buttons and risk it all.”

The benefits are worth the effort, as millions of GPS users have learned.

Trending

Hikers are logging the best cross-country routes from Point A to B.

Anglers are setting waypoints so they can return precisely to their big-lake honey holes.

Hunters are marking kill sites or GPS navigating to hunting blinds in the dark or fog.

Bicyclists and runners are plotting their routes to get details on distance and elevation gain for fine-tuning training.

Victims of backcountry emergencies have called in or delivered location coordinates for speedy rescues by searchers or pilots.

This is just a sampling of the uses for GPS.

Trending

In September, while off-trail exploring along the Shedroof Divide in the Salmo-Priest Wilderness in northeast Washington, I became confused as to which of the nondescript rounded peaks was which. To get oriented, I simply searched for Shedroof Mountain on my GPS device’s “where to” menu. An arrow pointed toward the destination and told me the exact distance I’d have to travel.

“A lot of people don’t even know that GPS means Global Positioning System,” Beattie said. “Some people are surprised that GPS hand-held devices navigate by triangulating satellite signals, not by cell phone towers.”

While new smartphones have GPS technology, they’re not nearly as precise as dedicated GPS units that range from $70 on up, experts say. And they may not work in the backcountry away from cell towers.

Most serious users are going to spend $180 to $500 for hand-held units with maps, display and features they’ll need in the field.

The typical new GPS user considers a GPS unit an adventure in itself.

Beattie had several teaching methods that help people get started.

First, he said, experiment with the unit in a park or close to home before heading out cross-country through the wilderness.

“I’m not a tech geek by any means,” said Beattie, as he tested a new Garmin Oregon earlier this year. Knowing how to operate one type of unit is no guarantee that you’ll immediately be able to operate another model efficiently, he said.

But after viewing online video instructions or reading the manual — a novel approach — and some trial and error, he soon began logging tracks and navigating to waypoints with ease.

John Higgins, a product expert and GPS guru at REI in Salt Lake City, also emphasizes trial-and-error practice before you really need it. In a story that appeared in the Salt Lake Tribune, he recalled testing a new unit in familiar backcountry. He tried to locate a waypoint which he knew from reading a map was only 2 miles away. The GPS was telling him the spot was 80 miles away.

He eventually realized the unit was on a “route by road” selection and not direct to point.

“We get a number of people who want to return them because they think the unit is inaccurate,” Higgins said. “It usually turns out to be a menu setting that is not appropriately entered, and it just takes a second to correct.”

Batteries are among the biggest pitfalls of relying on GPS devices. People who use vehicle-mounted GPS navigation sometimes forget their hand-held device is likely to run out of juice in a day.

I was pretty smug heading out for two days of trail research with fresh batteries and two spare pairs of rechargeable batteries. The second day out I learned that the spare batteries I’d recharged two weeks earlier had lost ALL of their charge.

As GPS technology has leveled off, manufacturers are creating more options to help distinguish their devices from the crowd. Cameras, phones, touch screens and MP3 players are appealing to some users, but the extras have a thirst for power that reduces battery life.

Beattie says users should explore the battery-saving options found on most new units, including shorter screen illumination times and automatic power-down.

The two most common points of advice experts have for GPS users:

• Carry a map for the area you’re exploring as a cross-reference and a backup to your GPS device.

“Knowing how to use a standard map and compass is an important part of your risk-playing and activity management,” Higgins said. “People think paper maps are obsolete, but a GPS can do nothing for you if it is dead. A paper map won’t just stop working like a GPS can.”

• Don’t forget to look around and take note of landmarks — and the scenery.

“I don’t live my life through technology,” Beattie said. “My cell phone is eight years old. GPS units are useful tools. But people can miss a lot of the outdoor experience and even get hurt if they’re focused on a GPS screen.”

Geocaching grows in popularity

The evolution of hand-held GPS units has spawned a legion of modern-day treasure hunters lured not by riches, but to the thrill of the hunt.

Geocaching, a game of hide it and seek it, has about 5 million fans around the world. They combine technology with outdoor adventure by posting or receiving clues on the Internet and heading out in terrain that ranges from inner city to wilderness.

“That’s the beauty of it,” said Lisa Breitenfeldt, an Inland Northwest geocaching guru and entrepreneur. “You can look for caches that might be on a corner down the street or one that takes days of hiking to reach. If you’re going to Europe, you can load coordinates before you leave to search out caches in, say, Paris.

“The thrill is finding a hidden cache that no one else knows about except you and other geocachers, even though thousands of other people might go right past it.”

Breitenfeldt started geocaching in 2002 for recreational relief as she pursued a master’s of technology management degree from Washington State University.

Her fascination with seeking caches soon developed into a business pursuit as she saw the demand for basic geocaching gear. In 2005, she launched Cache Advance with her first product: the Newbie Kit of basic items one needs to begin geocaching once they have their GPS unit.

Her Spokane, Wash.-based company, specializing in all things geocaching, has expanded its line to more than 200 products.

Her “cache cave” basement is like a toy-store warehouse with bins of gear and gadgets, such as a cache that looks like a bolt. “It has a hidden compartment and a magnet so it can be attached under a bridge railing or blend in at an industrial place,” she said.

Another cache looks like a rock.

She also sells the Geomate Jr. — a small easy-to-use, $70, geocaching-specific GPS unit, manufactured in Spokane by Servatron, Inc., also based in Spokane.

Not designed for navigating, the Geomate Jr. has a large database that holds up to 250,000 geocache locations. It will indicate caches closest to your location as well the difficulty, terrain rating and size of the cache container.

(Virtually all of the new and pricier GPS units useful to outdoorsmen, such as those made by Garmin and DeLorme, also have special geocaching modes.)

But the Newbie Kit — with waterproof notepads, pens, decryption keys, caches, trackable tags and more — is still her best seller. “I have trouble keeping them in stock,” she said.

Much of her business involves wholesaling through geocaching.com as well as retailing by Internet at amazon.com and around the world with her own Cache Advance site at cache-advance.com.

She also teaches geocaching and schedules visits to the Cache Cave by appointment.

— The Spokesman-Review