In California, a small fish is caught in a big fuss

Published 4:00 am Sunday, February 6, 2011

- In California, a small fish is caught in a big fuss

SACRAMENTO-SAN JOAQUIN DELTA, Calif. — When Peter Moyle began studying an obscure little Northern California fish in the early 1970s, he had no inkling of the role it would come to play in the state.

No one had paid much attention to the delta smelt. “They were just there,” recalled Moyle, then an assistant professor at the University of California, Davis, in need of a research topic. “We knew nothing about it.”

Nearly four decades later, the delta smelt is arguably the most powerful player in California water. Its movements rule the pumping operations of the state’s biggest water projects in the Sacramento- San Joaquin Delta. Efforts to stave off its demise have at times reduced water deliveries to 25 million people and 2 million acres of farmland, magnifying the impact of the recent drought and forcing farmers to fallow fields. Politicians harangue it and maneuver to gut the regulations that protect it.

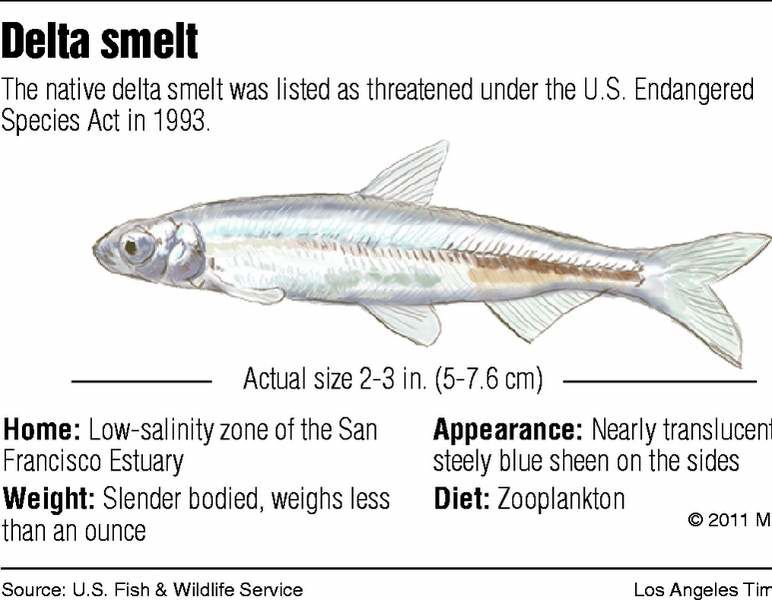

Why all the fuss over a puny creature — streaked in steely blue, redolent of cucumbers and no bigger than a woman’s little finger — that Central Valley congressmen and Fox News broadcasters belittle as a worthless bait fish and “a 2-inch minnow.” Why not just crank up the pumps and forget the thing?

Moyle, whose work helped earn the delta smelt a spot on the federal endangered species list in 1993, is philosophical at first: The American people have decided that we should not wipe species after species off the face of the Earth.

Then he gets more pragmatic. “If the delta smelt goes away, it’s not going to solve the problem” of California’s dependence on the ailing delta for a good measure of its water, Moyle said. He reels off a list of prized fish that use the delta and are also in trouble, such as Chinook salmon and green sturgeon. Help the smelt, he says, and we help them.

Bill Bennett is a former graduate student of Moyle’s who picked up his mentor’s research baton and passion for delta smelt. He champions Hypomesus transpacificus as a unique native whose fate is entwined with that of the West Coast’s largest estuary.

Drive the delta smelt and other natives into oblivion, he warns, and we will wind up with “the McDonalds and Wal-Mart version of California,” overrun with generic species from elsewhere. “I think people appreciate the real California rather than something they can get everywhere.”

Bennett, an associate researcher at UC Davis’ John Muir Institute of the Environment, is bracing himself against the wind as he speeds down the Sacramento River with a government research team on a chilly gray day to scout locations for a new smelt study. The crew was back on the river taking field samples in the rain at 3 a.m. Christmas Day.

Delta smelt exist “only here,” he says with an emphatic jab of his finger. “And they do something remarkable every year.” They hatch, mature, migrate up the delta to spawn in fresh water, and then die — all in a 12-month period.

Even under ideal conditions, a delta smelt’s existence is not easy. They have low fertility rates. For much of their life cycle, they favor a narrow zone of water with just the right salinity levels that shifts location in the delta according to freshwater flows.

Successful spawning requires a precise range of water temperature. One of their enduring mysteries is exactly where in the delta they spawn: Only one delta smelt egg has been discovered in the wild.

For the record, delta smelt are not minnows. They belong to the smelt family (Osmeridae), and are distant relatives of salmon. Like the San Francisco Estuary system it evolved in, the delta smelt is a young species, probably no older than 8,000 to 10,000 years.

The smelt’s ability to adapt to the complex conditions of the delta are a blessing and a curse, allowing it to develop as a distinct species but also limiting it to an area that has for decades functioned as a giant faucet for much of California.

“It’s extraordinarily well-adapted for the system the way it was,” Moyle said.

That is the core of the smelt’s problems, for today’s delta bears little resemblance to the fish’s original home. Drained, farmed, colonized by invasive species and used as a conduit to ship water from Northern California to the San Joaquin Valley and Southern California, the delta is an ecological invalid.

Scientists can’t say how close the delta smelt is to extinction, but the population has collapsed in the last decade to the lowest levels ever recorded. It’s possible that sometime soon the only place to find delta smelt will be in tanks at the UC Davis Fish Conservation and Culture Lab.