Carbon neutral in the park

Published 4:00 am Monday, February 21, 2011

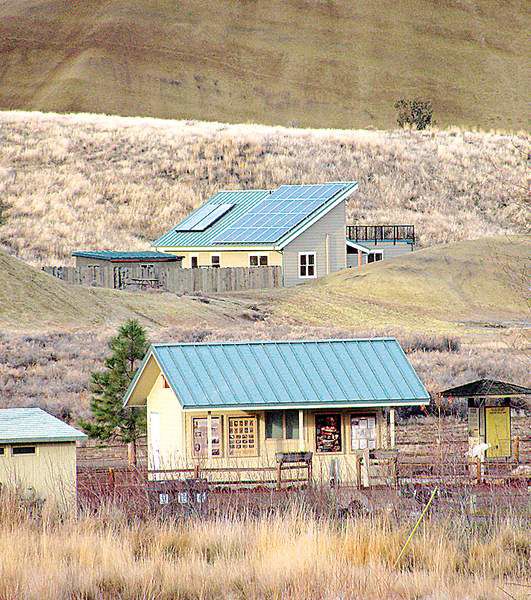

- All electricity for the ranger’s house, background, at the Painted Hills Unit of the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument is generated by the roof’s photovoltaic panels, which also produce enough to charge an electric vehicle and power a nearby visitor kiosk.

A small house with a sloped roof, tucked near the base of one of the earth-toned striped hills that gives the Painted Hills Unit of the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument its name, is more than just home to the park ranger.

It’s also a mini power-generating facility that puts more electricity into the grid than it consumes. Additionally, it demonstrates energy-efficiency possibilities for the National Park Service, according to NPS officials.

With solar panels on the house generating enough power for the home, a future electric vehicle for the park ranger and the visitor information kiosk, the Painted Hills Unit is now an energy-neutral unit of the monument, said Jim Hammett, superintendent of the Fossil Beds.

The National Park Service’s director has challenged parks to be as energy efficient as possible, Hammett said, and to try to make park operations carbon neutral — not burning any fossil fuels.

“That’s a very difficult thing to obtain,” Hammett said. “If we took and started with a baby step of a small unit, it seemed possible.”

The Painted Hills building is the first National Park Service house to be net-zero energy, said Stephanie Burkhart, spokeswoman with the agency’s Pacific West Region.

But another project, an intern center in the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, built around the same time last winter, was the first facility that was not specifically a house to meet the criteria, she said.

At the Fossil Beds, Hammett said he started looking at designs of houses that were net-zero energy a couple of years ago — not using any more power than that created through solar panels or other renewable resources.

His research led him to Ted Clifton with Zero Energy Plans in Washington state, who modified an existing plan for the Painted Hills ranger house, and came up with a house that produces its own energy, plus some extra.

“We had really the full support and encouragement of the park service to do all the little things,” Clifton said. “Many customers, they won’t quite pull the trigger to do all the things to get to zero energy.”

The key is to get the power use of the house down as far as possible, he said, noting that the Painted Hills house will use about 40 percent of what a normal house would.

“Then, what’s left doesn’t take much to run,” he said.

To get to a low electricity use requires things like measuring where the sunlight would come in from each window, he said, to see if rays would hit the concrete floor — which would absorb and store the energy — or simply hit a couch. It involves using a specialized, but still cost-comparable, type of framing with built-in foam insulation, and making sure all the appliances are the most efficient possible.

“All these things are out there, it’s all off-the-rack stuff,” Clifton said. “It’s just selecting the best stuff off the rack.”

The Painted Hills house is designed not only to generate all the energy its residents use, with solar panels for both electricity and hot water, but also to create extra power for transportation. With the 24 solar panels producing a little more than 7,000 kilowatts of power a year, Clifton said, there’s enough power left over to charge up a Chevy Volt electric car to drive more than 5,000 miles a year.

Building green and net-zero energy is possible even on a modest budget, he said, noting that he recently designed a 1,900-square-foot, three-bedroom home for about $240,000 — including enough solar power for the house and an electric car. But it could take more demand from customers before it catches on.

The Painted Hills house is about 1,000 square feet and cost about $200 per square foot to build. It was built by Kirby Nagelhout Construction Co., of Bend.

The park service is committed to making operations as energy efficient as possible, Hammett said. With so many resources potentially negatively impacted by climate change — such as Glacier National Park quickly losing all of its glaciers — it’s a key issue for the agency, he said.

“We view the national parks as sort of a canary in the mine,” Hammett said. “If the ecosystems in the parks go downhill, what does that say?”

The Painted Hills operation is small and doesn’t require much power to start with — just one house, an information kiosk that isn’t heated and the ranger’s vehicle. But the monument plans to buy an electric utility vehicle for the unit, Hammett said, and the operation is a step in the right direction.

“It was more symbolic than anything else, but it is very real,” he said. “We’ve made that operation of Painted Hills carbon neutral.”