Cardiac catheterization

Published 5:00 am Thursday, March 24, 2011

- Cardiac catheterization

Each year thousands of Americans undergo cardiac catheterization, a procedure where a thin plastic tube is snaked through an artery or vein into the chambers of the heart or the coronary arteries. It can be used to measure blood pressure within the heart or how much oxygen is in the blood. Doctors can inject dye into coronary arteries through the tube to map out blockages, or the procedure can be used to clear arteries with a balloon or prop them open with a stent.

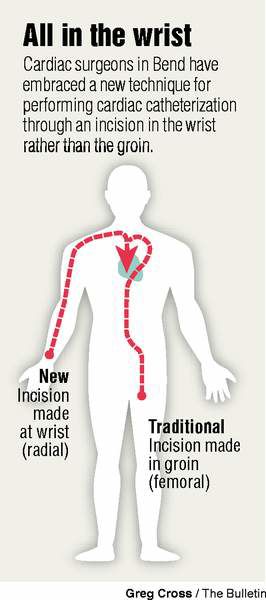

For the vast majority of patients, the catheter is inserted through an opening in the groin, requiring patients to lie still for hours after the procedure so the entry wound can heal. Over the past 20 years, however, some cardiologists have opted for an alternative entry point — the wrist.

Guiding the catheter through the radial artery in the arm, rather than the femoral artery in the groin, is more difficult for the physician but appears to have a much lower risk of complications and a much easier recovery for patients. Yet fewer than 10 percent of cardiac catheterizations in the U.S. are done with the radial approach.

Central Oregon is the exception. Cardiologists at St. Charles Bend perform radial catheterization 70 percent of the time, among the highest rates in the country. A 2008 study that looked at radial catheterization rates in more than 600 centers nationwide found that only seven facilities had rates higher than 40 percent.

“We were early adopters,” said Dr. Bruce McLellan, a cardiologist with Heart Center Cardiology in Bend. “We recognized the benefit for the patient, and we were willing to spend the time and energy to get good at it.”

Most cardiologists have been trained only in femoral access, and there’s a substantial learning curve when they start to go through the wrist.

“If you’ve trained only in femoral, you’re faced now with a decision: Do I want to frustrate myself for several months or a year, or do it this other way where I’m pretty good at what I do?” McLellan explained. “From an individual physician standpoint, that’s pretty easy. But you have to recognize the benefit and it’s not just for the patient, it really is for the physician as well.”

The major benefit is reducing the risk of bleeding after the procedure. With femoral access, doctors affix a cuff on the entry point that applies continuous pressure, allowing the wound to heal. If the patient moves too much or in the wrong way in the hours after surgery, the wound can easily reopen and begin bleeding internally. In worst-case scenarios, the bleeding might not be immediately evident.

“You can hide one or two units of blood in the groin going down back behind the pelvis without it being obvious. And the first sign that you have trouble is the patient is very uncomfortable with pain or they drop their pressure,” McLellan said. “You can’t hide much blood in your wrist. If it comes out it’s going to be squirting around or leaking around.”

Dr. Sunil Rao, a Duke University cardiologist and a staunch proponent of radial access, compared bleeding rates for femoral and radial catheterizations using a national databank of cardiac procedures. He found bleeding complications in 1.8 percent of procedures done through the groin, compared with 0.8 percent of procedures done through the wrist, a 58 percent lower risk.

In 2005, McLellan calculated that patients at St. Charles Bend had a 3.8 percent complication rate with femoral catheterization, compared with a 0.4 percent rate with radial access. (Local and national complication rates are not necessarily comparable due to the way the data is collected.)

And because bleeding after a procedure is associated with longer hospital stays, higher costs and an increased risk of death, it’s a meaningful difference.

With radial access, the doctor puts on a simple plastic strap that fastens like a zip tie, and the patient can literally walk out of the catheterization lab.

“They’ll be up and walking around, they can sit up and eat right after the procedure, which will make them happy,” McLellan said. “They’ll have to eat left handed, but I think most of them will take that, and then they will go home sooner.”

The procedure is almost always done through the right wrist, primarily because of the way cath labs are set up to accommodate right-handed cardiologists, working from the right side of the table. (Left-handed cardiologists are generally forced to adapt.)

The easier recovery also means a patient can have the procedure done in the morning and go home that night, eliminating the cost of an overnight hospital stay. That helped cut the cost of the procedure by an average of $290 in one study.

D.W. Halligan, 83, of Bend, had his first cardiac catheterization done in 1961 through the groin. He recalls the nurses putting a sand bag on his leg after the procedure to keep pressure on the entry wound. But in the past year, he’s had two more here in Bend, both through the arm.

“When it’s done through the arm, it wasn’t as uncomfortable afterward. There was very, very little discomfort afterward,” he said. “When it’s in your groin, when you move your leg, it interferes with your laying around or rolling over. It’s more difficult to avoid pressure on the thing inadvertently afterward.”

With his first procedure, he stayed overnight in the hospital, while with the two radial procedures he went home the same day. If he had to have another catheterization, he’d prefer the radial route.

“I think I’d ask the surgeon what’s best, but if I had a choice, I’d go for the arm,” Halligan said.

The technique does take a little longer, on average, extending the time the patient is exposed to X-rays that help the cardiologist find his way to the heart. But studies suggest that as doctors get more proficient with radial catheterization, the time difference is minimized.

Despite all the advantages, outside of Central Oregon, radial catheterization has been slow to catch on in the U.S. It’s more prevalent in Europe where radial access makes up 50 to 70 percent of catheterizations. A large, randomized, controlled trial under way since 2006 is expected to provide definitive results on whether radial access is the more effective approach. That could convince more cardiologists it’s the right way to go.

The Bend cardiologists, who have been doing radial catheterizations for more than 10 years, have made a concerted effort to shift towards radial access and have “strongly encouraged” cardiologists joining the practice to learn the technique and become proficient. Now more cardiology training programs teach the technique, so the learning curve may be eliminated for the next generation of cardiologists. And that could make radial access more the rule than the exception.

“I think it will happen with time. It’s more of a mental hurdle for a practicing cardiologist,” McLellan said. “But the patients who have had both will, hands down, say they prefer the radial.”