Sharing caregiving

Published 5:00 am Friday, March 25, 2011

- Sharing caregiving

The first signs of Alzheimer’s appeared more than two years ago while Doris Palmer still lived in her Prineville home. One morning she woke up and couldn’t remember how to make coffee. Another time, Palmer’s daughters realized Palmer had not been paying her bills.

The three adult siblings, who all bear a striking resemblance to each other and to their mother, live in Prineville and Powell Butte. They called a family meeting with their mother and their husbands.

“In the beginning we decided we’d always talk about things,” said Palmer’s oldest daughter, Callene Weatherson, 56. They decided that if they couldn’t make decisions unanimously, they’d vote, and the majority would rule. They had a lot to think about. Where would Palmer live? Who would help her? What help would she need? What did the future hold in store for all of them?

The sisters are poster children for a new, free, online program called the 50-50 Rule, which is aimed at siblings negotiating the care of an aging or ailing parent. The website (www.solvingfamilyconflict.com ) offers tips from experts on prevalent issues and discussions of real-life situations. The “50-50” refers to the age when siblings are likely to start caring for their parents, and the need for them to share in the care, 50-50, to prevent sibling strife and resentment.

Palmer’s daughters agreed that their mother, who is now 74, couldn’t live alone in her house anymore, with all that lawn maintenance and kindling splitting and snow shoveling to do.

With Palmer’s involvement, they chose an affordable apartment in Prineville where her neighbors would help watch out for her. And they hired an in-home caregiver.

In-home care

Home Instead, the local franchise of a global company, is one of many in-home service providers in the region that provides a range of services that aim to keep seniors living independently as long as possible. They’ll drive a senior to the store or do the grocery shopping for them. They can help with bathing, house cleaning or socialization. It can be a one-time job, or an ongoing, regular service.

Palmer was hesitant to bring a stranger into her home. She didn’t know what to expect. Her daughter Debra Peterson, 55, said they all worried about the potential of a caregiver to swindle or hurt their mother in some way. But they chose Home Instead, a bonded and insured company, and requested a caregiver whom Palmer already knew personally.

The goal was to protect Palmer’s safety, and for her “to stay as independent as possible for as long as possible, and let her make all the decisions she can make,” said Palmer’s youngest daughter, Sheryl Crawford, 50.

The caregiver visits three times a week and helps Palmer shower so she doesn’t slip and fall. She cleans, cooks and does laundry. Palmer’s living space improved dramatically, one daughter said.

Having a caregiver do the work allowed the daughters to spend time with their mother in more enjoyable and loving ways.

“We sisters try to keep what we do a little more lighthearted,” Weatherson said. “I especially get resistance if I try to get her to bathe. If it’s the caregiver she’s paying she doesn’t give them near as much grief.”

Experts say seniors don’t generally like upsetting the parent-child balance in their relationships.

Weatherson can relate: “She still tells me, ‘I’m the parent here.’ ”

Palmer eventually appreciated the caregiver. She said she never wanted to ask her daughters to clean the cat litter box, but she doesn’t feel bad asking someone who is getting paid.

In-home care costs less than living in an assisted living center, if it’s used the way Palmer uses it — a handful of hours a week while living in an affordable housing complex.

In-home assistance that does not include medical care costs a median hourly rate of $19, according to a 2010 cost-of-care survey by Genworth Financial, a global financial security company. Home Instead charges a little more than $20 an hour for personal care that includes anything more personal, such as bathing.

Assisted living facilities cost a median monthly rate of $3,185, according to Genworth Financial. This is the price tag that Palmer’s daughters expect when they eventually move their mother into an assisted living center for around-the-clock care.

A growing dilemma

Americans are entering an era when enormous numbers of adults will be facing decisions about the care of their aging and ailing parents. There are expected to be 63 million seniors by 2025, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. And, for the first time in history, more people are over the age of 65 than under 5 in the country.

“Baby boomers are retiring,” said Todd Sensenbach, owner of the local Home Instead franchise. “Over the next 20 years they’ll be aging. There’s a huge challenge ahead for all their children.”

Sharing the job

of caring

Sensenbach said in most families with an ailing parent, there’s a primary caregiver — and it’s typically the oldest daughter. Sensenbach calls this typical, hypothetical woman “Cathy.” The advice offered through the 50-50 program is aimed at Cathy.

In many families, it’s common for an adult son not to want to help with his mother’s personal care, Sensenbach said. But he might be happy to mow the yard or grocery shop. The 50-50 program helps Cathy define what needs to be done and learn how to communicate with siblings about helping.

Typically, adult children are not all geographically convenient. But remote adult children can help pay bills online, or just call regularly to check in and chat.

“Making decisions together, dividing the workload, and teamwork are the keys to overcoming family conflict,” said Sensenbach.

In Palmer’s family, the “Cathy,” as predicted, is the oldest daughter, Weatherson. But unlike the typical family in which siblings are remote or less helpful, her sisters are right there and very involved. Weatherson said at times she does feel overwhelmed, but she’s not resentful toward her sisters. Weatherson said she’s always been the caregiver in the family, so it seemed natural for her to fall into that role. It’s her personality type, she’s the oldest, and she has training as a nurse’s aide and an EMT. She’s retired, unlike both of her sisters.

And, just as the 50-50 program prescribes, they have divided the tasks involved with caring for their mother. Weatherson takes her on regular lunch, quilting and shopping dates. She also drives her to some of her doctors’ appointments.

Peterson takes her mother on a regular lunch date and manages her medical care, taking her to the primary physician appointments and overseeing all her medications.

Crawford has taken over the mail, bills, weekend visits and church outings.

“We all zoomed in on the things we do best for ourselves,” Crawford said.

There’s one thing in the 50-50 plan that they haven’t done yet: funeral arrangements. “We’ve talked about it,” Weatherson said. “We just haven’t done it.”

Planning for

the inevitable

Local author and counselor Ali Davidson advises families to have tough conversations early on, so the parent makes his or her own plans. These are hard conversations to have, and most people feel too busy or just don’t want to, Davidson said.

Adult children need to ask their parents questions such as: When are you going to know it’s time to stop driving? And, What’s the criteria for taking away your keys? Or: What happens when you don’t remember to pay your bills? Who will handle your money? Or: Where are you going to live?

These are just some of the issues that adult children could discuss with their parents long before the parent loses his or her ability to answer thoughtfully, Davidson said.

Then, “Put it on paper and sign it,” Davidson said. “Now there’s a plan. When something happens, you take it and show them what they wanted. The senior retains their power. It was their plan. The adult child also has permission to implement the plan without feeling guilty.”

Caring for aging parents can pile guilt and stress on the adult child, but this method, she said, can alleviate that a bit by working out the details before anyone is in crisis mode.

“They still have the right to choose for themselves even if it’s not the choice the adult child would want,” she said. “Kids want to keep parents safe and alive. The senior is not as afraid of dying as they are of becoming a nobody.”

“We all know we’ll get older. Aging happens slowly,” Davidson said. “Seniors can live with the aches and pains and diseases. It’s harder on the adult children. We are dealing with the upcoming loss of them, and our own aging.”

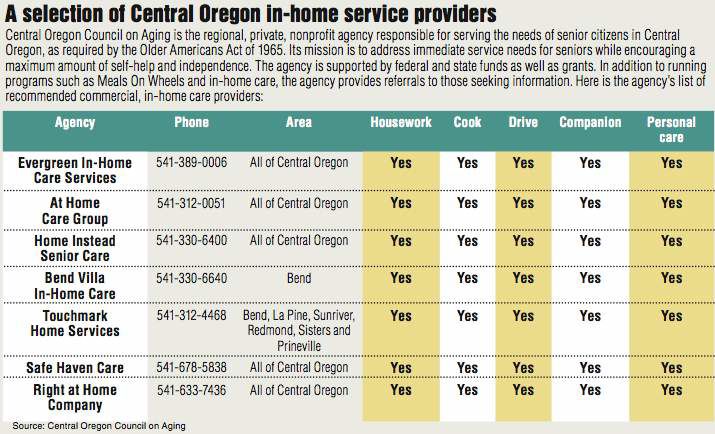

A selection of Central Oregon in-home service providers

Central Oregon Council on Aging is the regional, private, nonprofit agency responsible for serving the needs of senior citizens in Central Oregon, as required by the Older Americans Act of 1965. Its mission is to address immediate service needs for seniors while encouraging a maximum amount of self-help and independence. The agency is supported by federal and state funds as well as grants. In addition to running programs such as Meals On Wheels and in-home care, the agency provides referrals to those seeking information. Here is the agency’s list of recommended commercial, in-home care providers:

Evergreen In-Home Care Services 541-389-0006

All of Central Oregon

At Home Care Group

541-312-0051

All of Central Oregon

Home Instead Senior Care

541-330-6400

All of Central Oregon

Bend Villa In-Home Care

541-330-6640

Bend

Touchmark Home Services

541-312-4468

Bend, La Pine, Sunriver, Redmond, Sisters and Prineville

Safe Haven Care

541-678-5838

All of Central Oregon

Right at Home Company

541-633-7436

All of Central Oregon

Source: Central Oregon Council on Aging

Jennifer Montgomery / The Bulletin