Inventor of super glue dies

Published 5:00 am Monday, March 28, 2011

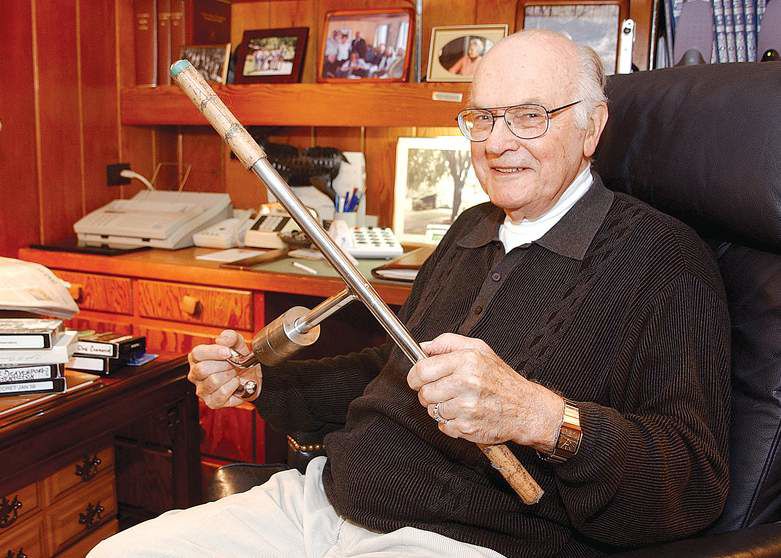

- Harry Wesley Coover Jr,, the inventor of cyanoacrylate glue, commonly known as Super Glue, sits in his Kingsport, Tenn., home in 2004. Coover died Saturday at the age of 94.

Harry Wesley Coover Jr., the man who invented Super Glue, died Saturday night at his home in Kingsport, Tenn. He was 94.

The cause was congestive heart failure, his daughter, Dr. Melinda Coover Paul, said.

Coover first happened upon the super-sticky adhesive — more formally known as cyanoacrylates — by accident when he was experimenting with acrylates for use in clear plastic gun-sights during World War II. He gave up because they stuck to everything they touched.

In 1951, a researcher named Fred Joyner, who was working with Coover at Eastman Kodak’s laboratory in Tennessee, was testing hundreds of compounds looking for a heat-resistant coating for jet cockpits. When Joyner spread the 910th compound on the list between two lenses on a refractometer to take a reading on the velocity of light through it, he discovered he could not separate the lenses. His initial reaction was panic at the loss of the expensive lab equipment. “He ruined the machine,” Paul said of the refractometer. “Back in the ’50s, they cost like $3,000, which was huge.”

But Coover saw an opportunity. Seven years later, the first incarnation of Super Glue, called Eastman 910, hit the market.

In the name of science, Joyner was not punished for destroying the equipment, Paul said.

Not long after, Coover made an appearance on the television show “I’ve Got a Secret,” which starred Garry Moore as the host. Coover’s secret was that he had invented Super Glue, and he was asked to demonstrate what it could do.

A metal bar was lowered onto the stage, and Coover used a dab of the glue to connect two metal parts together. Then, his daughter said, he grabbed hold of one and was raised in the air on the strength of his invention.

“Then Garry Moore jumped on, too!” she said. “And this is live television. But it worked. It absolutely worked.”

Nonetheless, Kodak was never able to capitalize commercially on Coover’s discovery. It sold the business to National Starch in 1980.

Coover was born in Newark, Del., on March 6, 1917. He studied chemistry at Hobart College in New York state and then received a master’s degree and a Ph.D. in chemistry from Cornell University. He worked at the Eastman Kodak Co. until he retired and then worked as a consultant. In 2004, he was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Last year, President Barack Obama awarded him the National Medal of Technology and Innovation. Coover was in the hospital, his daughter said, but his family made sure he was able to get to Washington for the award.

“That took a long time to percolate through,” Paul said. “So it was really nice that it came.”

Coover held 460 patents by the end of his life. Nonetheless, Paul said, he didn’t mind being known by his “most outstanding” invention.

“I think he got a kick out of being Mr. Super Glue,” she said. “Who doesn’t love Super Glue?”

One of his proudest accomplishments, Paul added, was that his invention was used to treat injured soldiers during the Vietnam War. Medics, she said, carried bottles of Super Glue in spray form to stop bleeding.

Besides his daughter, Coover is survived by two sons, Harry III and Stephen, and four grandchildren. His wife of more than 60 years, Muriel Zumbach Coover, died in 2005.

Super Glue did not make Coover rich. It did not become a commercial success until the patents had expired, his son-in-law, Dr. Vincent E. Paul, said. “He did very, very well in his career,” Paul said, “but he did not glean the royalties from Super Glue that you might think.”